Mixed-media artist Wayne Brezinka, 53, is a Minnesota native who moved to Nashville in the ’90s with the hopes of working in the music industry. He’s since designed album covers and tour posters for such artists as Willie Nelson, Robert Plant and Alison Krauss. These days, he fashions 3-D paintings-slash-sculptures from an eclectic assortment of found objects.

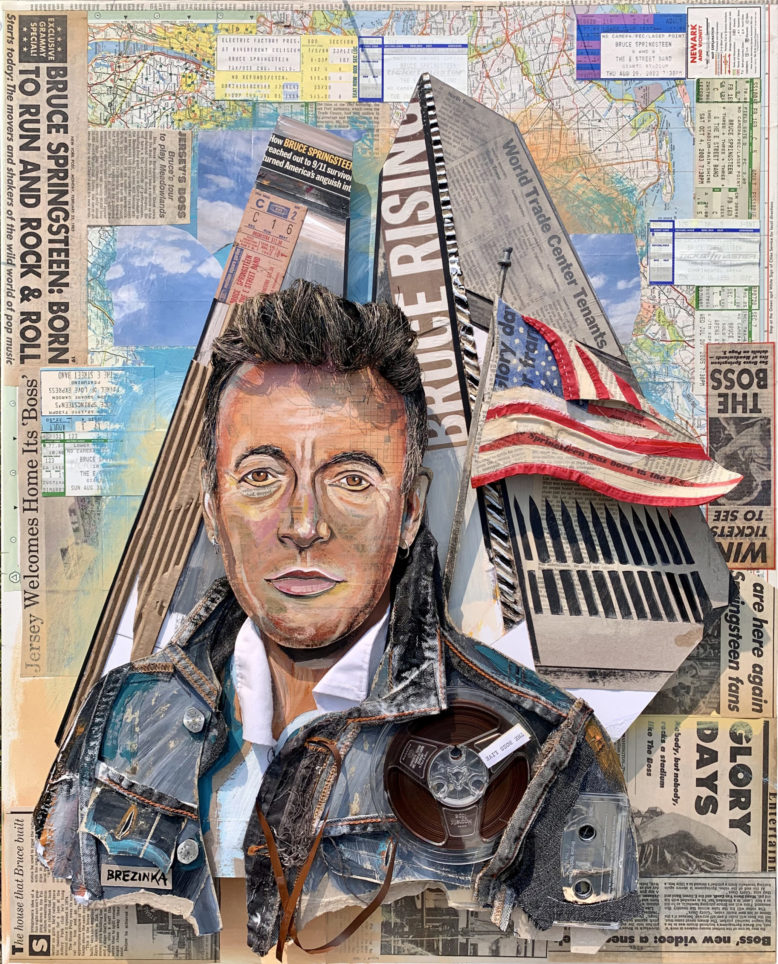

For the September issue of New Jersey Monthly, our associate art director, Andrew Ogilvie, commissioned Brezinka to create a portrait of Bruce Springsteen to accompany associate editor Gary Phillips’s essay on the 20th anniversary of The Rising album.

We recently spoke with Brezinka—an avid Springsteen fan himself—about the assignment.

When you took on this commission, where and how did you begin?

My work is both part painting and part sculptural, so it’s very 3-D and dimensional. In that process, years ago, I started to pull and find objects and images and different ephemera—pieces of paper that relate to the subject that I’m bringing to life.

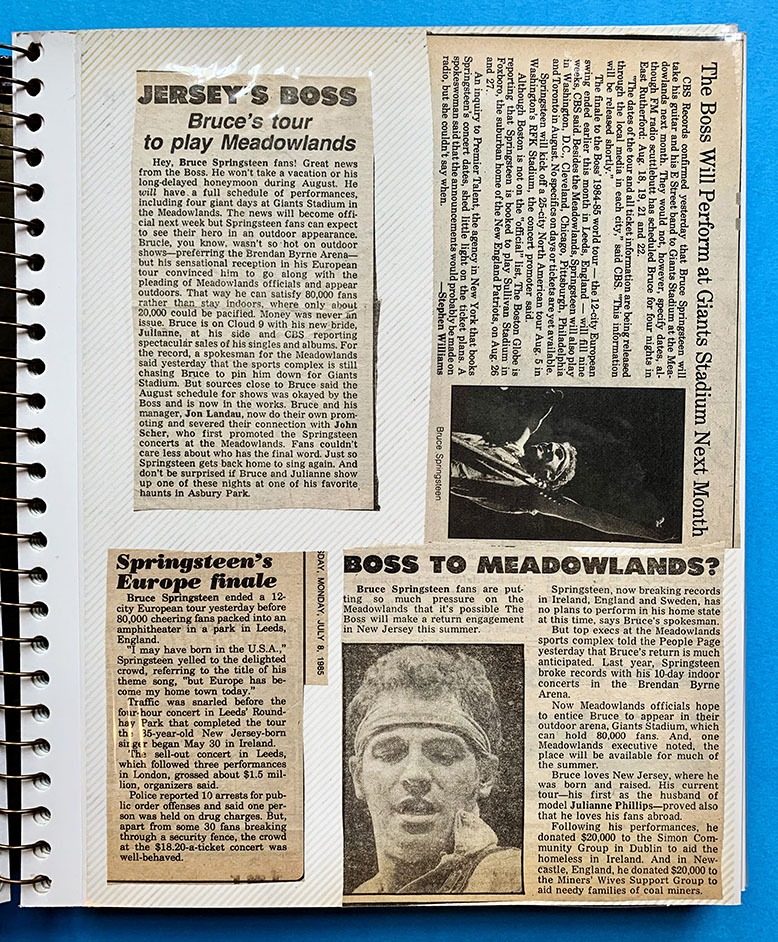

In this case, for Bruce, I was like, Okay, I need to go to eBay. What cool things related to Bruce can I find? And I found newspaper clippings from two photo albums that some person in New Jersey kept. They’re dated 1985. It was a gold mine—only, like, 10 bucks for both of them. I was immediately like, Oh, my God. I freaked out; I bought ’em right away. That’s a gold mine—to be able to pull all of those headlines that pertain to Bruce and work those in. And then I found a cover story from the Wall Street Journal, I think. There’s some text in the piece—very minimal, because I didn’t want to use too much. On one tower, you can see a headline: “World Trade Center Tenants.” There are also maps of New York and New Jersey.

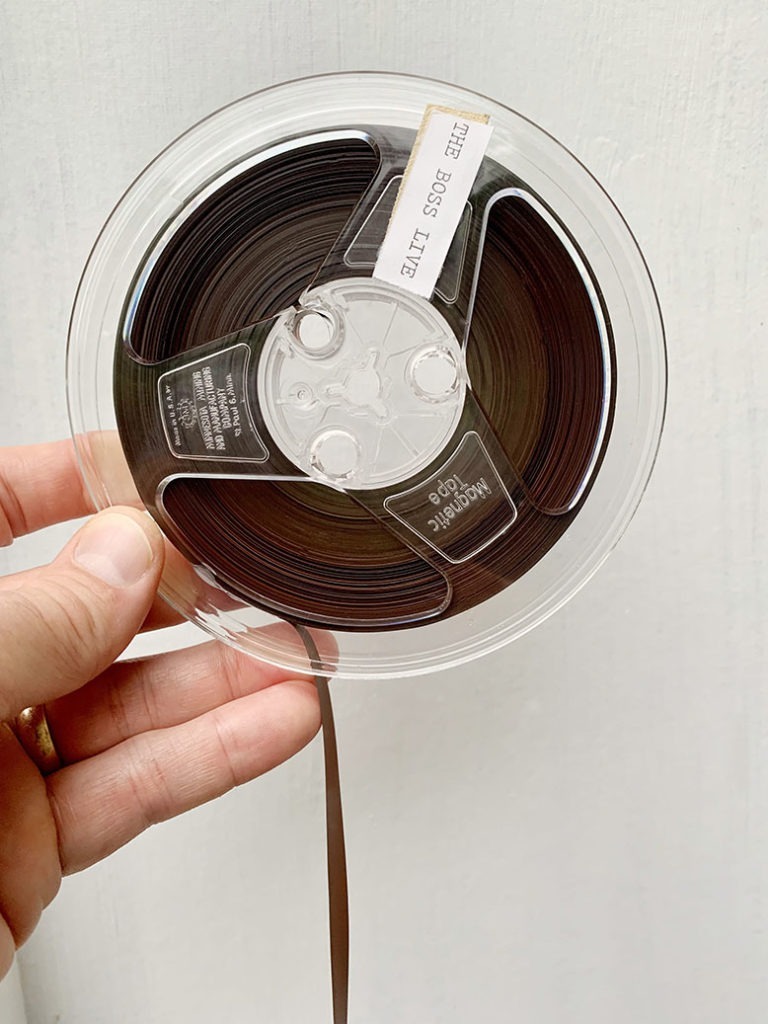

And then I found this lot of Bruce Springsteen concert tickets, which was like the jackpot—from 1980, I think, at the earliest, to the early 2000s; performances all over the place. A lot of those are worked into it. And then magnetic recording tape, which is in one of his shoulders, which I thought was kind of a cool touch.

Is sourcing found objects from places like eBay generally a big part of your process?

Generally it is. It’s very time-consuming, because you have to comb through and fine-tune your searches. I try to purchase from the top sellers, which are more reliable. When you’re finding things like autographs, you can get ripped off pretty easily on eBay, because there’s a lot of fake stuff on there. But I think I’ve gotten pretty savvy at finding my way around. I will only get something if I know it’s truly authentic. Like those photo albums—I mean, they’re yellowed, and I can’t even rip out the pages without the paper ripping, because they’ve been there since 1985. And that stuff just gives me excitement when it arrives.

So the items you stumbled upon ended up significantly dictating the final design?

For sure. Because I want them to be seen, right? They’re the most interesting, and I don’t want to cover them up. So it’s being creative in terms of how I use, for instance, the headlines, and where I position them. And making sure that some portions of the art aren’t covering up what I want people to see. And when you see the work in person, it’s a totally different experience than looking at a photograph of it.

Since you’re a Springsteen fan, did you end up using any of your own ephemera for the piece?

In my studio I have bins of old papers and maps and rope and stuff. From my cloth bin I used an old pair of jeans and just ripped them up for his jean jacket. I used things that I have here for textural integrity, things that add to it. His hair’s made of, believe it or not, farm rope—the big, thick farm rope found in hay lofts—which I soak in water. And then I spend some time fraying it apart, and then spray-paint it to kind of make it look like hair.

That hair is one of the most intriguing textural elements that shows up in many of your portraits.

Yeah, it adds a lot to a flat face, right? It kind of pulls out the whole thing. And I can’t tell you how I stumbled upon that—but I just keep doing it!

Do you prefer to take on work to which you have some emotional tie? Or, for a commission like this one, does your personal affinity for Springsteen present any specific challenges?

It does not inhibit the work. It almost adds fuel to the fire—like: I’m in this; let’s do this! I just get lit up and excited. But in life unfolding, there are stories or events happen, like the war in Ukraine. I did four pieces on that. That was not a commission; it was just my heart kind of drawing me toward the devastation that I saw. So there are those moments, too, where I’ll just start to create something out of feeling the need to get it out of myself. And then usually those things find a place in the world somewhere. Some artist friends of mine said years ago: Wayne, if you do the work that you love, in the end, chances are, many people in the world are gonna love it.

I teach combat veterans who struggle with PTSD and trauma from serving in Iraq and Afghanistan. We use art as a way to heal, and they tell their stories through visual art. And I say, Your finished work is going to emote a great depth—to the point that you give it that. If you hold back and have your hands in your pockets and you’re hesitant, your work is going to kind of limp along and not have as much impact on the general public or people that engage it. And as much as you give yourself to it and pour yourself into it, the viewers and the people engaging are going to take away that much more from it. They’re going to feel your emotion. I really, fully believe that. I’ve seen it in their work, and I’ve seen it in mine.

One of your pieces in response to Russia’s war in Ukraine features a quote by the late Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel: “Human suffering anywhere concerns men and women everywhere.” I think a lot of artists are drawn to suffering—and perhaps especially to transforming it into something else. Would you say that sensibility is a through line in your work?

Most definitely; I think so. All human beings are emotional and have feelings, but I think artists take that next step to delve into those depths and bring it out of themselves into the form of a song or book or a poem or a visual piece of art.

My emotional sense has always been high, and I like to live in that space. I don’t like the fluffity-fluff of talking about sports or the weather—which is fine, there’s a place for it—but rather: What’s goin’ on with you? And some people can’t even answer that, you know? But through art, I think there’s a way to invite people to notice things that we overlook. Art can stop you in your tracks. If you are drawn to some piece but you don’t know why, you hopefully will begin to think: What is it about this piece that I’m really drawn to, and why is that? That’s what I love.

In the case of the Bruce portrait, hopefully people begin to reflect on 9/11: Where was I? Maybe they know people who lost their lives or have firefighter relatives who were there that day. So there’s that emotional draw to the Bruce piece for sure.

How do you know when a piece is finished?

I have learned over the years that I can overwork pieces. I did that yesterday with Bruce: I have many, many other headlines from those wonderful photo books that I got off of eBay. And I was like, I gotta work in a couple more tickets. So I’m cutting tickets down and I’m cutting headlines and I’m placing them. I added a few more—nothing drastic—but then I thought, You know what? You’re pushing it, Wayne. Come on—it looks great. So I learn to listen to the instinct and just trust my gut and go, as I did yesterday: It’s done; don’t do any more to it; just be done. It’s a fine line.

I tell my students: Be connected to yourself when you’re making art, and understand that rhythm that you feel when you’re working on a piece. And trust that there are accidents that always work in your favor that sometimes make the piece better. But in order to be able to understand that, you have to be connected to yourself. I’ll use the phrase, Come back to yourself; come back to your body.Because oftentimes we walk around life just unconsciously doing what we always do, but we’re often never really connected to ourselves because we have so much shit to do. Then we get home and we’re tired, and we wonder why. But walking by flowers or trees or a certain building on the way to work and being aware and understanding that, Gosh, this is always here, and it exists like I do!—you’re connected at that point. You’re conscious.

Illustration by Wayne Brezinka

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.