When forensic archaeologist Scott Warnasch started digging at the future site of Newark’s Prudential Center in 2005, he was prepared to find skeletal remains. What he didn’t expect were two 19th century cast-iron coffins—or the 150-year-old mummies they contained.

Before it was home to the New Jersey Devils, a portion of the land where the arena now sits was home to something else: a 400-space parking lot. And long before the automobile was invented, the lot was a cemetery belonging to the First Presbyterian Church. More than 2,000 descendants of the founding families of Newark were buried there.

Prior to the archaeological dig—required before construction could begin—Warnasch and his colleague, Michael Audin, mined historical records and maps to determine the scope of their project on the 2.2-acre lot. They knew that some of the graves were moved in 1959 when the parking lot was built.

“I was sure it wasn’t a matter of if, but how many bodies were left,” says Warnasch. Once the dig began, a team of archaeologists quickly discovered a majority of the graves had been left behind and paved over.

It’s not uncommon to find human remains during construction projects in cities. Old, small cemeteries have often been built over without the graves being relocated. In the past year, additional remains have been unearthed in Newark, as well as in Philadelphia and San Francisco. But cast-iron coffins, used only briefly in the mid-1800s, are not an everyday discovery.

Audin remembers the moment Warnasch called him from the site with some unusual news. “I found what looks like pipe in the middle of the cemetery,” Warnasch had said. “I’m not sure what it’s doing here.” Audin told Warnasch to have someone excavate it and suggested they look at it together the next day.

“When I got there the next morning, they had already started excavating and, lo and behold, it was a cast-iron coffin. We both were like ‘Huh!’” says Audin.

Then they found a second one. “When we found them, I didn’t know they existed as burial receptacles,” says Warnasch, “and I didn’t know what to do with them.” For guidance, he called the Smithsonian Institute. As luck would have it, experts there had recently opened a newly uncovered iron coffin.

Should the coffins be opened and any contents cremated, like the rest of the remains found in the cemetery? Or should the possible remains be studied before being relocated? Without knowing the identity of the dead, who has the rights to the coffins?

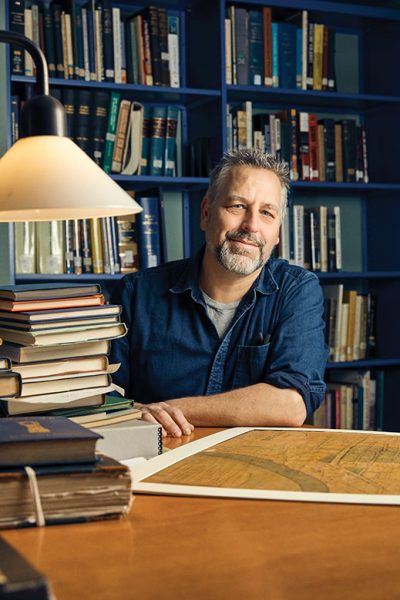

Much of what Warnasch, 50, has worked on during his 25 years as an archaeologist has involved cemeteries, which is to say, he’s used to asking these kinds of questions. In the case of the Newark mummies, he pushed for the opportunity to study them. The Smithsonian agreed and also wanted to be part of the process.

Warnasch grew up in Pequannock, attended high school in Wayne and studied anthropology at William Paterson University. He moved to California to complete field-school training, where he worked on prehistoric and historical cemeteries, before returning to New Jersey and settling in Bloomfield in 1997.

During the time he was working on the Newark cemetery project, Warnasch was also directing excavations of victims’ remains as part of the World Trade Center recovery. From 2005 to 2015, he worked for the New York City Office of Chief Medical Examiner’s (OCME) Forensic Anthropology Unit, where he was the senior anthropologist of the OCME’s World Trade Center operations.

The job had a great impact on him. “After the World Trade Center experience, I’m not interested in looking for arrowheads in cornfields anymore,” he says.

As he waited for the green light from interested parties to open the iron coffins and study the bodies inside—which would end up taking four years—Warnasch started chipping away at the mystery of the Newark mummies. He researched the coffins and tried to identify who exactly he could expect to find inside them.

The first clue was obvious. Wooden caskets usually rot or decompose in the ground, leaving only bones behind. Aside from rusted exteriors, these iron coffins looked much like they did on the day they were buried. One had a nameplate that read: “Capt. William A. Pollard. Died Sept. 5, 1854. 38 yrs/6 mos/22 days.” The other coffin was missing a nameplate, and without opening it, Warnasch had few ways of identifying the body it contained. He followed the trails he could, researching the history of the cast-iron coffins and Newark’s founding families at places like the New Jersey Historical Society, as well as the Newark library.

The style of iron coffins found in Newark, which Warnasch identified as Fisk Metallic Burial Cases, dates back to 1848. The coffins were fashioned after an Egyptian sarcophagus. Manufactured in Queens until around 1854, the airtight cases predate modern embalming practice, and were designed to preserve the corpse inside, whether for transporting bodies home to family cemetery plots or containing airborne diseases. They were expensive and generally used by wealthy people, unless the person inside had died from a contagious disease.

“A lot of my research suggests these iron coffins were used for practical reasons during times of need as much as they were for status and symbol,” says Warnasch.

He believes Pollard was buried in a Fisk iron coffin because he carried a disease, most likely cholera. Born in Newark in 1816, Pollard moved to Jersey City with his wife around 1841, where he was a member of the night watch and a lamp-lighter. “He was a golden son of Newark,” says Warnasch, “but his main career was in Jersey City.” Pollard went on to become the chief engineer of the Jersey City Fire Department, and later, deputy sheriff of Hudson County. His name regularly appeared in newspaper stories on both sides of the Hudson, says Warnasch, and his well-attended funeral was also chronicled in print. “The iron coffin was to quarantine his body,” says Warnasch.

In 2009, Newark’s iron coffins were finally opened at the Smithsonian, where a team of experts analyzed the remains. Having been sealed off from air, the two bodies were mummified, but had begun to decay since first being unearthed. (Neither Warnasch nor the Smithsonian had control over the coffins while they were in storage, awaiting their fate.)

Finally, Warnasch was able to confirm the identity of the second body. Based on the estimated age of the remains at death and headstone inscriptions near the grave where the coffin was found, Warnasch identified the mummy as Mary Camp Roberts. As he examined her small body at the Smithsonian, he found she had been interred in a burial shroud, wearing hairpins and a lace bonnet, with her hair braided and styled in Princess Leia-like buns. The stem of a flower was pinned to the shroud. She still had soft tissue under her clothing. “You could see her stockings were still full of body,” says Warnasch, referring to the corpse’s flesh. “They were like soapy sausages.”

There is less biographical information about women from the period, but Warnasch was still able to reconstruct details about Roberts’s life using clues from inside her coffin and historical records. She was born around 1764 as Mary Camp in Camptown (now Irvington), which was named after her family, and was a descendant of the original Connecticut colonists who settled Newark in 1666. She married Moses Roberts, also a descendant of one of Newark’s founding families. They moved to a home on Clinton Avenue in Newark around 1807. In 1852, she died of natural causes at the age of 88.

By studying these 150-year-old bodies, Warnasch was able to get a glimpse into what their lives were like in the era when Newark was a hub of the Industrial Revolution. Through analyses of the bones and teeth, he gained insight into their health and diets. Fabric and clothing in the coffins offered clues about the fashions of the time and the occupations these people might have held. The coffins themselves speak to a period during the Victorian era when people were reassessing their relationship with death.

“As far as I know, these are the only [cast-iron coffins] to have been found in New Jersey,” says Richard Veit, a New Jersey cemetery expert and professor of anthropology at Monmouth University. “They’re certainly rare and certainly interesting. They speak to a different era in history, and that’s why Scott’s work is important.”

Says Audin, “Everyone has their topic that really interests them. The cast-iron coffins just kind of struck it with Scott.”

Warnasch is now working on a book about Fisk cast-iron coffins, which will include biographies of the two mummies found in Newark, as well as one recovered in 2011 in Queens, a young African-American woman who died of smallpox.

In January, Warnasch teamed up with Joe Mullins, forensic artist for the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, to reconstruct Pollard’s facial features. Students enrolled in a facial-reconstruction seminar at the New York Academy of Art were given a 3D print of Pollard’s skull, which they used to fashion a clay sculpture of his face.

Now that he has a face to work with, Warnasch is examining historical photo archives for any taken of the Jersey City police and fire departments. He hopes to be able to identify Pollard in some of them.

“This is what gives me goosebumps about archaeology. I’ll pick up an artifact, whether it be from 10,000 years ago or 200 years ago, and think somebody else held this, too,” he says. “I can identify with them. I know what this feels like, and so did they. It’s the same thing with the bodies themselves.”

I have been buying old (Morgan) silver dollars. I have what folks 100-129 years ago used on a daily basis. I don’t know why. I just like it.

I find it historical yet very disturbing. Who are u to disturb. An open there coffins ? I know this sounds out of the way but is there no honor for the dead ? Who was to move them ? An why wasn’t it check on to see if all were moved an I am sure the person or persons were paid yes it’s history but have u check if any long family members still are alive . ? How would u feel if in a hundred or more years if your last place of rest was build upon payed over dug up ? U stated this is common why ? Again I ask is there no honor for the dead ?????what right do u are any one have in invading there bodies ? I understand but I first think or would

Ike to hear if u look into any family members still being alive can u fill me in on this ? Can u at lease try to find a family member . An ask permission I know this is not the first this is one of many.

THANK YOU!!!!!

Well-written article and congratulations to Scott Warnasch for taking the time and effort to learn about these unusual artifacts from the mid-19th century. So much of what has come before is thrown out, disregarded, ignored. But you took the opportunity to delve into a mysterious object and investigate it as fully as possible. We are all the richer for that effort. The fact that so many burial places have been treated as anything but sacred is a sad comment on our society; but your respect for the artifacts and the line of work to which you’ve dedicated your life speak to me of deep respect and a useful curiosity to understand what has come before… (and thank you for your work on the World Trade Center Recovery project over 10 years – that is true dedication)

Fascinating. Great work

Grave robber no matter how you look at it. If there are bodies buried there, that’s where they should stay. These jerks — they pave paradise and put up a parking lot — remember that song?

And… then what happened? Were the coffins reburied, with markers put up, since the identity of the occupants was known?