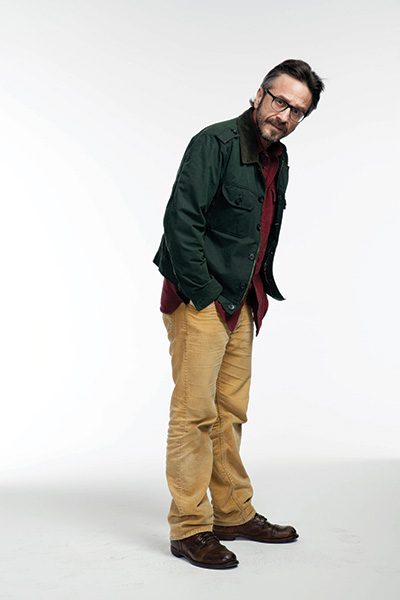

“You’re like a therapist!” marveled singer/songwriter Lucinda Williams during her interview with comedian Marc Maron. Actor Michael Keaton told him, “You’re so great at this.” “This” is WTF, the podcast Maron, now 49, launched out of sheer desperation in 2009 after his second excruciating divorce and the collapse of his stand-up career. Seeking some sense of community, he began recording conversations in his Los Angeles garage with artists he admired, especially his fellow comics. These startlingly frank, funny and fascinating encounters (at wtfpod.com) now number more than 400 and range from Louis C.K., Mel Brooks, Richard Lewis and Sarah Silverman to rockers John Fogerty and Billy Bragg (Maron is an avid guitarist) and actors like Mad Men’s Jon Hamm. A student of comedy history and technique, Maron can also question sharply when questions of ethics arise (see Jay Mohr, Carlos Mencia). Deemed by the New York Times “a cult hit and a must-listen in show business and comedy circles,” WTF (which stands for what you think it stands for), revived Maron’s stand-up career and led to the publication in May of his raucous and affecting memoir, Attempting Normal, and the debut of his IFC TV series, Maron, in which he plays a stressed-out comic whose podcast gives his life a tentative toehold on sanity.

New Jersey Monthly: Before your family moved to Albuquerque, you spent your first six years in Wayne. How Jersey do you feel?

Marc Maron: I do feel attached to the place. My grandfather owned a hardware store in Haskell. It smelled like oil and metal, had big bins of screws, and I used to hang out with these old guys who stood around talking about fixing [stuff]. Both my parents are from New Jersey. My father was valedictorian of Snyder High School [in Jersey City]. I had one set of grandparents in Pompton Lakes and another set in Bayonne and later Asbury Park. I had cousins in Oakhurst and a great aunt who lived in the Horizon House high-rise in Fort Lee, where you could look right across the river to New York. My mother was very connected to the museums and stuff in New York, so the proximity to the city very much helped define me. I spent time in New Jersey maybe three times a year right through college. After that people started to drift to Florida and other places.

NJM: What are some of your childhood memories?

MM: Having milk delivered, going with my grandmother to buy smoked fish. There was always something about driving in the summer—that weird humid haze to everything. We’d drive past Secaucus on Route 3 and my grandmother would say, “That smell is because there used to be pig farms there.” There was a Nabisco factory somewhere, and she’d ask me if I could smell the cookies. When Paramus Park mall was built, we were all very excited. I remember it as having the first food court. My grandmother took me there and said, “That’s food from all over the world!” The idea of that, it was like being in an amusement park. I had a gyro for the first time. I thought that was amazing—a Greek sandwich!

NJM: When you hit rock bottom, how did you decide to do a podcast?

MM: I just wanted to keep doing something. I couldn’t get bookings. I knew people were doing podcasts, so I just figured it out. It took awhile [to catch on], but there were some breakthrough interviews—Zach Galifianakis, Robin Williams, Carlos Mencia, Judd Apatow, Gallagher—that generated a kind of excitement. But I never had a plan. I never expected anything from it.

NJM: In Attempting Normal, you write about trying to find a place for yourself. Was stand-up comedy always that place?

MM: I always felt it was a bunch of misfits. Very few people live that kind of life, and coming up in New York and Boston, it was always my community. We were just a bunch of kids trying to figure out how to do this. I didn’t know how I would fit into my own skin, or into other people’s perceptions, but I always knew comedy was it.

NJM: Many comedians you interview have parents who divorced when they were young, yours included. Many come from dysfunctional families. You describe your own family that way. It almost seems like comedy is a way to redeem one’s life.

MM: Yeah, well, comedy is a great gift. You can make things easier to understand, you can disarm things, you can be defensive, you can enlighten and elevate. I don’t know if there is a redemption story for everyone who does it. I’m sure there are plenty of miserable people in my business who don’t see it that way. But for me, when everything else goes awry, I know I can get on a stage and entertain a room full of strangers. And I think that’s a very noble undertaking. It’s who I am in my heart and my bones. So in that way, knowing that I always have comedy is redemptive, yes.

NJM: You’ve described your father, a retired surgeon, as bipolar as well as remote. In the book you say you enter the little you know about his early life into your “emotional abacus” and “mov[e] the beads around trying to figure out who I am.” How has he responded?

MM: It’s tricky. My father is still around, he’ll be 76 this year, and he’s pretty angry about the book. You know, I love the guy, but he’s got problems. What are you going to do? I don’t know how much he reflects on it, and I don’t know how much he sees his own issues with clarity, but he’s still fighting the good fight—against what I’m not sure.

NJM: You kicked drugs and alcohol in 1999, but when you talk about your haywire years, you often sound nostalgic for what sounds like a golden age. Has stand-up itself changed?

MM: No, there are still guys hanging around with notebooks in the back of half-empty rooms, eating late, sleeping late, walking around thinking. In that sense it hasn’t changed. There does seem to be more comedy than ever and more options for people to find their way with their talent. But it still seems that the people who really have it will rise up and shine somehow, and there will always be people just chipping away and getting by.

NJM: So no nostalgia?

MM: It was a little easier to define one’s success when the industry was more intimate. There was a set of hoops you had to jump through when there was just three or four TV networks. Everybody was fighting for the same prize. It’s sort of blown out now. Some of the integrity of what it means to be a comic has been a bit watered down. If there is anything to be nostalgic for, it’s the specific trajectory of the comedy career then. I’m not saying it’s bad that’s gone. But it’s definitely different.