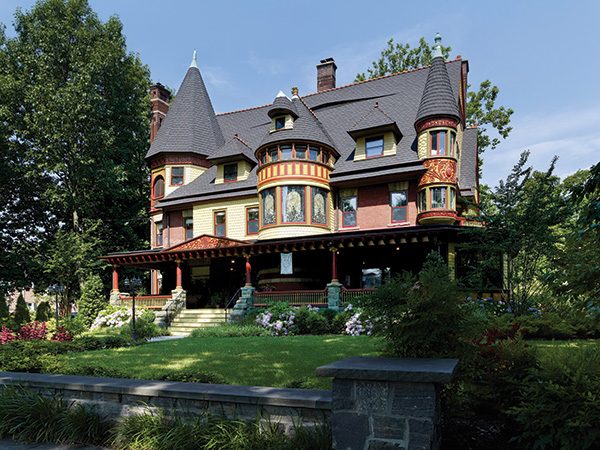

When John Stewart and his partner, Craig Bowman, happened upon this house in Plainfield seven years ago, kismet ensued. “We had an aha moment,” Stewart explains. “I’d always been drawn to contemporary architecture, but when we first looked at this house, we were like, ‘Wow!’” A splendid Queen Anne Victorian, the house was built on West Eighth Street in 1893, during an influx of Wall Street wealth to Plainfield following the completion of the railroad line connecting it to New York City.

In fact, West Eighth Street at the time was known as Millionaire’s Row. By the time Stewart and Bowman came across it, the 7,500-square-foot mansion, designed by architect Charles H. Smith for attorney Craig A. Marsh, had changed hands many times, fallen into disrepair and been divided into four separate apartments. (In one of those apartments, Stewart says, a tenant had lived with 12 cats.) Still, the men saw something noble, not just in its bones, but in its possibilities. “This type of history should be preserved and shared,” Stewart says.

“These are stately homes with amazing stories.” Setting to work, the couple—Stewart, who works in corporate communications, and Bowman, a lawyer,—would create an amazing story of their own.

There was no question the house was worth preserving. Its assets include a grand wraparound porch, turrets, intricate stained-glass windows, an elaborate staircase and exquisite interior woodwork. The pair embarked on an end-to-end renovation that consumed more than five years at a cost that ultimately exceeded the purchase price of the house itself. The first step was to convert it back to a single-family residence. Stewart found the original floor plans and hired an architect to figure out what went where. Down came several walls, along with two second-floor kitchens.

Next they brought in a general contractor to assess the project and map out the order in which the work would be done. With much of the wood rotting and the slate roof leaking and sagging, structural repairs came first. The pitch of the roof is so steep and the slate so heavy that, once water gets in, it causes a ripple effect, rotting everything in its path. The roof was replaced with a slate-like synthetic that is lighter and requires much less maintenance. The enclosed porch was entirely redone, and the entire exterior received a face-lift. But only a face-lift. Maintaining the original front—a mix of Philadelphia green stone, pressed brick, terra cotta and stained cedar shingles—was essential if the job was to earn historic preservation designation.

Fortunately, the woodwork was in pretty good condition, but much of it had been painted over. Stripping it became a major task. “There were four layers of paint in the dining room, with this beautiful wood underneath,” Stewart says. Crown molding was replicated or restored in many of the rooms. Another major challenge was repairing the stained-glass windows. The pair did their research and found a local expert.

Throughout the house they added new systems, including electricity, plumbing and central air conditioning. Each of the 3½ baths were restored to resemble the originals. The four fireplaces—magnificent marble and mosaic structures—were refurbished, as were the parquet floors, which have a slightly different pattern in each room. Stewart and Bowman used a 1983 New York Times article about the house to research its original paint colors and matched them as closely as possible.

During every phase of the project, Stewart and Bowman were thrilled with the neighborhood’s support, from helpful advice to frequent social gatherings. “This community opened its arms,” Stewart says. “We bought a great home, and a great community came with it.” Their house is one of 152 within the Van Wyck Brooks historic district, the largest and most active of Plainfield’s 10 historic districts.

Now, not surprisingly, Stewart is president of the Van Wyck Brooks Historic District, helping to research its legacy and consulting with homeowners tackling their own preservation projects. “New Jersey has such a significant architectural heritage,” he says. “I feel very fortunate to live in a place that has history.”

**********************

Why is Historic Preservation Important?

“Once a house is knocked down, it’s gone,” says owner John Stewart. “There are pockets of New Jersey that need to be preserved; their stories should be shared.”

Michael Calafati, AIA, an architect in Cape May and chairman of the AIA-NJ Historic Resources Committee, explains that preservation is a very big component of architecture. “A great deal of an architect’s work is working with existing buildings,” he says. Why not just knock that existing building down and start from scratch? First of all, historic preservation is environmentally friendly, Calafati says. “Retaining older building stock, making it viable again, is extraordinarily green friendly,” he points out. In addition, historic preservation highlights the aesthetics of past eras. “The best examples of domestic architecture in the entire world are American homes,” Calafati asserts. “These buildings are an expression of the United States, be it a Frank Lloyd Wright or a Queen Anne Victorian.”

Where should the would-be preservationist begin? With extensive research. “It’s important to know and understand the history of your home prior to starting a restoration,” says Stewart. Check the local library, town hall or historic district for blueprints, old postcards, tax and sales records, even previous renovations. Then, rely on trusted experts. There are well-qualified architects and contractors who deal with preservation all the time, says Calafati. “What the homeowner can do is invest a little more time and effort in interviewing their architect and their contractor,” he suggests. It’s worth the extra effort. “Architecture is the most public of all art,” Calafati concludes. “Our history is the buildings we leave behind. When we knock down that building, we’re erasing our history.”

For further information on historic preservation, contact Michael Calafati, AIA, Cape May, 609-884-4922.

My deepest thanks to whomever comes into Plainfield to restore all its grandeur. My family was born and raised there. There are many lovely homes that could be restored. It breaks my heart to see it in disrepair. Thanks..so much!