When Plainfield police Lieutenant Ronald Lattimore started his day on the morning of March 23, 2011, there was no reason to imagine he had anything but a long and productive life ahead of him. Lattimore, 52, was a 26-year veteran of the force, newly eligible for retirement. By all accounts, he and his wife, Bobbi Boges, had been committed to each other for more than two decades. He came from a large and respected Plainfield family: His late father, the Reverend Ovie Lattimore, founded Plainfield’s Rose of Sharon Community Church; his brother, Everett, who died in 1991, was Plainfield’s first African-American mayor. One of 16 siblings, Ronald Lattimore, say friends and family, was funny and fun loving, generous and community minded. His brother Michael Lattimore, police chief and director of the department of public safety on the Newark campus of Rutgers University, describes him as “the glue in the family.”

But on the evening of March 23, the man who meant so much to so many people made a decision that shattered his family and bewildered almost everyone who knew him. That night, Boges opened the door to the garage at the couple’s Watchung home and found her husband dead of a self-inflicted gunshot wound. More than a year later, she says, “I can’t shake that vision out of my head.”

As news of Lattimore’s death circulated through Watchung, colleagues, friends and family responded with disbelief. “It was stunning, to be honest,” says Lattimore.

To this day, no one is sure what curtain of darkness descended on Ronald Lattimore over the course of that unseasonably cold March afternoon. Like so many survivors of suicide, the family is left with questions and regrets. “I often think,” says Michael, “that had someone come five minutes before he took his life, it wouldn’t have happened.” Meanwhile, Boges is still plagued by the feeling that “as his wife and best friend, I should have been able to read his mind.” That she has a master’s degree in psychology and a doctorate in medical humanities, she says, only compounds the guilt.

Boges has found some solace in the support she’s received from others in the law enforcement community who have also lost a spouse to suicide—and in New Jersey, their numbers are considerable. While the state’s general suicide rate is one of the lowest in the nation—6.2 in 100,000—the rate for police officers here is 15.1, as reported in 2009 in the New Jersey Police Suicide Task Force Report. Between 2010 and 2011, nine New Jersey law enforcement officers died in the line of duty, but 23 took their own lives.

According to data for 2008 reported in the International Journal of Emergency Mental Health, New Jersey (and New York) trailed only California in the number of police suicides that year.

The suicide rate is even higher among the state’s corrections officers—34.8 in 100,000—which Kenneth Burkert, a corrections officer in Union County and a Policemen’s Benevolent Association state delegate, who lost two colleagues to suicide, ascribes to “the isolation of never being allowed out of the jail during an 8- to 16-hour shift and having to deal with the dark side, with individuals who can’t survive by society’s rules.”

Eugene Stefanelli, a crisis counselor for the New Jersey State PBA, says the number of police suicides amount to an epidemic. He speculates that primary factors that lead to suicide include dealing with the judicial system, operating in high-crime areas and officers’ personal life crises. In fact, statistics from 2002 to 2011 indicate that suicides from departments in high-crime areas represent roughly a third of all suicides among municipal forces.

Stefanelli has worked with cops for nearly two decades, which puts him in a unique position to understand the stress factors that make law enforcement officers particularly prone to suicide. “The primary problem that police officers suffer from is cumulative stress,” says Stefanelli. “The pressures build over time, and then there’s that one incident that can push them over the top.” Anthony Wieners, president of the New Jersey State PBA and a Belleville cop with 32 years on the job, is intimately acquainted with those pressures. “Within the first week of being on the job,” he says, “you change your sleeping habits, you change your eating habits”—he notes that police officers have a higher incidence of not only suicides but also of cancer and gastrointestinal disorders—“and you’re exposed to things that normal people never see. First day on the job, you can be involved in a shooting, you can see a child struck by a car or somebody hanging from a rope or a kid who’s overdosed on drugs. From the very first day we put on a uniform, our profession puts us in a different risk category.”

And then, says Wieners, there’s “the accessibility of the means to carry it out.” In other words, when you’ve got a gun with you on the job and in the house, it isn’t hard to back up suicidal thoughts with action. A culture of stoicism only increases the risk. “In police work,” says Michael Lattimore, who might be describing his late brother, “you have to put on a face when you’re out here working; you can’t show your emotions. If there’s something bothering us, we tend to mask it.” Officers in crisis who do want to reach out—to a partner, a superior, a therapist—often don’t, for fear of ending up on “the rubber gun squad”—cop-speak for losing your gun and possibly your job.

And what do you do if you’re at the halfway mark to retirement—which in New Jersey is usually 10 years—and you’re not sure you can take another decade? The stats hint at an answer. According to a 2009 study, also published in The International Journal of Emergency Mental Health, cops are at the highest risk of suicide when they’ve been on the job for 10 to 14 years. But retirees are also at increased risk. In 2005, Richard Kelly, a lieutenant on the Ewing police force, committed suicide four years after he retired. Like many officers of his generation, police work was more than a job for Kelly—it was the way he defined himself.

“It becomes very hard to find yourself if you don’t maintain other interests throughout your career,” says Kelly’s widow, Cathy. “And then, when you retire, you struggle with your identity, because the department has become your identity.”

Cathy Kelly is one of many in the state working to turn the numbers around. Two years after her husband’s death, she connected with the PBA, offering herself as a resource for law enforcement families struggling to find their way after a suicide. Providing peer support has been a kind of therapy for her and, she says, “a way to give purpose to my husband’s life.”

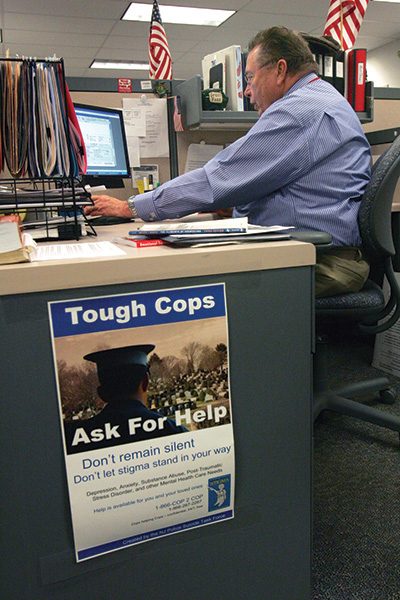

While police suicides were once a taboo subject for the state’s law enforcement community, there’s been a recent push among suicide prevention professionals to talk about them openly—and to honor the lives of officers who’ve killed themselves—as a way to help remove the stigma of suicide. At the Piscataway call center of Cop2Cop, the state’s peer-to-peer counseling program, there’s a gold-fringed banner on the wall behind the phone bank that looks like something you might carry in a small-town Memorial Day parade. The words “Cop2Cop” are stitched into the banner surrounded by a field of stars and badges, each badge representing a New Jersey law enforcement officer who took his or her own life.

Administered by the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, Cop2Cop was mandated by the state in 1998 after a rash of police suicides. The program—which is entirely confidential—employs retired law enforcement officers who man the 19 help lines around the clock and field calls from cops in crisis.

A more recent cluster of suicides in 2008 prompted Wieners to approach then-governor Jon Corzine with heightened concern. In response, Corzine formed a task force, composed of law enforcement and mental health professionals, to examine the problem of police suicide and suggest ways to ameliorate it. The resulting report recognized what many in the law enforcement community already knew: that “the stress of law enforcement work, as well as access to firearms puts officers at above-average risk for suicide.” The task force recommended, among other things, that the state provide more suicide awareness training to officers and supervisors, improve access to and increase the effectiveness of existing resources, and combat the reluctance of officers to seek help.

Paramount among those existing resources was Cop2Cop. On the task force’s recommendation, the Governor’s Council on Stigma funded a marketing campaign to get the word out about the program to the state’s law enforcement personnel.

As Cop2Cop has become more widely utilized, it has fine-tuned its definition of peer. “We now connect chiefs to chiefs, women to women, corrections officers to corrections officers, wounded officers to officers who’ve been wounded,” says Cherie Castellano, the program’s director, who is married to an officer and has published more than a dozen books about peer support in law enforcement. Cop2Cop, whose peer counselors address a gamut of issues from substance abuse, financial worries and relationship problems in addition to suicidal thoughts, has taken more than 30,000 calls over the past dozen years and claims to have averted 189 suicides out of 192 calls.

Pat Ciccone, who has been a peer counselor at Cop2Cop since its inception in 2000, offers a simple explanation for the program’s efficacy: “It’s the trust factor—cops would rather talk to cops than anybody else.” The fact that the counselors are retired officers allays callers’ fears that their confidentiality will be breached. In addition, says Castellano, by their own example, the peer counselors offer hope: “These guys draw on their life experiences—not just their suffering or their challenges, but their resilience and their strength. They’re modeling the fact that you’re not alone and you can get through this.”

Unfortunately, Cop2Cop can’t help the officers who don’t know it exists or are unwilling to call, which may explain why the state’s suicide numbers have not improved over the past decade in spite of the program’s existence. “We’ve looked at all the suicides that have taken place in our 12 years of operation,” Castellano says, “and out of the 78 officers who’ve killed themselves in that time, we’ve only spoken to three of them. That’s something we’re trying to change.” (Cop2Cop’s statistics—which are unique in including corrections officers and retired cops—show the annual number of suicides from 2002 to 2011 as 2, 10, 4, 1, 6, 0, 11, 13, 13 and 12.)

Cop2Cop also is expanding the concept of peer support. In 2004, the organization began training the state’s law enforcement officers in the suicide-prevention method known as QPR (Question, Persuade, Refer); some 5,000 New Jersey cops have received the training to date. Officers proficient in QPR watch their partners for signs that they might be in crisis and learn how to ask them if they’re feeling suicidal; if so, they persuade them to seek help, and refer them to mental health resources. In Union County, Cop2Cop has trained more than 700 officers so far, thanks in part to prosecutor Theodore J. Romankow, who was moved to implement the training as a result of his own exposure to police suicide. “After I started as prosecutor in 2002, there were a number of police suicides in Union County,” he says. He viewed one of the bodies and was deeply affected by the experience. When he learned about Cop2Cop and QPR from Kenneth Burkert, he signed on. He cites an increase in Cop2Cop calls from Union County as evidence that the training is working, and he’s trying to convince police chiefs around the state to offer it in their departments. “The major objection is lack of time for the training,” Romankow says. “They have to find the time.”

The governor’s task force also recommended that suicide prevention training be provided to all recruits as part of basic training, something that’s actually been accomplished under the auspices of Cop2Cop and the PBA. But Castellano notes that “it’s not the recruits who are killing themselves; it’s retirees and officers at the mid-point in their careers.” To that end, she’s been lobbying the state’s prosecutors and police chiefs to make the training available at the 10- or 15-year mark.

Bill Ussery, a retired officer and a licensed professional counselor, and one of the first people to man the Cop2Cop help line, has an even more radical suggestion. “I personally believe that every working cop needs a checkup from the neck up every two to three years, just to get in to talk to someone about what’s going on in his or her life,” he says. He admits that the idea may not be fiscally feasible, but he believes that a program of regular mental-health assessments could end the epidemic of police suicide.

That would help more than the troubled officers themselves. A single police suicide ripples out into the family, the force and the community. More than a year after Ronald Lattimore took his life, his widow is still struggling with the effects of his suicide. “I’ll be a different person for the rest of my life,” Boges says.

Meanwhile, cops in crisis continue to find their way to the PBA and Cop2Cop, and Ussery and his colleagues are still sitting in their cubicles, picking up the phones because lives depend on it.

Leslie Garisto Pfaff is a frequent contributor on health and education.

**************************

SIDEBAR:

Where Cops Can Find Support

Since 2000, the retired law enforcement officers at New Jersey’s Cop2Cop hotline have been picking up the phones and offering confidential support and referrals to the state’s cops in crisis, who call in with issues ranging from marital and financial problems to substance abuse, post-traumatic stress, anxiety, depression and suicidal thoughts. Along with 19 helplines, Cop2Cop also offers face-to-face meetings and on-the-scene crisis intervention. They can be reached 24/7 at 866-COP2COP (866-267-2267).