The modest stub of a building on Chancellor Avenue has opened its doors to many different people over the years. First came the customers of the Rubin Brothers drugstore, a mainstay for Newark’s Jews during the mid-20th century heyday of the surrounding Weequahic neighborhood. Then, the 1967 riots and I-78 blasted through Newark, and the Jews fled Weequahic for the suburbs. The African-Americans who moved in found bargains at what had become Murry’s Meats, a discount butcher shop. Years later, a small group of faithful Christians resurrected the corner store as the New Life Missionary Baptist Church.

New Life moved out a few years ago. Since 2008, Friday afternoons have replaced Sunday mornings as the busiest time of the week at the well-worn, one-story building. That’s when Muslims stream in for jumah, the obligatory weekly congregational prayer. All that remains of the building’s past is one of the Baptist pews just inside the front door. It is used by those who need to sit to take off their shoes before they go inside to pray—for hope and peace, and on this day last June, perhaps also for assurance that they are no longer being spied on.

Early this year, the congregants learned that a special unit of the New York Police Department, on the lookout for terrorists, had been watching them where they worked, where they shopped, even where they prayed. And that gnaws at them.

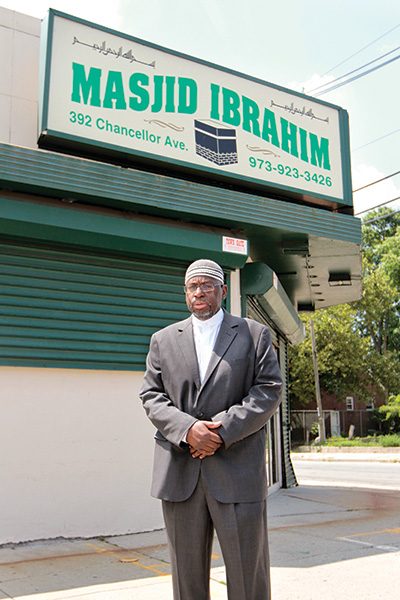

“Let not the hatred of you as Muslims cause you to swerve from justice,” Imam Mustafa El-Amin tells the 150 men huddled around him on the green-carpeted floor of what is now called Masjid (the Arabic word for mosque) Ibrahim. Women, some with young children, listen from a raised section at the end of the room where the New Life altar once stood. “Just as Jesus and the other prophets who struggled against injustice remained dignified, that’s what we need to do now,” says El-Amin.

Most of the men are African-American, like El-Amin, but in nearly all of the many rows also sit Muslims from Pakistan, Palestine, Egypt and other Islamic regions. El-Amin, who grew up nearby, delivers his khutbah, or sermon in a brown suit and open-collar dress shirt that make him look more like the 55-year-old public school teacher he is outside the mosque than the long-robed imams generally associated with Islam.

“Our religion is open to everyone,” he declares in a rich, forceful voice. Heads nod. “We have nothing to hide.”

That declaration of transparency contrasts with the message contained in the surveillance documents the Associated Press revealed in a series of stunning articles last February. Among the secret reports the AP obtained was a 60-page dossier from 2007, in which 14 Newark mosques—including Masjid Ibrahim at its original location across the street—were photographed, their congregants categorized along racial and ethnic lines. Muslim-owned businesses and their customers also were described in detail. Even Muslim schools were put under a microscope. The report used phrases like “locations of concern” and “co-conspirators” that seem intended to validate the suspicions behind the surveillance. Yet no arrests have been made.

In the nine months since the articles were published, the Muslims of Newark, along with their religious and ethnic allies throughout New Jersey, have angrily demanded to know who authorized the spying, who gave New York police permission to come to Newark, and what the police have done with all the information they secretly gathered. They have taken their demands to City Hall in Newark and to Trenton. They have met with city, state and federal officials. Some joined a lawsuit filed by a national Muslim organization.

These days, the outrage has begun to lessen, but the suspicion sown by the undercover police action lingers.

El-Amin was angry when he first heard about the spying. Then his feelings started to change. “The climate we live in is so hostile on both sides, Muslim and non-Muslim,” he says, “that to act like there is no need for intelligence is unrealistic.”

But what continues to gall him is one simple fact: Muslims have lived in Newark in significant numbers since at least the 1950s—long enough to feel part of the fabric of the city. He says Muslims hold positions of authority throughout Newark and in neighboring towns—in schools, firehouses and businesses. There have been a small number of Muslim police officers—at least since 1999, when the United States Court of Appeals upheld their right to wear beards despite department regulations requiring officers to be clean-shaven. Such progress led Newark’s Muslims to believe they had earned the trust of the greater society.

And then this.

Not only has the surveillance raised suspicions about Muslims among many Newark citizens, it has heightened some already painful tensions among the Muslims themselves. Segments of the Muslim community allow that, as their numbers grow, some of their own may need to be watched, but not in the secret way the police conducted their surveillance.

“Everything about our religion is peace and light,” the imam continues in his khutbah. “If the world is ignorant about what Islam is, we must open the doors and destroy that mountain of ignorance.”

In response to the revelations about the police surveillance, Masjid Ibrahim delivered that same message of openness in an advertisement that ran for several days in April in the Star-Ledger.

“Our doors are open,” the ad stated, as if challenging the notion that Newark’s Muslims needed to be watched—not because of what they had done (nothing in the secret reports hints at criminality), but simply because of what others think they may be capable of doing.

On several occasions—some announced in advance, others not—this reporter found that the doors of Masjid Ibrahim were indeed open. Long after the Rubins’ drugstore, Murry’s Meats and the New Life Church disappeared, the squat building—just three blocks from Weequahic High School and Philip Roth Plaza—has clearly taken on yet another life, one that in many ways reflects the unique world inhabited by Newark’s Muslims.

El-Amin, a special-education teacher in the Newark Public Schools for 30 years, believes the terror attacks of September 11, 2001, marked a significant turning point for his community’s sense of self. He remembers some of his students coming to him after watching events of that horrific day unfold on television.

“When they started showing pictures of the hijackers—I’ll never forget this—one of my students said out loud, ‘They’re not Muslims,’” El-Amin recalls. “‘Muslims look like Mr. El-Amin.’”

Indeed, during much of the last century, most Muslims in Newark did look like him. The link between African-Americans and Islam goes back to slavery, when West African captives brought Islam with them to America. That connection lasted for centuries, though it grew progressively weaker until it was revived in a new form early in the 20th century.

“Newark is a very important city for the establishment of Muslim communities in the country,” says historian Mikal Naeem Nash of Essex County Community College, who has written a book, Islam Among Urban Blacks (University Press of America) about Newark’s Muslims.

A century ago, a mysterious African-American from North Carolina named Timothy Drew showed up in Newark. He encouraged American blacks to loosely adopt some quasi-Islamic tenets, and in 1913 he founded the Canaanite Temple in Newark. He and his followers eventually spread to Chicago, where Drew, by then known as Noble Drew Ali, started the Moorish Science Temple, freely mixing a patchwork version of Islam with aggressive ideas about African-American identity.

What happened next is not entirely clear. According to some versions of the story, one of the followers of the Moorish Science Temple was a silk peddler named W. D. Fard Muhammad, who in the 1930s would play a key role in the creation of the Nation of Islam, a black nationalist group that touted separatist ideas. However, it veered from orthodox Islamic teaching in many respects, most notably in its vilification of whites and the belief that Fard was actually the personification of God.

The Nation of Islam grew strong in Newark, forming its first mosque in 1961 on South Orange Avenue in the city’s impoverished Central Ward. From it, offshoots sprouted all over the city, and large numbers of young black men and women were attracted to the sect’s alluring combination of theology and racial empowerment.

By 1975, much of the Nation of Islam, including members in Newark, having backed away from the most radical ideas of its founders, reformed the sect’s hierarchy and embraced orthodox Sunni beliefs.

El-Amin’s own journey mirrors the evolution of Islam in Newark. He was born into a devout Christian family as Robert King. He joined the Nation of Islam with his parents’ permission in 1972 at age 15, and as the organization demanded at the time, crossed out his “slave” name with an X and became Robert 105 X (the 105th Robert in the city’s Nation of Islam community). When the Nation of Islam moved toward mainstream Sunni beliefs in 1975, Robert 105 X did too, changing his name yet again, this time to Mustafa El-Amin. By 2003 he had studied the Koran sufficiently and had gathered a large enough following to establish his own mosque, a typical step for Newark’s Muslim leaders.

Many others made similar transitions, but it is impossible to say how many because there are no reliable statistics on Newark’s Muslim population. The Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) says there are 109 mosques scattered throughout New Jersey and estimates that the state’s Muslim population—a mix of African-Americans, second-generation Arabs and South Asians, and immigrants—exceeds 500,000. Some local Muslim leaders say it is far higher, with large numbers in East Orange, Paterson, Trenton, Jersey City, Teaneck and several communities in the New Brunswick area. Nationally, CAIR estimates that the largest groups of Muslims are South Asian and Arab, followed closely by African-Americans, who, CAIR says, represent 30 percent of American Muslims.

In the Newark area, African-Americans make up the overwhelming majority of Muslims, but there are increasing numbers of immigrants mainly from Southeast Asia and Africa, but also the Middle East and Europe.

“We now have a diverse ethnicity among Muslim groups who all pretty much live and worship in the same vicinity,” says W. Deen Shareef, imam of Masjid Waarith ud Deen at WARIS Cultural Center in Irvington (which was not on the NYPD surveillance list) and a senior advisor to Newark mayor Cory Booker. Until now, Shareef says, there hasn’t been a lot of direct contact between the different ethnic groups among Muslims, but, he says, “we’re trying to find ways to do more things together.”

While most of Newark’s mosques are dominated by a single ethnic or racial group, an exception is the Islamic Culture Center on Branford Place, which the NYPD did spy on. In general, while Muslims may have a mosque they consider their home place of worship, for Friday prayers they attend whichever mosque is closest. Because of its location in Newark’s business core, the Branford Place mosque attracts local professionals and businessmen as well as newly arrived immigrants. They form a racially and ethnically diverse community: the imam is from Egypt, the current prayer caller is a young man from Togo, and among the men who arrived to pray on a recent Friday were several from the African nations of Burkina Faso, Ghana, Ivory Coast, Liberia and Sierra Leone.

Saffet A. Catovic, a Bosnian-American Muslim, has attended Friday prayers and programs at the Islamic Culture Center since the early 1980s. He lived in Teaneck then, but at the time the center was one of the few mosques in Northern New Jersey. Now a real estate management consultant who lives near Princeton and works in Morris and Essex counties, he continues to attend the Branford Place mosque and is a member of the center’s board.

“We all listen to the same khutbah, but afterwards we go to different homes in different communities with different sets of problems,” Catovic relates. “That said, when something like the spying comes out, we all feel a sense of betrayal.”

Among Muslims, the reactions to the surveillance was varied. Over the years, a unique tension had built between immigrant Muslims and African-Americans, something almost no one wants to talk about publicly. “I know for a fact that many immigrant Muslims did not refer to African-Americans who belonged to the Moorish Temple Society and Nation of Islam as real Muslims,” says historian Nash. The immigrants, particularly Arabs, have deeper backgrounds in Islam. They tolerate the looser American approach, but there are limits to their acceptance. The American muslims “can explain the Koran but not translate it,” said one Egyptian man at the center, who would not give his name.

These fault lines seem to have been aggravated by the spying. African-American Muslims have a strong sense that the spying really isn’t about them, but about the immigrant Muslims. Yet despite their powers of protest—forged during the civil rights movement—the African-American Muslims complain they have been overshadowed by immigrant Muslims, especially at meetings with state and local officials. They say that is what happened in May, when Attorney General Jeffrey Chiesa briefed Muslim leaders—many of them immigrants—on the results of an investigation into the spying.

Chiesa concluded, to the dismay of nearly the entire Muslim community, that the New York City police have done nothing illegal. At first El-Amin was as outraged as everyone else in the community. But in time he agreed with Chiesa: The NYPD had done nothing wrong. But it had acted in a way that destroyed or severely damaged decades of trust.

New York City Police Commissioner Raymond Kelly has given few details about the surveillance program in Newark, but he has consistently defended it, reiterating that no laws were broken and that his officers have to do whatever is necessary to protect the city. His tough stance on terrorists has many supporters, and it isn’t difficult to see why. The New York Police Department has foiled several plots since 9/11, including the Times Square bomber.

New Jersey hasn’t been immune to the threat of homegrown terror either, although Newark Muslims have not been directly implicated in the incidents. In 2007, around the time the surveillance was getting under way, authorities broke up a ring of six radicals who planned an attack on Fort Dix. There have been other arrests, including an African-American Muslim named Sharif Mobley from South Jersey whose detention in March 2010 set off alarms when it was learned that he had made contact with the leader of a terrorist group in Yemen after working at PSE&G’s nuclear complex in Salem County.

Still, it’s hard to see what the surveillance in Newark accomplished. At a meeting with several imams after the spying was made public, El-Amin was told by Chiesa that the authorities were following specific leads at each of the 14 mosques. Finding that hard to believe, El-Amin asked for details but has gotten none.

It appears just as likely to some Newark Muslim leaders that the targets were selected simply because they were Muslim. It is an approach that many find detestable. “Here we are, worshiping with the intentions of hearing the word of God, and at the same time there’s a conspiracy taking place against us—that sends a chill,” says Akbar Salaam, a member of Masjid Ibrahim and owner for more than 40 years of the Unity Brand Halal Products in Newark. Like Masjid Ibrahim, Unity was on the list of Muslim locations the police tracked.

Salaam says the spying was a waste of money. If he could speak with Commissioner Kelly, he says he would tell him point blank: “You have no reason to fear from us.”

What’s more, as an exercise in data collection, the surveillance got many things plain wrong. “The information they spent taxpayer money getting, I could have given them for free in an hour,” says Amin Nathari, an author and prominent speaker in Newark’s Muslim community. He says the police report erroneously lists the ethnic composition of the Islamic Cultural Center as African-American, when it is an obvious ethnic mix. And the Masjid Imam Ali K. Muslim, a mosque on South Orange Avenue, is characterized as belonging to the Nation of Islam, even though it broke away, like many other Newark mosques, in the 1970s.

For many of Newark’s African-American Muslims, the news they were being spied on came as no surprise. “As soon as we became Muslim, we knew we’d be watched,” says Kauthar Ali, a member of Masjid Ibrahim who joined the Nation of Islam 45 years ago. She now wears a hijab and follows orthodox Sunni ways. For her, the spying is “disconcerting, but nothing new.” Like other Muslims, she believes members of the community were being watched by the FBI and local authorities as early as the 1960s. Although El-Amin also says he has been spied on before, he says he has come to understand Commissioner Kelly’s need for information. The problem, he insists, is the manner in which the watching was, or is, being done.

“I’ve got all kinds of people coming in here, so I welcome the surveillance,” he says, “just not secret surveillance. They could have spoken to us.” He says that if the police had approached, he would have cooperated, just as the Muslim community has helped in Newark’s fight against gangs and drugs. And he says the police would have found out that his masjid does not tolerate violence.

“A guy came here maybe a year or so ago,” El-Amin says, recalling the time when a man at Friday prayers started putting a positive spin on the Muslim Army major who shot and killed 13 soldiers at Fort Hood, Texas, in 2009. “I told him, ‘You might need to watch what you’re talking about and don’t be bringing that stuff up in here.’ Then I let some other fellows know, ‘You keep your eyes and ears open.’”

That man stopped coming to Friday prayers.

It seems to El-Amin that New York police may have outdated notions about black Muslims going back more than 40 years, to the outspoken days of Malcolm X and the Nation of Islam. After all this time, he says, the law-enforcement community should know better.

“They’ve been watching us for a long time and they should have come to the conclusion that, ‘We don’t need to watch Mustafa’s mosque. They’re all right.’ That would have been our point. If you watched us long enough, you know us, you know darn well we’ve evolved.”

The imam also has trouble fully accepting the public statements by Governor Chris Christie, Mayor Cory Booker and Samuel DeMaio, Newark’s police director, that they were unaware of the spying before the story broke.

Something else bothers him, and other Muslim leaders. Beyond the documents that have become public, they do not know the extent of the information the police have collected. El-Amin worries that his wife and family might have been watched and that his phone may have been tapped. Although the NYPD will not comment on the investigation, in early September, El-Amin attended a meeting at the office of the New Jersey attorney general in which Edward Dickson, director of the New Jersey Department of Homeland Security and Preparedness, said the NYPD Demographics Unit was no longer working in New Jersey.

“At least that’s some progress,” El-Amin says. “Six months ago they couldn’t assure us that the surveillance had stopped.”

The questions that El-Amin has been asking are the same as those posed by 65 Muslim leaders at the Siegler Hall Auditorium at Essex County Community College the first Friday of June. It was a special meeting called by the Muslim Community Leadership Coalition, a group formed in response to the surveillance controversy. Many imams are involved, but Mustafa El-Amin is not one of them. He says he prefers to go his own way. Others call him a maverick.

Those at Siegler Hall that night worried about the long-term impact the surveillance would have on Muslims in Newark, and on Newark itself. Muslim shop owners have reported declines in business that they can only hope are temporary. Attendance at mosques has reportedly dipped, and people are afraid that the secret presence of the New York police has sent a message that Newark needs to be watched.

It is a perception that concerns non-Muslims too. “From the community perspective, this practice is disdainful because it portrays the city in another violent light,” says Right Reverend Mark Beckwith, bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Newark and a member of the Newark Interfaith Coalition for Hope and Peace—along with Shareef, imam of Masjid Waarith Ud Deen in Irvington, and Rabbi Matthew D. Gewirtz of Temple B’Nai Jeshurun in Short Hills. “What it says is that if something bad is happening, it must be happening in Newark. And that’s not so.”

Most of the people at the meeting were still smarting from the attorney general’s announcement that the police surveillance did not violate New Jersey laws.

“What we want to know is, are we as citizens entitled to equal protection of the law?” asked Kenneth Dawud Hall, a lawyer who briefed the group on the attorney general’s decision. “If we are protected by the laws of New Jersey the way others are protected, then where’s the 60-page report on Catholics? On Jews? On Buddhists? What they did is akin to racial profiling, which is illegal in the state of New Jersey.”

The Muslim Community Leadership Council has asked for help from Muslim Advocates, a national organization based in California. Glenn Katon, the group’s legal director, told the group at Siegler Hall that he believes the constitutionally guaranteed civil rights of Muslims in New Jersey have been violated.

As expected, less than a week after the meeting, Muslim Advocates filed a lawsuit in federal district court in Newark against the NYPD. “By targeting Muslim organizations and individuals in New Jersey for investigation solely because they are Muslims, or believed to be Muslims,” the suit charges, “the program casts an unwarranted shadow of suspicion and stigma on plaintiffs and, indeed, all New Jersey Muslims.”

Among the plaintiffs is Akbar Salaam and his Unity meat market. El-Amin has declined to join the suit, preferring to focus on reconciliation. He knows that others in the Muslim community criticize the stand he’s taken, but he says he doesn’t care.

“I’m not going to flip around and file a lawsuit after inviting them here to see what we’re doing,” he says. He supports the right of others to go to court, but he says he will continue to focus on “educating people about our religion and what we are about.”

The lawsuit asks the district court to stop the surveillance, which it contends is continuing. It also demands the destruction of all information that has been collected illegally and a declaratory judgment that the surveillance was unconstitutional.

On the first Friday after the lawsuit was filed, a stocky man in a knitted skullcap holds his hands to his ears and begins the call to prayer inside the carpeted main room of Masjid Ibrahim. The masjid does not follow the custom of making the call outside with loudspeakers out of respect for the surrounding neighborhood, which is overwhelmingly Christian. El-Amin’s own mother, Annie King, still lives nearby and remains a devout Christian.

But signs of change are everywhere along this section of Chancellor Avenue. The hot dog vendor a block away from the masjid sells only halal beef hot dogs. The Chinese restaurant two blocks away also is halal.

As the neighborhood changes, so does Masjid Ibrahim. A Palestinian car dealer with a lot on Chancellor attends Friday prayers, as does a limo driver from Pakistan. Mohammad Masalam, also from Pakistan, is a Postal Service letter carrier who lives in Woodbridge but whose delivery route now covers Chancellor Avenue.

Masalam says he started coming to Masjid Ibrahim just before the surveillance program was revealed. He says he was surprised to learn that the police were monitoring the mosque.

“I don’t know why they did this to us,” he says, more perplexed than angry. He hopes the spying has stopped but is not convinced.

Near the end of his khutbah, this Friday, El-Amin allows a hint of old-time Baptist revival to slip into his delivery, a trait he inherited from his grandfather, a Georgia Baptist preacher. “All praise be to Allah,” he exults. “When a force that is bigger than us comes upon us, what do we do?” He raises his arms as high as his voice.

“Do we blow ourselves up? No.” Voices from the floor murmur in response.

“Do we terrorize people? No.

“We beat it back with our intelligence,” El-Amin roars. “And with our faith.”

The khutbah ends at two minutes past two, and every man in the masjid—no matter where he comes from or what he is wearing, regardless of what language he speaks at home or what kind of food he sets on his table—each one bows low and recites prayers in Arabic, the same prayers said for centuries in every mosque around the world.

After they finish, some sit on the old pew from the Baptist church to lace up their sneakers or shoes. Then they venture into the glare of a June afternoon in Newark, heading in every direction.

And the old building on Chancellor Avenue, reincarnated so many times for so many people, place of such hope and such suspicion, is quiet once again.

Anthony DePalma is the writer in residence at Seton Hall University and author of City of Dust: Illness, Arrogance and 9/11 (FT Press, 2010).

If you’re not doing anything suspicious, then you have no worries. Shut up and suck it up. No Syrian refugees! TRUMP 2016

Keep up the good work; we need protection. It can’t all be about their ‘feelings’ when Islamic terrorism is a clear and present danger in America. Get Real.