A century ago this month, New Jersey’s only major league baseball franchise debuted. In 1914, the newly formed Federal League had declared itself a rival to the National and American leagues, with hopes of assembling teams that could compete at the same elite level. A year later, oil tycoon Harry F. Sinclair moved one of the Federal League teams, the Indianapolis Hoosiers, to Newark, renaming them the Peppers. The Hoosiers had won the 1914 Federal League pennant, so Sinclair thought his Peppers could draw fans from New York’s three pro teams, the Yankees, Dodgers and Giants. That might force the established leagues to seek peace with the Federal League, which had raided their rosters for talent.

The Peppers played in the new, $100,000, 20,000-seat Harrison Park, just across the Passaic River from where NJPAC now stands. When Giants manager John McGraw rejected a $100,000 offer to pilot the team, Bill Phillips, who had managed the Hoosiers, stayed on the job. The Peppers opened in Baltimore, where they won three against the Terrapins, then lost two to the Brooklyn Tip-Tops before their April 16 home opener. Before an overflow crowd, Newark Mayor Thomas Lynch Raymond threw out the ceremonial first pitch. The Peppers lost to Baltimore, 6-2.

Matters didn’t turn out the way Sinclair had hoped. On the field, the team was shaky, and in June, second baseman Bill McKechnie, who went on to a Hall of Fame managerial career, replaced Phillips at the helm. The Peppers didn’t set the world afire at the gate either. Sinclair tried to boost attendance with bicycle races, threatened to move the club unless the local trolley line was extended to his park, and experimented with reducing prices—to as low as 10 cents in the bleachers. The club ended in fifth place in the eight-team league, with an 80-72 record, six games behind the first-place St. Louis Terriers.

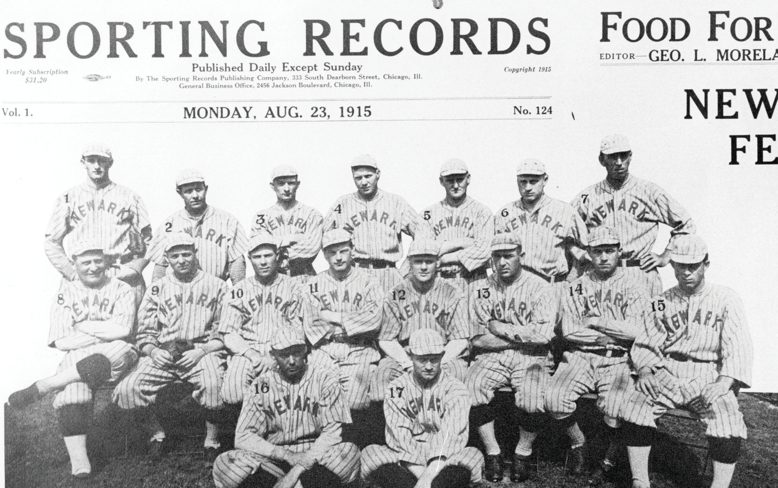

The Peppers’ best hitter was right fielder Vin Campbell (who batted .310), followed by center fielder and future Hall of Famer Edd Roush (.298). Perhaps their most popular player was the clownish, 38-year-old utility man Germany Schaefer, recruited from the Washington Senators more for his entertainment value than for his .214 average. The team may not have hit much, but their pitching staff was the best in the league, with a 2.60 earned-run average. The anchor was right-hander Ed Reulbach (21-10, 2.23 ERA), whom the Dodgers had cut for his efforts to organize players into a protective association.

Sinclair was central to settling the interleague war. Threatening to move the franchise to New York for 1916 even though the Federal League was collapsing financially, he emerged from the peace negotiations with a profit, gaining a direct $100,000 buyout over 10 years and control of most of his player contracts, which he sold to teams in the established leagues. Then he returned to the oil business, where profits were more readily available.

But his story didn’t end there. In 1927, Sinclair was charged with bribing Interior Secretary Albert B. Fall to secure government oil leases in the Teapot Dome Scandal. His case ended in a mistrial because he had the jurors followed, for which he was found guilty of contempt of court and served six months in jail.

Nor did the Peppers’ story end with the 1915 season. Even after Sinclair had abandoned the cause and the new league folded, backup first baseman Rupert Mills insisted on honoring his contract. Refusing a $600 buyout of the $3,000 owed him for the 1916 season, he agreed to work out every day for seven hours. So for 65 days, until he left in July to play for Harrisburg in the New York State League, Mills showed up at Harrison Park, making him the only Federal League player in 1916. As for Harrison Park, it burned to the ground in 1923.

Nick Acocella is the editor and publisher of Politifax New Jersey. He lives in Hoboken.