Until Dec. 11, 2007, Sandi Roberts knew little more about the legal system than what she saw on Law & Order. But on that cold, clear morning, the retired physical therapist was horrified to find a scene at her parents’ Cherry Hill condo straight out of a TV drama.

Opening the door to the apartment, Roberts discovered her 82-year-old father, Sidney Wenof, lying on the living room floor, blood pouring from his bludgeoned head onto the cream carpeting. The family caretaker, Yalanda Steele, was standing over him as Roberts’s mother, Theora Wenof, 83, sat stunned and motionless on a chair.

Steele, a 32-year-old Camden woman, told Roberts that her father had fallen and hit his head on a glass coffee table. The truth, it would later be determined, was Steele took an aluminum cane and savagely beat Sidney Wenof over the head with it, breaking his skull and leaving his face a bloody pulp. The elderly man had discovered that Steele had been stealing from his checking account for months and running up bills on his credit card.

When medics arrived, Wenof, in faltering voice, managed to tell them what had happened, and they called police. Steele was arrested. Wenof, a six-foot-tall World War II veteran and retired Camden butcher shop owner, died eight days later at Cooper University Hospital in Camden.

In news accounts, considerable attention is paid to the treatment of persons accused of violent crime. Often overlooked, however, is the plight of the victims of violent crime and their families. Yet there are, in New Jersey and nationally, people whose job it is to look after the welfare of victims, to lead them by the hand through the thickets of the legal system, and deal with their emotional distress, often long after perpetrators have been caught and convicted. In New Jersey, they work for little-known, sparsely staffed, and probably under-appreciated units, the county offices of Victim-Witness Advocacy.

The day after her father’s death, Sandi Roberts received a phone call from Linda Burkett, coordinator of the Camden County Office of Victim-Witness Advocacy. In her 24 years as coordinator, Burkett has made countless such initial phone calls.

“When we are speaking with someone in that situation, they need a lot of things,” Burkett says. Sympathy and condolences come first. “During that first phone call, some people are emotional, some can’t even come to the phone, some are calm,” she says. “We can’t assume everyone is going to react in a certain way. So we try to basically prepare the family for what they’re going to encounter with the legal system.”

Usually the answers bear repeating. “It’s often very difficult for survivors to process everything we’re saying,” Burkett explains. “They may hear every third word, because their minds may be racing far in advance.” The phone calls always end the same way. “I tell them I am here to help them through the criminal justice system and with any problems they have,” Burkett says. “I tell them they can call us at any time, and I promise a person will get back to them, because it’s frustrating when a machine picks up.”

Roberts, 58, the second of three sisters in a close-knit family, bonded with Burkett immediately. “She was very comforting from the beginning,” she says. “Linda never, ever left us.”

The advocacy office is tucked away in the Camden County prosecutor’s building, a grayish, concrete fortress located between a gated parking lot and a methadone clinic and across the street from a boarded-up office building. Inside, receptionists stationed behind tempered glass assess the walk-ins, including a man who recently insisted that aliens were communicating through the fillings in his teeth.

A plain door leads to the advocates’ suite. It is a relatively cheerful domain. Sliced watermelon and soft pretzels sit on a table in the entryway for clients and workers. The white walls are freshly painted, and light spills into a central area where assistants answer calls and shuttle messages to the advocates stationed in plain, shared offices.

Each of New Jersey’s 21 counties has an office of victim-witness advocacy. In 2009, the Camden unit assisted 6,375 individuals with new incidents, making Camden County the third busiest office after Essex and Hudson counties. In terms of total number of services provided, Camden ranked second after Essex. Camden County’s clients included the parents of a high school student randomly shot to death outside a Camden fried chicken joint; a middle-aged woman whose ex-husband slashed her tires and poured sugar in her gas tank; and a 5-year-old girl whose step-brothers raped her with the encouragement of their foster parents.

The six advocates, all women, are assigned to individual investigative units of the prosecutor’s office—one each for homicides, major crimes, domestic violence, juvenile offenses, and child abuse, and one “trial team” advocate, who can handle any of those, plus crimes in other categories. “There’s never any lack of business,” says Mary Kay Baker, who advocates for domestic violence victims.

In New Jersey, assistance for crime victims dates to the Criminal Injury Compensation Act of 1971. Nationally, victim assistance stems from a 1982 Task Force on Victims of Crime commissioned by President Ronald Reagan. The panel took testimony from 187 witnesses in six cities. The statements left task-force members appalled: defense lawyers routinely booted victims out of trials, families had to rely on news media to follow their cases, and court officers would unwittingly instruct rape survivors to sit next to their accused attackers in hearings.

“I will never forget being raped, kidnapped, and robbed at gunpoint,” a victim told the panel. “However, my sense of disillusionment [with] the judicial system is many times more painful.” Task force member Kenneth Eikenberry, then attorney general of the state of Washington, admitted that “after working with all of these victims, I really had not comprehended what happens to them, what they go through, and how their lives change forever in so many instances.”

The 144-page report made waves. The federal Victims of Crime Act, passed in 1984, established a Crime Victims Fund to support a spectrum of programs helping survivors and their families.

A week after her father’s death, Sandi Roberts and her two sisters had their first meeting, called a “sitdown,” with Burkett and the assistant prosecutor for their case. They briefed the grieving women on the status of the case and the exasperatingly slow court proceedings that were likely to ensue.

“We don’t make any promises,” Burkett says. “We’re really honest with people. We have no control over a case. As long as [the family] is kept in the loop, at least they’ve been treated with respect. Sometimes that’s all you can do.”

What most victims want to know, Burkett says, is why they were victimized. “Why them? And what kind of person could do that to them? We hear this most times at sentencings. Some of it I can answer and some of it I cannot. Being able to live with those questions is something that, at least, you can kind of help people with.”

Burkett had been a special ed and elementary school teacher before she became a victims’ advocate in 1987, when the office was new. “It was on-the-job training,” she says. Deciphering legalese, she says, “was like learning a foreign language. What surprised me is that there was resistance at first to victims’ services, from courts, from some prosecutors.” But the advocates were able to change minds because their mission, in Burkett’s words, is “taking on jobs other people don’t like to do, like talking to people who are emotional and upset.”

“Their hands-on approach is very important,” says Timothy Chatten, deputy chief of the Camden prosecutor’s office that handles juvenile cases. Chatten meets with his advocate liaison frequently across stacks of case files to discuss the well-being of victims. “With my case load, I can’t be in touch, face-to-face or even by phone, with every victim,” Chatten says.

There is no single career path to becoming a victim-witness advocate. Burkett hires workers based on their listening skills, street sense, and ability to think on their feet. Nearly all the legal expertise is acquired on the job. Some advocates say they need more mental health training to deal with troubled clients and to prevent their own burnout. “You have to be solid enough that you’re not bleeding all over the people you’re trying to help,” says Burkett, who is 61 and divorced. “I have good people in my life, and that’s really important.”

Burkett’s office lost one advocate to budget cuts in 2008; today their workload is staggering. Faxes detailing fresh crimes spill into the Camden office as many as 25 times a day, triggering a phone call from an advocate to the victim or the victim’s family. The office is also notified when offenders are paroled, let out on bail, or are eligible for release from custody. Advocates attend restraining-order hearings, offering help to domestic violence victims.

Advocates say each situation is unique, as are their responses—whether making sure a victim has eaten that day, combing thrift stores to find clothes for court appearances by witnesses who lack suitable attire, or finding a safe refuge for a battered woman. Another of the office’s responsibilities is dealing with witnesses who are not victims, some of whom may need relocation for their own safety.

“So much of what we do is triage,” Baker says. “I’ve bought people breakfast, I’ve held people’s hands when they throw up. I’m a grief counselor. You name it.”

Not all victims or witnesses are willing to accept help. Some fear the prosecutor’s office. Some view the advocates as nosy social workers. Others just want to crawl under a rock. Some victims of domestic violence return to their partner, and the abusive cycle often begins anew.

Roberts had no such qualms. “There is a lot to know about, and my family knew nothing,” she says. “Linda explained what would be next, and what would be next after that. She was wonderful. I honestly don’t know what I would have done without her.”

Burkett helped process the compensation forms for the family, who used $5,000 from a compensation fund for Wenof’s funeral. The fund comes not from taxpayers but from fines levied against criminal defendants when convicted in municipal, state, and federal courts.

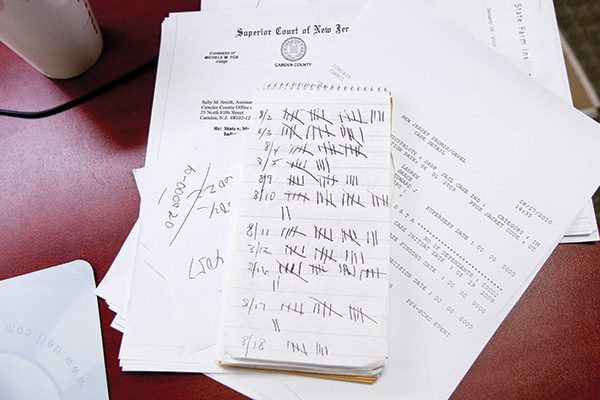

The Wenof case went through twenty court proceedings, with Roberts and Burkett speaking frequently throughout two excruciating years. Court days took on a rhythm: Burkett opened the office’s gated parking lot for the family (“She would give everybody a big hug,” Roberts says), walked them to court, sat with them during hearings to offer sympathy and legal explanations, and comforted Roberts and her sisters afterward in a brightly painted sitting room in her office. She always had tissues stuffed in her pockets for them.

“It’s overwhelming enough to deal with your family member being murdered,” says Mary Alison Albright, an assistant prosecutor for homicides in Camden County, “but then there’s all the miserable bureaucratic crap that goes along with that.” The advocates, she says, “shoulder a lot of the emotional burden with the families, which helps us to maintain our objectivity. I couldn’t do my job without them.”

In 2003, Roberts’s mother was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and given a year to live. Roberts devoted herself to her mother’s care. By early 2008, Theora’s cancer, which had been in remission, was rapidly advancing. In April, given the likelihood that she might not survive long enough to testify at a trial, the judge allowed her testimony to be videotaped in court at a pre-trial conference. She was on the stand for two hours. Yalanda Steele was present, and must have been shaken by her former employer’s forceful words.

“She got off the stand, came back to me, and said in a whisper, ‘Did I do all right?’” says Burkett. “I said, ‘Yeah, you did good.’ She was so sweet.” Theora died at age 83 in May 2008. She and her husband had been married 62 years.

The case never went to trial. On July 2, 2009, Steele pleaded guilty to aggravated manslaughter. At that pleading, the judge asked Steele for an account of the events of December 11, 2007. The three sisters leaned forward anxiously.

Standing in a red prison jumpsuit, her arms in shackles, Steele whispered, “I came and hit his cane on his head. He fell in the living room.” The sisters collapsed in tears in each other’s arms.

Burkett had helped Roberts and her sisters prepare victim impact statements, which they delivered in Steele’s presence at her sentencing that August. Roberts’s husband, Mark Roberts, read the statement that Theora Wenof had written. Addressing Steele, Roberts said, “My father was so kind to you. He did not deserve to die this way. I will never be satisfied that justice is really served here. No amount of years served can bring my father back.”

Steele was sentenced to 25 years in prison. She was ordered to pay $5,000 to the state in restitution for the funeral costs and $10,184 to the Wenof family, the amount she stole from them. The money will be deducted from whatever Steele earns working in prison. After the sentencing, Burkett gave Roberts a long hug.

All along, Burkett had been urging Roberts and her sisters to avail themselves of psychological counseling, which would be paid for from the compensation fund.

“I kept saying, ‘No, no, no,’ because I was just so focused on my mother,” Roberts says. “My mother needed assistance because of the cancer. I just needed to be there for whatever she wanted.”

But after her mother died, Roberts relented and began weekly sessions at the nonprofit Counseling Center for Trauma and Grief clinic in Moorestown. She continued going weekly until August of this year, and now goes every other week. Roberts found the sessions so helpful that the family decided to donate all the restitution money from Steele to the counseling center. “They really need the funding,” she says.

So do the victim-witness units. “In this state,” says Burkett, “we’ve come a very long way in terms of victims’ rights. But funds are drying up. I don’t know what’s going to happen. I don’t think it looks really good.” She adds, “I’d love to be wrong.” The current annual budget (through May 2011) is $485,456. Of that, $300,031 comes from federal Victims of Crime Act funds. The rest is picked up by the Camden County prosecutor’s office. By contrast, the 2005-2006 budget was $717,780, of which $574,224 came from VOCA.

“I had a $10,000 emergency fund for victims’ aid, which helped with emergency relocations, like for domestic violence victims,” Burkett says. “I used to have a Home Depot account for repairing kicked-in locks and other damage. We used to send advocates out of state for training. We don’t do that anymore.”

Cases like Wenof’s may reach legal resolution, but emotional resolution is something else. “Many victims expect that once there is a sentence it’s all over, but it’s not,” Burkett says. “They may be preoccupied with the aftermath, whether it’s medical bills, damage to their homes, or damage to relationships that will never be the same.”

And those are just the ones who see justice done. When the accused are acquitted or—in about 5 to 10 percent of cases—when no arrest is ever made, “it is very difficult to live with,” Burkett says. “Because then they never know. Is the perpetrator living across the street? Is it somebody who’s watching them? Am I going to be targeted again? For some people who have lost a loved one and there has been no arrest, it’s devastating. It’ll kill you. It’ll absolutely kill you.”

Roberts still checks in with Burkett every once in a while just to see how she is doing. Someday there may be a legal reason. “One of our assistant prosecutors was talking to me about a computer system we use to track cases, and he said to me, ‘So how many of these cases are closed?’ I said, ‘None of them, unless the victim or the victim’s survivors are deceased.’ We deal every single day with cases that have already been sentenced, but have come back on post-conviction release motions or some sort of appeal. These cases come back. I don’t close out anything.”

Heather Haddon, a Morris County native, is a reporter for the New York Post.