The city intends to exercise eminent domain to raze what remains of the block that includes Memphis Lee’s cozy cafe. Memphis owns the dilapidated building that houses the beloved little eatery, and the plot springs into motion on his determination to make the city meet his price of $25,000. His customers assure him he’ll never get more than $15,000, if that, and he better wise up.

But Memphis isn’t the only one wrestling with the question of worth. Holloway (James A. Williams), a codger with a philosophical streak, hoots at the white idea that blacks are lazy, pointing out that they toiled day and night as slaves for hundreds of years, and now that the white man is obliged to pay them, suddenly there’s no jobs.

Holloway is funny, a bit of a sage and a secular preacher. The undertaker West (Harvy Blanks) has his own calculation of how much his fellow blacks are worth, and selling them expensive caskets and "laying them out in style" has made him the richest man in the neighborhood.

Hambone (Anthony Chisholm) too knows what his work is worth. In fact, it is the only thing on his mind. Or what’s left of his mind. He’s scary, damaged and pathetic, a traumatized soul.

Issuing an animalistic roar, Hambone staggers into the cafe (and the play) in the middle of the first act. He has by far the fewest lines of any of the seven characters. But you will not forget them. Or him. Bearded and bearlike, he spends much of his time onstage on a stool at the counter, bent silently over a bowl of beans. From time to time he erupts into ferocious, rumbling screams of "I want my ham! He gonna give me my ham!"

Sheer madness? Holloway proposes that Hambone may have "more sense than the rest of us." How? Ten years earlier, Hambone agreed to paint a fence for Lutz, the white butcher whose shop is across the street from the cafe. If the work was satisfactory, Lutz would pay him with a ham. But when the fence was painted, Lutz deemed the job unsatisfactory, and offered a chicken instead. Take it or leave it.

Hambone left it. But every single morning since that day he has gone back to Lutz to demand his ham. It has driven him mad, but Holloway’s point is that accepting less than your due poisons the soul.

A biographical origin of Hambone’s stubbornness is suggested in The Cambridge Companion to August Wilson, edited by Christopher Bigsby. In an illuminating essay in the book, New Yorker theater critic John Lahr notes that in 1955, when Wilson was growing up in Pittsburgh, his mother, Daisy, correctly answered a question on a radio quiz show. The prize: a new washing machine, which she, as a single mother of six, could sorely use.

But, Lahr relates, when the promoters found out she was black, they gave her a Salvation Army gift certificate instead, and told her to pick out a used machine there. She refused.

A friend urged Daisy to settle for the used machine. Wilson told Lahr, "And my mother said, ‘Something is not always better than nothing.’"

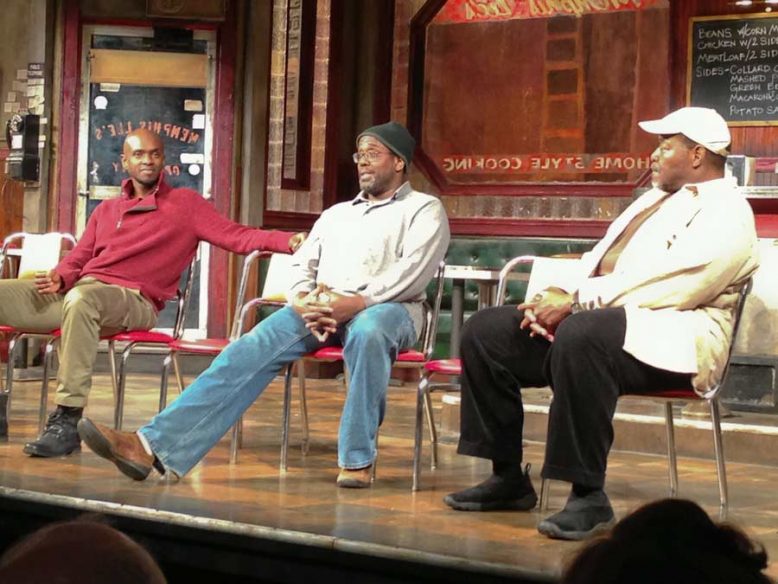

Many layers of meaning unfold in this play. Director Ruben Santiago-Hudson (A Wilson veteran with Tony and Obie awards to his credit) orchestrates the physical and emotional rhythms of the piece so they become inseparable from the irresistible music of Wilson’s language. Funny, sad, wise, challenging, the words fly by with such speed and naturalness that, during the post-performance discussion with the cast, an audience member asked if some were improvised.

The actors suppressed a chuckle. Absolutely not, Chuck Cooper (Memphis) assured him. In every one of the 10 plays that make up Wilson’s epic "Twentieth Century Cycle"–each play set in a different decade, "Two Trains Running" being the seventh–every single word is so rich with purpose that the cast aims, Cooper said, for nothing less than "letter perfect."

"August Wilson," Cooper added, "teaches us all the time."

That idea gives an intriguing twist to a key point Lahr makes in his essay:

"For white members of the audience," Lahr writes, "the experience of watching a Wilson work is often educational and humanizing. It’s the eternal things in Wilson’s dramas–the arguments between fathers and sons, the longing for redemption, the dreams of winning, and the fear of losing–that reach across the footlights and link the black world to the white one, from which it is so profoundly separated and by which it is so profoundly defined.

"To the black world, Wilson’s plays are witness; to the white world, they are news."

Whether truths like Wilson’s come as alerts or affirmations, they are, like those in all great art, inexhaustible.