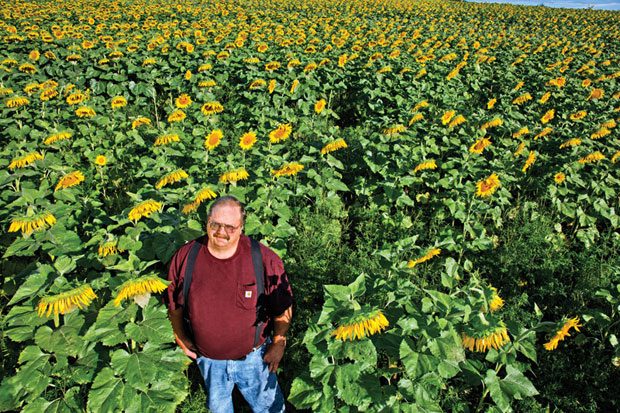

Mark Kirby sometimes has to stop and marvel at the acres of dew-laden sunflowers undulating across his Hillsborough farm, their golden heads lifted to the sun. “As farmers, we like to play in the dirt and watch things grow,” he says. “But looking at a whole field of bright yellow sunflowers, it’s an incredible sight, even for us.”

Sixty miles north, in the Sussex County town of Augusta, farmer Raj Sinha admires his 70 acres of sun-kissed stalks. “I walk the field and am always taking pictures,” he admits.

Sown in the spring, sunflowers grow by early fall into mature plants up to 7 feet tall. Their heads, wide as sombreros, become weighty with seeds and turn downward like penitents. That doesn’t stop birds from latching on with their claws and hanging upside down, feasting on the nutritious seeds. Bees, bats, moths and other insects also feast on the plants and beneficially spread their pollen.

For New Jersey farmers, sunflowers have presented a new opportunity to diversify their crops. And thanks to farmers like Kirby and Sinha, who open their fields to visitors on specific dates, the crop contributes to Jersey agritourism.

New Jersey’s sunflower farms account for just 1 percent of America’s $700 million sunflower industry. North and South Dakota are the heartland for U.S. sunflower cultivation, representing about 75 percent of the crop. Globally, Russia and Eastern Europe are big producers.

That’s a concern for environmentalists, who would prefer a source for the seeds closer to the populous East Coast. “There’s a high carbon footprint involved in transporting the seeds for sale here,” says John Cecil, vice president for stewardship at New Jersey Audubon’s Wattles Stewardship Center in Port Murray.

To reduce our dependence on distant farms, New Jersey Audubon, with support from the state Department of Agriculture, created a program called SAVE (Support Agricultural Viability and the Environment). Launched in 2008, SAVE has so far recruited 14 New Jersey farmers to grow sunflowers and harvest the seeds. The program buys the crop from the farmers and sells it as birdseed statewide. SAVE also supports the environment by establishing 1 acre of grassland habitat for wild nesting birds for every 5 acres planted in sunflowers.

In a state with 735,000 acres of farmland, the 200-plus New Jersey acres currently devoted to sunflower production seem like a tiny contribution—as small as a sunflower seed, you might say. But modest beginnings can lead to major effects.

Kirby has grown 14 to 28 acres of sunflowers for each of the last five years on Derwood Farms, his 400-acre spread in Somerset County. Though he still raises corn, soybeans, wheat, oats, hay and beef cattle, “we felt sunflowers had a lot of potential,” he says. “They work into a nice rotation with our grain crops, enable us to sell seeds to New Jersey Audubon and other outlets, and open the possibility of selling sunflower oil too.”

Kirby, the 58-year-old chairman of Somerset County’s Agriculture Development Board, leaped at the chance to diversify. “It gives me another avenue to make money if something else fails, and provides us more lobbying power on other agricultural issues in Trenton,” he says. Once a year, he opens his farm for a tour led by New Jersey Audubon.

Sinha, 41, saw additional possibilities for the flaxen flower. “Five years ago, we were approached about being a northern grower in the SAVE program, and we said, ‘Let’s give it a shot,’” he says. Sinha and his wife, Jolene, initially devoted 10 acres of their fruit and vegetable farm to sunflowers. “When we planted the first field, the sunflower views were just breathtaking, and people were always taking pictures of it from the edge of our field,” he says. “We wanted to do something to share it.”

The following year, Sinha planted 30 more acres of sunflowers and cut a maze for visitors to “interact with the sunflowers.”

The 3-mile-long maze has become a popular attraction, running for roughly six weeks each year starting sometime in August. Sinha cuts a 5-foot swath through his field, spelling out a message, such as “We Are Jersey Grown” or “Jersey Devil Salsa”—a reference to one of the farm’s signature products. [Click here to see all there is to do at Sinha’s farm.]

“It’s the largest sunflower maze on the East Coast,” Sinha claims. “People come from all over to see it.” The Summit native attended veterinary school and operated other businesses before deciding about nine years ago to pursue his passion for sustainable farming. “People can see the whole 70 acres, as well as all of the birds, butterflies and native pollinators from a hill overlooking the farm,” he says. “It’s an incredible way to enjoy nature.”

“The sunflower maze is so gorgeous and photogenic,” says Rosalynn McEvilly, 33, a resident of nearby Hampton Township. She visits the maze each year with her young daughter to walk among the sunflowers and take part in maze activities such as the insect treasure hunt. “It’s a great family outing that helps teach kids the importance of the circle of life,” McEvilly says.

Across the road, Roseline’s Farm and Bakery serves farm-fresh breakfast and lunch to the maze-goers. Roseline and Tico Lin also sell sunflower bouquets, and Roseline sometimes includes the edible, yellow sunflower petals in her signature salads. The Lins, who have owned their 186-acre farm since 1988, lease 40 acres to Sinha for sunflower cultivation.

Commercial black oil sunflowers—named for the black hulls of their seeds—are ready for harvest in the fall when their 12- to 18-inch wide heads—or rosettes—droop downward from the weight of their seeds. First they have to survive a number of challenges. “Bears and deer, which seek the highest calorie diet they can get, are a threat to sunflowers, and most fences don’t protect against them,” says Sinha. One year, he lost 10 acres to deer damage. Sunflowers also fall prey to viral infection (rotating crops annually can prevent this) and can be damaged by adverse weather.

It takes about 350 flower heads to fill a 25-pound bag of seed. “We currently average about 900 to 1,200 pounds of seed per acre and are working with fellow farmers to share best practices so that we can increase our yield,” Kirby says.

“A decade ago, sunflower production in New Jersey was virtually nonexistent,” says Doug Fisher, New Jersey’s Secretary of Agriculture. “Now it’s a multifaceted niche business that helps strengthen and diversify our farms.”

Some of the positive effects can’t be quantified. “Sunflowers bring a lot of joy to people,” says Sinha. “I can’t tell you how many visitors thank us for all the work we put into the maze and for sharing such a beautiful experience with them.”

Susan Bloom is a Chester-based freelance reporter.