Every June, Meredith O’Brien’s family piled into the station wagon and drove from their home in Westchester County, New York, to their house in Avon-by-the-Sea. All summer, O’Brien played with friends, sharing french fries at Avon Pavilion and buying candy on the boardwalk.

But by her early teens, O’Brien was no longer carefree. “I ate so much today,” she wrote in her diary. “This week, I will go on a diet… I have to look good in a bathing suit. I need to be skinny…talking major diet…”

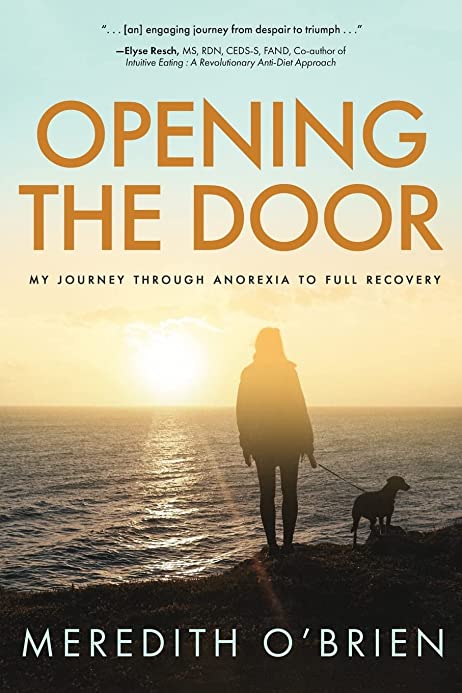

O’Brien’s memoir came out this summer.

At 35, O’Brien sought treatment for anorexia. The process dominated her life for more than a decade. She also suffered from alcoholism. Now 48, a social worker and counselor, she lives in Fair Haven and runs a private practice in Red Bank focused on eating disorders. She has been in what she describes as “full recovery” from anorexia for four years and has been sober for a decade. This summer, Koehler Books published her memoir, Opening the Door: My Journey Through Anorexia to Full Recovery.”

It is a timely topic. The Centers for Disease Control has found that the proportion of emergency room visits for eating disorders doubled among adolescent females during the pandemic. The help line of the National Eating Disorders Association saw a 107 percent jump in calls, texts and messages from March 2020 to October 2021. O’Brien says eating disorders can be a response to stress in a chaotic time. “It gives you a sense of control.”

Although eating disorders are commonly associated with teenage girls, the conditions can emerge at any age. Men and boys can suffer from it, though women and girls are twice as likely to have an eating disorder, according to the Harvard-based organization Strategic Training Initiative for the Prevention of Eating Disorders (STRIPED). Nine percent of New Jerseyans will have an eating disorder at some point in their lives, according to research by STRIPED, which also determined that, nationally, 10,200 people die each year as a direct result of an eating disorder.

O’Brien’s self-consciousness and anxiety worsened in her teens. She began to severely restrict the amount of food she ate. She forced herself to vomit after meals. When her parents and friends questioned her, she denied anything was wrong. Kristen Murphy, a summer friend from Avon since the age of six, says the disorder had an impact on their friendship. “I’d say, ‘Let’s go to the movies,’ and she’d be like, ‘I need to go to the gym first.’”

Murphy remembers going out to dinner with O’Brien at the Draughting Table in Bradley Beach when they were teens and watching her friend push her food around on the plate. “I didn’t understand why she wasn’t eating,” Murphy says. “She never had an answer for it, or she downplayed it, saying, ‘It’s not that big of a deal, I just want to stay thin.’”

Years later, O’Brien’s friends understand it was a big deal, and not easy to solve. “As a young person, I didn’t have an appreciation for why she couldn’t enjoy a plate of nachos with the rest of us,” says Madonna Davidson, another summer friend. “It’s much deeper than food.”

In O’Brien’s case, multiple factors contributed, including a family history of eating disorders and anxiety, as well as her own obsessive perfectionism. Moreover, O’Brien was traumatized at 13, when she was raped by a friend and hid the assault from everyone. “Inside, I was crumbling,” she says. Restricting food intake and purging what she did eat gave her a false sense of control and became a comforting ritual, while chipping away at her self-esteem. Her mind raced with self-destructive chatter: You have no willpower. You are going to get fat. You are absolutely not normal.

Eating disorders, O’Brien came to realize, can be exacerbated by unrealistic beauty ideals and ruthless marketing campaigns. “Diet culture is one big lie,” she says. “I truly believe people who recover from eating disorders have a better relationship with food because we remove social media, we don’t read magazine articles about losing weight, and we disentangle morality from food. We are bombarded with the diet culture. I don’t want to change my body anymore because I don’t buy into it anymore.”

In January, Assemblyman Thomas P. Giblin (D-Montclair), Assemblywoman Britnee N. Timberlake (D-East Orange) and Assemblywoman Valerie Vainieri Huttle (D-Englewood) cosponsored a bill to designate the last week in February as Eating Disorders Awareness Week. The bill has not been heard, but has been referred to the Assembly Health Committee, according to Timberlake’s office. O’Brien’s friends say more awareness can be a great help to people with eating disorders and those who care about them. “It’s a challenge to know how to lend support,” Davidson says. “I think it’s a very isolating condition.”

O’Brien says her recovery has brought her a sense of “food freedom” that has allowed her to shake off an isolating, secretive approach to life. “Food is the way we connect with other people and celebrate,” she says. “My eating disorder took up so much of my life and took away that ability to connect with my friends. Now I look forward to sharing a pizza with them.

“I wanted to share with people that you can have anorexia for 25 years and still recover,” she adds. “You’re not alone. You’re not the only 40-year-old, middle-aged woman struggling with it.”