Photo by Colin Archer/ANJ.

You would expect a powerful man to have a powerful boat. But Stephen N. Adubato Sr. is happy with his 13-foot Hobie Cat.

“This is the kind of boat a teenager would have,” says the longtime Newark political boss. “I’m like a kid.”

Indeed, Adubato, who will turn 77 on December 24, moves effortlessly in hip-deep water as he slides the small craft into Barnegat Bay, just down the road from his weekend home on West Point Island in Lavallette. Once he’s far enough from shore, he springs with ease out of the water onto the flat deck of the Hobie Cat.

On this sunny day in early July, Adubato has two passengers. It’s not until they are a few hundred feet from shore that he confesses, “I’m a lousy sailor.”

These days, Adubato usually sails alone, enjoying rare moments of solitude in a life that has been all about family—his blood family and the family of Essex County political loyalists that he has built through four decades of arm-twisting and finger wagging. This is a man who has created institutions, made careers, and crushed others.

Adubato’s base of operations is the North Ward Center, a nonprofit social services organization he launched in 1970. The center, housed in a fortress-like nineteenth-century mansion on Mount Prospect Avenue in Newark, operates a pre-school, a job-training and language-training center, an adult medical day care center, youth recreation programs, and Adubato’s crown jewel, the Robert Treat Academy, an award-winning charter school.

Last year, Adubato relinquished his title as executive director of the North Ward Center, but make no mistake: He has not retired. In August, a second campus of the Robert Treat Academy opened in Newark’s Central Ward. Now Adubato is bent on creating a center for children with autism.

Although he has the résumé of a saint, Adubato is no angel. “I’m not a good person, not a kind person,” he frequently tells reporters. “I’m rough, very rough to everybody.” Adubato relishes being crude, flaunting foul language and outrageous statements. A conversation with him means being poked and prodded as he seeks your sensitive spots. In an interview, his answers are peppered with questions (“Do you understand anything I’m telling you?”). For emphasis, he swats aside this reporter’s notebook, commanding, “Look at me.”

Yet he also wants you to know there’s a pussycat inside. Adubato is wistful as he recounts his hard-knock childhood in a tenement on Factory Street in Newark’s old First Ward. His father was an educated man (he completed two years on a football scholarship at Bucknell University) who ran a gas station to eke out a living during the Depression. He moved up to a civil service job and later became director of the local Boys Club. Then, in 1950, Michael Adubato died of heart disease at 44, leaving his wife, Mildred, to raise five kids.

“It was the worst year of my life,” Adubato says. The man they call Big Steve chokes back tears as he recalls how his mother insisted that he fulfill his dream of going to college, although the family had no money for tuition.

Adubato earned a bachelor’s degree at Seton Hall (while working in a barrette factory), did a stint in the Army, and returned to Newark to start his teaching career. While teaching, he studied law at Rutgers but ultimately received a master’s degree in education from Seton Hall. Along the way, he married the former Fran Calvello of Newark. They have three children: Theresa, Michele, and Steve Jr., the broadcaster, author, former state legislator, and columnist for this magazine.

It was while teaching social studies at Broadway Junior High School in Newark that Adubato got the political bug. He and a group of other teachers decided to run in 1962 as Democratic district leaders. They all lost—except Adubato. “Not only did I win, I slam-dunked,” he claims. “I found out I was a natural.” Surrounding himself with hard workers (“animals like me”), he built an organization, and in 1968 his fellow Democrats elected him North Ward party chairman.

It was no simple feat. In July 1967, riots had swept through Newark. Italian, Jewish, and Irish families sought safety in the suburbs. Ever the contrarian, Adubato stayed put, gaining support among blacks and Hispanics and wresting control of the local party from longtime boss Anthony Imperiale.

Feeling empowered, Adubato made the bold move in 1970 of supporting an African-American candidate, Kenneth Gibson, for mayor. Incumbent Hugh Addonizio played the race card, stoking the fears of Newark’s remaining white voters. Addonizio’s supporters portrayed Adubato as a traitor to his own people. “I loved it!” Adubato declares. Fran Adubato’s memories are less pleasant. “It was a very dangerous time,” she says. “Physically dangerous. I feared for the kids. I feared for Steve.”

What started out as a calculated risk proved to be a stroke of political genius. Gibson won, giving Adubato an important ally for the social projects that would solidify his hold on the North Ward. “Gibson helped me with the North Ward Center, but not politically,” says Adubato. “Politically, the blacks were very confused by me, and I don’t blame them.”

Adubato’s attitude toward African-Americans and Hispanics—and pretty much every ethnic and racial group—is indeed confounding. He defies political correctness, assigning broad stereotypes based on ethnic origins. Yet he invokes the words of Martin Luther King Jr. by insisting that individuals be judged on the content of their character. And he believes that minorities respect him because he speaks his mind.

“Nobody can talk to blacks publicly like I can,” he says. “Most whites only say what they think is acceptable. They don’t say what’s in their heart. I do.”

Newark Mayor Cory Booker has plenty of firsthand experience with Adubato’s racial rhetoric. “Anybody who sits across from Steve knows his biases are equally applied to all, from Italians, to Polish, to blacks, to Latinos,” says Booker. “That’s what’s redeeming about him.”

Adubato supported Booker in his 2006 campaign for mayor, but the two men have backed opposing candidates in other Newark elections. Earlier this year, they mended fences. “I’ve told Steve he’s got the best trump card for me, because I would never hurt his institutions,” says Booker. “I believe in what they do and I support what they are accomplishing.”

Key among those institutions is the Robert Treat Academy. Started by Adubato in 1997, it was in the first group of charter schools approved by the state. Universally recognized as a model for urban education—it was named a Blue Ribbon School in 2008 by the U.S. Department of Education—Robert Treat Academy serves about 450 students in grades K–8; 78 percent are Latino and 18 percent are African-American. According to a spokesman, members of its 2009 graduating class were offered $3.1 million in scholarships and were recruited by such prestigious private high schools as the Lawrenceville School in Lawrenceville, Delbarton School in Morristown, Seton Hall Prep in West Orange, St. Benedict’s Prep in Newark, and Immaculate Conception in Montclair, as well as numerous out-of-state boarding schools.

A tour with principal (and Newark native) Michael Pallante through the Robert Treat Academy’s sparkling clean, modern facility—opened in 2001—is a revelation. Uniformed students excuse themselves as they pass in the halls; in the classrooms, hands fly up as a teacher asks for participation. The students’ test scores are the highest of any K–8 school in Essex County. These are inner-city kids who have learned how to learn.

Adubato sees the achievement in broad social terms. His mantra: “Urban education creates tax burdens. We create taxpayers.”

He decries what he calls the urban minority experience. “Can you imagine, generation after generation never pay taxes but take a tremendous amount of taxes from people who work hard,” he says. “That’s a terrible thing. It’s horrible for the individual and horrible for society.”

As of 2008, the North Ward Center had an annual operating budget of more than $16.7 million (excluding Robert Treat Academy, which has a separate budget). Almost half the budget goes toward salaries for the center’s 220 employees—including Adubato, who still collects the same annual salary of $115,000 he earned as executive director. His key role is fundraising. The center’s 2007 financial report indicates grants and contributions from government and private sources of $16.5 million. (Donations in 2009 included a $500,000 grant from Oprah Winfrey’s foundation.)

The success of Adubato’s social institutions is directly linked to the strength of his political organization. Adubato can mobilize large groups of volunteers from within his community to work for the candidates of his choice—in Newark and throughout Essex County. Once elected, those politicians can help provide the government support needed for the North Ward Center’s programs.

Does he play politics to fuel his social institutions, or are the social institutions merely the engines that feed his undisguised taste for power? For the estimated 8,300 individuals who benefit from the North Ward Center’s services, it hardly matters. For his part, Adubato is unapologetic about playing tough and using politics as a means to an end.

“There shouldn’t be political bosses,” he declares. “You should not have to use politics to get programs. Listen to me, I’m guilty.” Then again, he says, if we allow giant corporate lobbies to influence government, why should we be suspicious of an organization that lobbies for social services for its own community? “If I didn’t do it, these people wouldn’t get the help,” he declares.

North Ward Councilman Anibal Ramos confirms that Adubato’s appeal lies in the strength of his community institutions. “Any program that he gets behind succeeds,” says Ramos, a former political foe and current ally. “People look at what the outcomes are. They look at what he’s helped to build. That gives him a whole lot of credibility.”

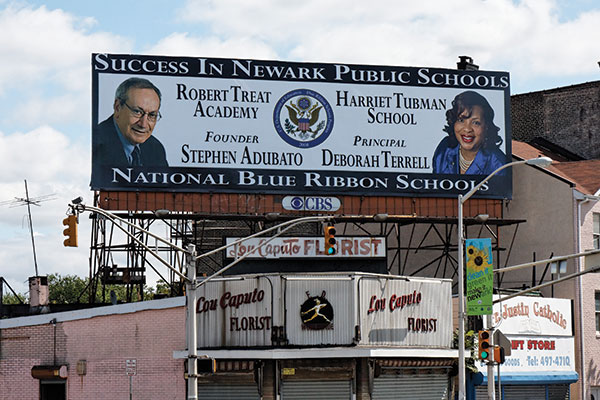

Adubato and his Robert Treat Academy share this billboard on Bloomfield Avenue in Newark with his friend Deborah Terrell, principal of the Harriet Tubman School. It’s one of several Newark billboards touting the success of Adubato’s community initiatives. Photo by Eric Levin

Adds Booker, “Steve is not going to win a popularity contest, but I think he has the allegiance of people because he runs the center that takes incredibly good care of your grandmother, because he runs the day care that people are trying hard to get into, because he runs the charter school that is the highest performing charter school in Essex County. It’s very clear to folks that here is a guy who has brought such substantive institutions into the neighborhood that if it comes to an election, I’m going to support the guy that has been supporting my family and me.”

Still, this is New Jersey, and in New Jersey power seems synonymous with corruption. Adubato rejects any notion that he has abused his power. “Everyone is afraid of power—and they should be,” he says. “They don’t believe that someone with political power can do the right thing. But look at me. I do the right thing with power.”

What’s more, he says, he insists on honesty from all around him. “If you do anything criminal, anything wrong, I’m going to be the first person to testify against you,” he says. “Why? If you build an organization and you cheat, you’re threatening all the work. It’s not just about morality, not about honesty. It’s practical.”

Those around him include family members and longtime supporters. When Adubato stepped aside last year as executive director, his daughter Michele left the N.J. Regional Day School, where she served as vice principal, to become deputy executive director of the North Ward Center. (Adrianne Davis, a cofounder of the North Ward Center and a former Essex County freeholder, was named executive director.) Michele’s older sister, Theresa, serves as vice principal of the Robert Treat Academy. And Fran Adubato also has a salaried post, as head of the senior citizens’ program.

Nepotism? Perhaps, but there is no denying the credentials or the sincerity of these individuals. In fact, Michele, whose previous school served kids with developmental disabilities, is the driving force behind the ambitious autism project. She envisions a “one-stop location” to provide educational and adult services for under-served autism families in Newark.

Throughout Essex County, one can find Adubato protégés in power. County executive Joseph N. DiVincenzo Jr. is a former North Ward Center staff member; Adubato refers to him as a second son.

Carmine Casciano, the county’s superintendent of elections, was a student in Adubato’s seventh-grade history class. Now married to an Adubato cousin, Casciano also serves on the board of the North Ward Center. Another protégé is Teresa Ruiz, a one-time pre-K teacher at the North Ward Center who was elected to the state Senate in 2007 with Adubato’s support. Ruiz is also cochair of the Hispanic Scholarship Program for the North Ward Center.

But Adubato’s real might is seen in his ability to attract the state’s power elite. His annual mid-March dinner is a must-attend for Jersey politicians of both parties. And when DiVincenzo recently dedicated a corner of Newark’s Branch Brook Park as the Stephen N. Adubato Sr. Sports Complex, Governor Jon Corzine and Senate President Richard Codey felt compelled to attend and speak Adubato’s praises.

Challenge Adubato and you will feel his political clout. Among one-time allies who have learned the hard way are former North Ward councilman Hector Corchado and former state Assemblyman Wilfredo Caraballo—both of whom lost elections after losing Adubato’s support.

For all his bluster, Adubato leads a simple life. Married 55 years, he and Fran have been living for 34 years in a house that they rent from the North Ward Center. They bought their first weekend home at the Jersey Shore 37 years ago and have traded up several times to their current place, a modest, three-bedroom home in a quiet community a few blocks from Barnegat Bay. Adubato says they paid $300,000 for the home in 1995.

After our morning sail, we continue the interview drinking iced tea in the Adubatos’ yard. There’s a small pool, and in the corner stands a playhouse for the youngest of Fran and Steve’s five grandchildren.

Here Adubato grows introspective, talking about regrets (“As a young man, I put ambition before my family”) and hopes for the future. He confesses that he has cut back his workload (“I’m old, I can’t help it”) but looks ahead to what he calls “the biggest project of my life.” That would be the autism center, projected for a September 2011 opening. “It would be such a satisfaction to help those people,” he says. “Those families. You know how they suffer?”

Can he create yet another successful social institution for Newark? Hard work is all it takes, he says, concluding: “That’s the genius of Adubato.”