Decked out in a black suit with a red pocket square, David Saint, artistic director for George Street Playhouse, strolls into the unfinished 23-story building towering over Livingston Avenue in New Brunswick. Except for the required hard hat, Saint might be heading to an opening-night performance rather than an infrastructure tour.

“Can you believe it? It’s amazing, right?” Saint exclaims as he surveys the steel-and-concrete bones of the 486,000-square-foot structure. Saint looks past the exposed pipes and raw surfaces to visualize what soon will be the New Brunswick Performing Arts Center.

When complete, the $172 million complex, built on the footprint of the old George Street Playhouse and Crossroads Theatre Company, will comprise two state-of-the-art theaters, three stage-size rehearsal rooms and a 207-unit residential tower with a rooftop swimming pool. The center will serve as the home for the two theater companies, as well as American Repertory Ballet and Rutgers University’s Mason Gross School of the Arts.

Merissa Buczny of Devco, David Saint of George Street, Sharon Karmazin and Dina Karmazin Elkins of the Karma Foundation, and Chris Paladino of Devco strap on hard hats and tour the facility in April.

Photo by Frank Veronsky

On September 4, after nearly two years of construction, the center will welcome invited guests for a reception, tour and mini-performances by the resident companies. Governor Phil Murphy and New Brunswick mayor Jim Cahill are expected to attend. The following day, the public will be able to take tours and experience indoor and outdoor performances. That evening, Crossroads Theatre will open its season with Paul Robeson, a play about the Rutgers-educated scholar/athlete/entertainer/activist.

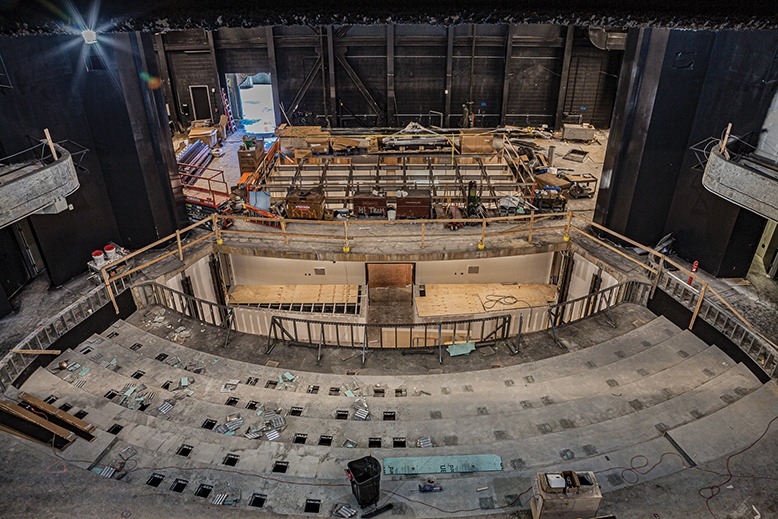

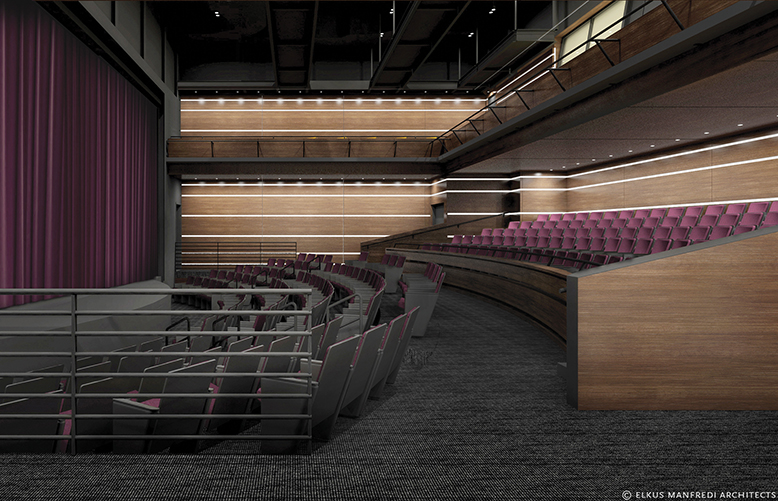

But on this early spring day, Saint takes to a podium on the stage of the Elizabeth Ross Johnson Theater, named for a George Street benefactor, and dazzles members of the media with details of the 463-seat auditorium and the adjacent Arthur Laurents Theater, named for the late Broadway playwright and director who premiered many of his works at George Street. In the months to follow, the exposed girders will become wood-paneled walls; continental seating (with no center aisle) will rise from newly finished floors; and the wooden planks at the base of the stage will reveal a bi-level, hydraulic-lift orchestra pit suited for up to 70 instrumentalists.

“For years, I’ve had this dream,” says Saint. “Today it’s finally coming true.”

The new arts center is not Saint’s dream alone. The city of New Brunswick has pondered an arts-district initiative for more than a decade. Chris Paladino, president of the urban real estate company New Brunswick Development Corporation (Devco), calls the plan “an unfinished symphony.”

That metaphor can be applied to the ongoing redevelopment of New Brunswick’s downtown. The renaissance began in the mid-1970s, when architect I.M. Pei, best known for the glass pyramid at the Louvre in Paris, unveiled a $150 million revitalization plan for New Brunswick. Around this time, construction was underway in New Brunswick on Johnson & Johnson’s world headquarters, designed by Pei’s architectural firm.

By the mid-1980s, the neglected State Theatre New Jersey, a former vaudeville/silent-film house opened in 1921, had been restored. Since then, and after an extensive multimillion dollar renovation in 2003, the State Theatre has been the anchor of the city’s cultural district.

The State Theatre acquired a new neighbor in 1984, when George Street Playhouse moved to Livingston Avenue. Other performing arts organizations followed George Street into the burgeoning arts district. In 1991, Crossroads Theatre, which had been operating in a sewing factory on Memorial Parkway, moved in next door. Eventually, the American Repertory Ballet Company, which had had a presence in New Brunswick since 1979, relocated to offices in the Crossroads Theatre building.

And so Pei’s vision was fulfilled. The architect died at the age of 102 this past May, but the city continues to expand on his plan. As Devco’s slogan—“A city is never finished”—suggests, redevelopment is an ongoing process.

“When we came on the scene,” says Anthony P. Carter, president of Crossroads Theatre’s board of trustees, “[New Brunswick’s] backdrop and landscape were very different, and the city was becoming more diverse.”

Over his nearly 22 years at George Street, Saint has seen New Brunswick’s downtown transform into “a destination city.”

George B. Stauffer, who stepped down as dean of the Mason Gross School of the Arts at the end of the school year, agrees. “When I arrived in New Brunswick in 2000, the downtown area was still largely undeveloped,” he says. “[Now], New Brunswick has come of age.”

That’s partly due to a 2007 study by Americans for the Arts, which revealed that nonprofit arts and culture organizations added $36.57 million to the local economy in fiscal year 2005. The 10 organizations that participated in the study (including the three New Brunswick PAC resident companies) served about 545,000 attendees and supported more than 800 full-time-equivalent jobs that year.

That’s partly due to a 2007 study by Americans for the Arts, which revealed that nonprofit arts and culture organizations added $36.57 million to the local economy in fiscal year 2005. The 10 organizations that participated in the study (including the three New Brunswick PAC resident companies) served about 545,000 attendees and supported more than 800 full-time-equivalent jobs that year.

The findings reinforced Mayor Cahill, who has been in office since 1991, and other stakeholders’ commitment to the arts.

“The New Brunswick Performing Arts Center…will bring even more patrons to New Brunswick to enjoy our arts houses, dine at our restaurants, and enjoy our hospitality and nightlife,” says Cahill. “We anticipate that this renewed investment in our arts district will allow for 100 additional performances per year beyond the current offerings, resulting in an anticipated additional 39,000 patron visits.”

Devco president Paladino acknowledges that some observers have questioned the wisdom of replacing two theaters with two more theaters. But, he explains, “we built two state-of-the-art theaters that are going to let us really drive the arts engine, not only in New Brunswick and the region, but the state.”

Statewide, the arts generated nearly $520 million in 2015, according to a 2017 Americans for the Arts study.

“The New Brunswick PAC is expected to generate an additional $20 million for the local and state economies,” says Paladino.

The opening of the arts center starts a new era for its resident companies and for Rutgers. For Mason Gross students, “the new center will now allow our students to work arm-in-arm with professional actors, dancers and technicians,” says Stauffer. Rutgers invested $17 million in the new facility and owns a 28 percent stake.

When former Rutgers faculty member Eric Krebs founded George Street Playhouse in 1974, a repurposed supermarket served as its performance venue. Ten years later, the company moved into a former YMCA on Livingston Avenue, where it remained until a demolition team took the building down to make way for New Brunswick PAC.

Saint says the organization’s YMCA facility was “falling apart” and had technical limitations. During performances, the orchestra was in another room, and each instrument needed a separate mic.

“This is actually the first time in our history that we’ll have a theater that’s been designed as a theater to begin with,” says Saint.

Saint and representatives from the other resident companies have worked alongside the consultants of the New Brunswick PAC. Elkus Manfredi Architects, who designed the Rutgers Academic Building on the College Avenue Campus, consulted on building design; Auerbach Pollock Friedlander, who worked on Princeton University’s Lewis Arts Complex and Judy and Arthur Zankel Hall in Carnegie Hall, was the theater-design consultant.

New Brunswick PAC is the American Repertory Ballet’s first official home. The largest dance organization in the state, ARB is celebrating its 40th season this year.

“We are proud to be a founding resident company alongside our fellow arts organizations,” says executive director Julie Diana Hench. The new facility, she adds, “enables us to increase [our] diversity of programming and community engagement.” The company will continue to take its annual Nutcracker production to other venues, including the State Theatre, but the mainstage season will be at New Brunswick PAC.

Before the new performing arts center could be built, the existing arts district had to be destroyed. When construction began on the facility in October 2017, George Street relocated to the former home of the New Jersey Museum of Agriculture on Rutgers’s Cook Campus. For Crossroads Theatre’s 2017-2018 season, the company went on the road, performing at venues around the state.

Although the State Theatre, the state’s second largest presenting theater after NJPAC in Newark, is not part of the New Brunswick PAC, it practically shares a wall with the complex. “Bringing those audiences back and really…reengaging the entire block as a cultural district is what we’re definitely looking forward to,” says Sarah Chaplin, the State Theatre’s president and CEO.

Patrons will be pleased with amenities, including a large lobby equipped with a concession stand, bar and box office; roomy bathrooms; elevators; modern temperature-control systems; and a 344-space parking garage connected via a corridor to the building.

The city of New Brunswick owns the land on which the new facility sits, but Rutgers, Middlesex County, Devco and the New Brunswick Cultural Center, an organization that works to stimulate the arts in the city, are all co-owners of the arts infrastructure. Rising above the theater complex will be 30,000 square feet of office space, owned by the county, and a residential tower with more than 200 rental units that will be ready to lease when the center opens. Eighty percent of the apartments are market rate and 20 percent are affordably priced. Pennrose Properties, the real estate developer for the units, has been working with the New York-based Actors Fund to market the affordable units to members of the arts community.

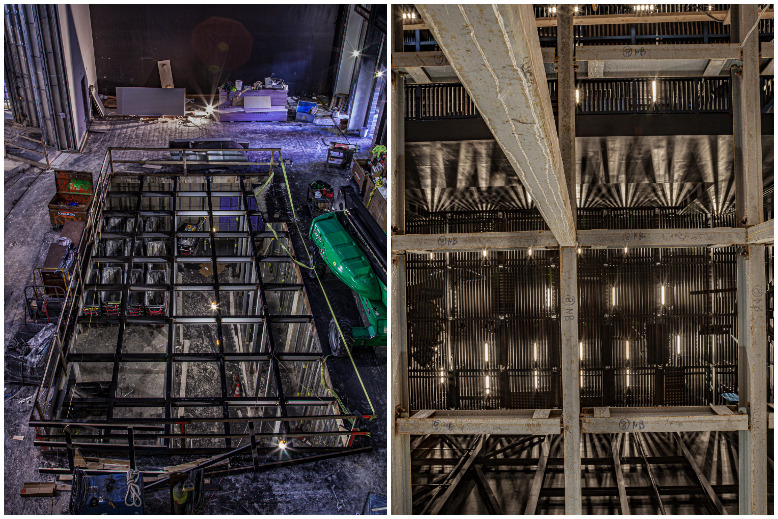

From left: Looking down into the trap room, the chamber under the stage, of the Elizabeth Ross Johnson Theater; looking up at the 75-foot-high fly tower used for hoisting scenery and props. Photos by Frank Veronsky

The new facility is designed to accommodate various types of performances. The three rehearsal rooms with floor-to-ceiling windows look out on the Heldrich Hotel. With sprung flooring designed to absorb shock, two rooms are the size of the Arthur Laurents stage; the third matches the dimensions of the Elizabeth Ross Johnson stage. One will double as the donor lounge during performances.

The 72-foot-wide Elizabeth Ross Johnson stage will mostly be used for musicals and dance performances. A 75-foot-high fly tower is positioned above the stage for hoisting scenery and props. The sprung floor is divided into 4-foot-by-4-foot removable sections. The wings are designed to accommodate large sets. The catwalks have fall-protection systems for the safety of lighting technicians.

The Arthur Laurents Theater has 252 seats and a 60-foot-wide stage—ideal for more intimate plays.

That’s what Jeffrey Seller, the Broadway producer for Rent and Hamilton, loved about the facility when Saint showed him the renderings. “[He] just looked me in the eye and got sort of teary and said, ‘This is extraordinary,’” recalls Saint. “‘You’ve got the intimacy…but you’ve got all the technical requirements to do a first-class Broadway production.’” Saint says producers have already contacted him about trying out shows in New Brunswick, rather than Chicago or Boston, before moving them to Broadway.

Saint wishes Laurents, his mentor and good friend, had lived to see the facility. (Laurents died in 2011 at the age of 93.) “He’d always talked about the fact that George Street was his artistic home,” says Saint. The duo worked together on the 2009 Broadway revival of West Side Story. Laurents was director and Saint was associate director. Now, Saint is the literary executor of Laurents’s estate and the president of the Laurents/Hatcher Foundation.

A rendering of the entire 23-story building, courtesy of Elkus Manfredi Architects.

“He left a legacy gift for George Street in his will,” says Saint. “Every year, we get funds from his estate to support [our] work.”

George Street is known for producing original plays. “New work is the blood of the American Theater,” says Saint. “You need to have your transfusion every once in a while.”

Similarly, Crossroads Theatre, established in 1978 by Rutgers alumni Ricardo Khan and L. Kenneth Richardson, focuses on new works, specifically about the African-American experience.

From its inception, “Crossroads was a beacon lighting the way, illuminating stories of the African diaspora,” says Carter. “That is the core of our DNA and our legacy.”

“As a resident member company of NBPAC,” he adds, “we get to help usher in a new era of arts and culture for our city. Crossroads is, and will continue to be, the nexus, the connection between people, cultures, places, ideas and conversations.”

And stimulating conversations unite people. When talking about New Brunswick’s soon-to-be reinvigorated cultural arts district, Saint is reminded of what producer/director Joseph Papp used to say when they worked together at the New York Shakespeare Festival (now Shakespeare in the Park): “Theaters are like grapes. They grow better in bunches.”

“It’s true,” Saint continues. “When you have a shared lobby, and you have different works, audience members can say, ‘Oh, we’re seeing this show in this theater.’ And, ‘Oh, I saw that last week, we’re going to this one tonight.’ That kind of excitement is contagious.”