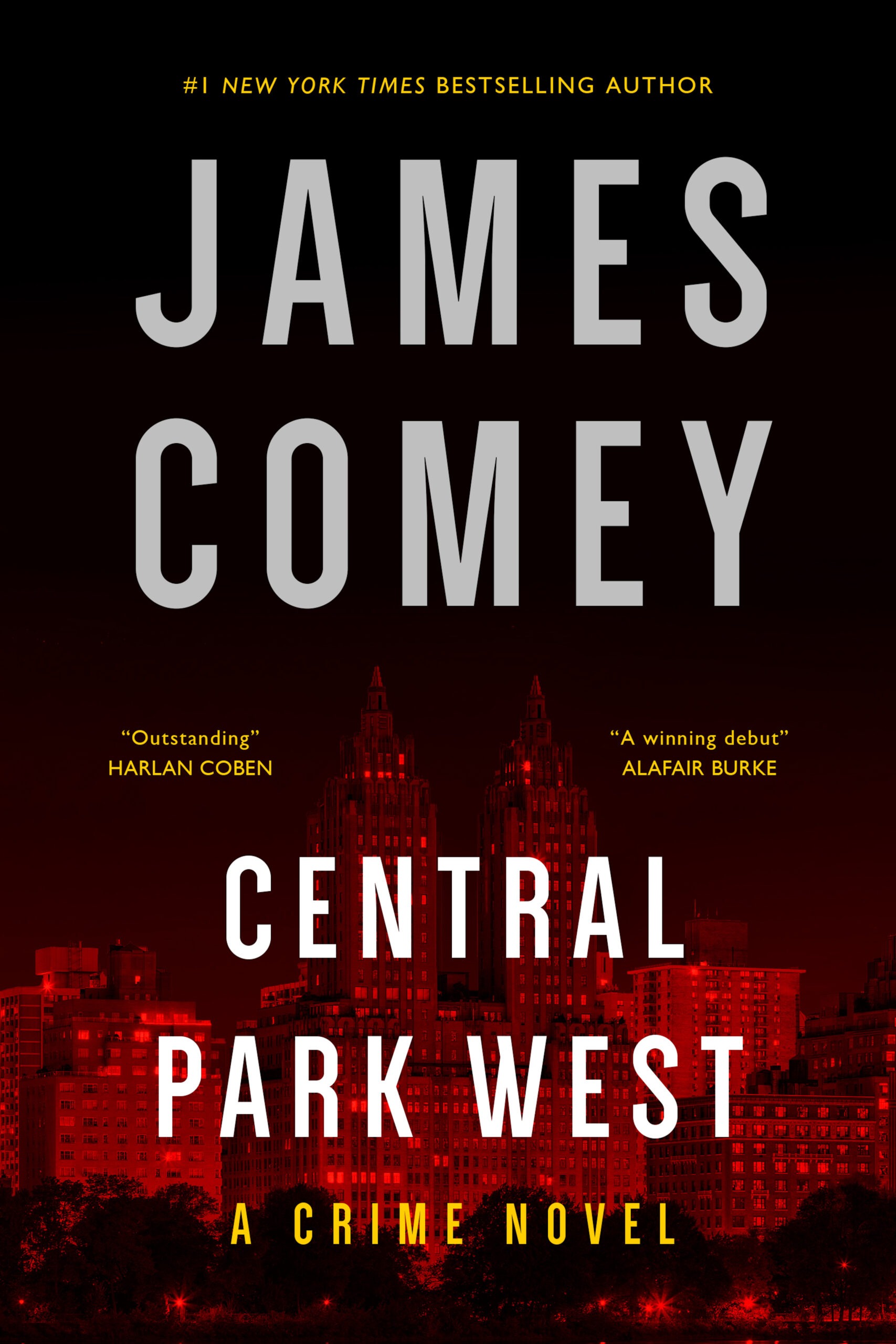

Former FBI director James Comey has taken a surprising turn with his latest project, a crime novel called Central Park West, much of which is set in his home state of New Jersey.

Comey grew up in Allendale, where, as a teenager, he was the victim of a frightening home invasion. He and his brother were held at gunpoint by a man thought to have been the Ramsey Rapist, a criminal who terrorized Bergen County in the late 1970s. For years, Comey had nightmares about the incident. (No one was ever sent to prison for the crimes.)

Comey, who raised his children in Maplewood and now lives in Virginia, went on to become a prosecutor, a U.S. attorney and a defense lawyer before joining the FBI and taking the job of director in 2013. He was fired by former President Donald Trump in 2017, prompting an investigation into Russian election interference and collusion with the Trump campaign.

His new book draws on his experience in law enforcement and the legal system, and his background in prosecuting the Mob, which figures prominently in the novel.

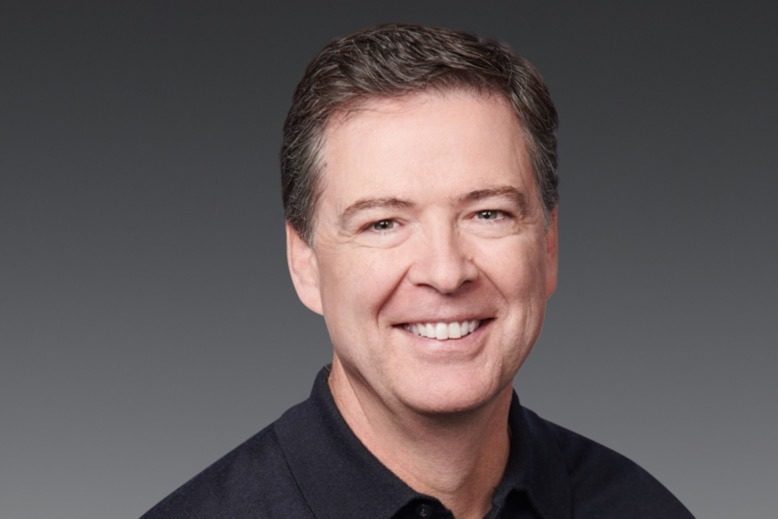

Central Park West is out now. Photo: Courtesy of James Comey

Why did you want to write a crime novel, and have you been wanting to do so for a long time?

I was first nudged by my editor from my last nonfiction book, Saving Justice, which is a set of stories from cases I did. It’s funny, he would refer to something in the book as a scene, and he would say it reads like fiction. Then he asked if I’d ever considered writing crime fiction. I said no. And then he would nudge me again. I sort of ignored it. But then I was talking to Patrice, my wife, about it, and she said, “You know, you might have more fun with it than you think,” …and then she pitched me on this story about the Mob in New York, and I started writing it and found it harder than nonfiction—but addictive. So I never expected to be here, but I’m very glad that my old editor nudged me. Because I really did enjoy it as much as he thought I might.

What is your writing schedule like?

The day began with my wife, Patrice, and I having coffee and talking about her comments on what I’d written the day before. I write on a Google doc—I learned how to type at Northern Highlands High School. She makes editorial comments like, “This doesn’t make sense,” or, “This looks good.” And then we discuss those comments. Then I go to work. Some days I run out of gas after a few hours, and some days you just get lost and look up and it’s been six or seven hours, and you didn’t eat. When the weather’s OK, I’ll sit on our back porch, or I’ll go sit in the corner of our living room and work on my laptop.

How much of your experience in law enforcement did you use in the story?

A ton of it is drawn from my experience—really in three different ways: first, as a line prosecutor in Manhattan doing Mob stuff; then, as the U.S. attorney in Manhattan after 9/11; then, as the FBI director, because it gave me insight into a lot of things that the bureau does. What I tried to do is write it as real as fiction can be. I mean, it’s still fiction, but I tried to bring people into the courtroom, into the cases, in an accurate way, so the reader will get a sense of how it really works. The people are drawn from witnesses and lawyers and colleagues I really dealt with. The character Frenchie is closely based on a real, high-end art thief who was a witness for me. One of my current editors wanted to change something about the way in which Frenchie stole a Remington from an Upper East Side gallery. And he said, “That just doesn’t seem realistic.” And I said, “Look, it actually happened that way.”

When you were a teenager growing up in Allendale, you and your brother were held at gunpoint by someone thought to have been the Ramsey Rapist. That must have been a frightening experience. Did it give you insight into how victims feel?

I was a senior in high school in the fall of ’77, which for the New York metropolitan area was the summer of the Son of Sam, when the killer was preying on people. But in Bergen, especially Northern Bergen, there was a figure who was all over the media called the Ramsey Rapist, who was a serial robber and rapist who was preying on babysitters. It was a really big deal in that area at the time. I was home one night in my family’s little ranch house in Allendale. And the police thought that this guy thought he saw my sister in the basement alone—it turned out it was actually my brother, and he obviously didn’t know that I was home. It’s a really, really scary story. [The intruder] had a ski hat on and had a gun, and he held my brother and I captive. We escaped out a bathroom window; then he caught us again. I was certain he was going to kill us. It was just a crazy, crazy night.

People used to say to me, “Thank God you weren’t hurt.” And I would say, “Yeah, we’re very lucky.” Of course I’m thinking, What does that mean? I thought about that guy every night—not most nights, every night—for five years.

I’m 62 years old, and my parents are both gone now. But when I drive past that house, I still think of it. And so it gave me, I hope, empathy for victims of crime. I hope it made me a better prosecutor [and] law enforcement person, because I could try to understand a piece of what violent crime does to innocent people.

Is that partly why you got into law enforcement?

I don’t think so. That’s what’s so odd, is I think I still wanted to be a doctor after that. But, you know, we’re all poor narrators of our past. I have to think it was something that nudged me, but I didn’t know I wanted to be in law enforcement until I went to law school. I worked in the legal aid clinic and thought, This is part of helping people that I like—just like the reason I wanted to be a doctor. And then I was struck by lightning in a courtroom in the Southern District of New York, watching the government try and detain a Mob boss. I’ve always hated bullies. And I thought, These are the biggest bullies there are. If I can be part of saving people from these people, wow. And that’s when I went home and called my girlfriend, now my wife, and said, “I know what I want do with my life.”

Your novel is set partly in Hoboken and Maplewood. What are your ties to those places?

I used to live in Hoboken for four years—first, right near 10th and Bloomfield, and then 8th and Willow. When we got married, we lived at 12th and Washington. I wanted to have Nora [the main character in the novel] live near there because I know that area really well. Then, we moved out to Maplewood.

What made you want to set your novel in those places?

They are places that I have fond memories of, and I could go there in my mind and feel it—the sidewalk and the train station. I just spent so much time in those places. Hoboken is a walking city, and I spent so much time walking around that I could imagine it in a way that I was really there, which is harder with places that I’ve never been to.

Have you started working on your next book yet?

Yes, I’ve finished the draft of the next one, and it’s in the process of “family review.” I have five kids and they’re really smart, so they read it and give me feedback. Then I’ll send it out to friends who know law enforcement. I imagine this as at least a trilogy. The next book will move the locus of action to Westport, Connecticut, to an enormous hedge fund—which I also worked at— between government stints. I was the general counsel of Lockheed Martin, the world’s largest defense contractor—so that’ll figure in future books, and then Bridgewater Associates, which is a hedge fund.

Will the next book feature the same characters?

The character of Nora will be at the center of the next book.

She’s a great character.

Yes, I can see her. It’s another thing that happens in fiction—they become real. And when someone suggests a change, your reaction is, “I can’t change that. That’s Nora.” And my wife has to say, “Dear, Nora is made up.”

Some novelists say that they sit down and the characters kind of guide the story.

It’s true. Nora is inspired by my oldest daughter [Maurene Comey], who’s a federal prosecutor in Manhattan. She prosecuted Ghislaine Maxwell and Jeffrey Epstein, until Epstein killed himself. And she prosecuted the Maxwell trial in courtroom 318. Here’s where it’s really strange. It’s the same courtroom where I prosecuted John Gambino when she was a little girl growing up in Maplewood. I wanted to go watch the trial. I was writing this book while she was doing that trial, and I wanted to go watch, but she banned me because she said, It’ll be too much of a thing.

How do you compare the pressures of working in law enforcement and being the FBI director to writing a novel?

They’re similar in the sense that your work is going to be judged by people you don’t know. And that’s true in a high-profile public job and in this. But [they’re different] in the sense that this is a lonely, almost solitary job in the way that being director of the FBI is not, because you’re surrounded by people literally all the time. You have a security team around you all the time. The job never leaves you. And that’s a different kind of pressure. It makes it much harder than being a novelist. [New Jersey author] Harlan Coben described himself to me in a way that fits me. He said, “I am a socially adept introvert.” And so am I. I can do all the public stuff, but I don’t get energy from it.

I would much rather be alone or with my family in my backyard, sitting on my porch working on something like this. So it’s easier for me in that way too. Whereas being FBI director was hard because I don’t want to be famous. I don’t want to be out there with big groups of people. I know I’m going to have to go on the road and promote this book, but that public profile for someone with my kind of personality is a lot of work, in a way that being a novelist is not.

Do people still ask you about the Hillary Clinton email investigation? Does that still come up when you talk to people?

It does sometimes. But far less as time goes by, and almost never with younger audiences. But people do. And I tell them it’s one of the biggest nightmares I’ve ever been involved in. I had two choices, and, as one of my colleagues said, there were two doors, and they both led to hell.

There was no good option for me, for us then. But now people recognize me much less, which is a good thing. Now I get, “I think I know you?”

I’ll tell you a true story from this week. I was in the supermarket just outside of Richmond, Virginia, and a lady came up to me and said, “I think I know you.” And I kind of shrugged. And she said, “I think I do.” And I said, “Well, I used to work in the government.” And she said, “No, my husband works in the government, that’s not it.” And I said, “Well, I used to be the FBI director.” And she says, “Nah, that’s not it. I’ll think of it.” And she walks away.”

No one knows New Jersey like we do. Sign up for one of our free newsletters here. Want a print magazine mailed to you? Purchase an issue from our online store.