Explore the Garden State’s history—from the creation of the Jersey jughandle to the birth of the blueberry business and South Jersey’s Underground Railroad.

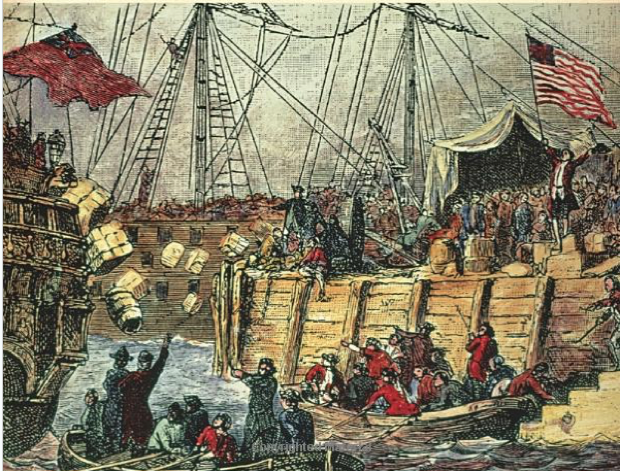

Courtesy of publisher of “Ten Tea Parties: Patriotic Protests That History Forgot”

Jersey’s Tea Party

On December 22, 1774, a feisty group of South Jersey patriots burned a load of British tea bound for Philadelphia. Among them was a future governor, Richard Howell, namesake of the Monmouth County township of Howell. The New Jersey upstarts were a little slow to get into the rebellion act. Their tea party – a protest against British tyranny—came one year and six days after the more famous Boston Tea Party. Oh well, news travelled slow in pre-revolutionary America.

“Washington Crossing the Delaware” by Emanuel Leutze.

Alexander Hamilton

The famed patriot might be making a lot of noise on Broadway these days, but in his own lifetime most of his exploits took place in his adopted state, New Jersey. The immigrant Hamilton attended school in Elizabeth and lived as a teen in Liberty Hall, now a museum on the campus of Kean University. As a captain in the Continental Army, he crossed the Delaware with George Washington and engaged the enemy at Trenton. When Washington wintered in Morristown, Hamilton was his trusted aide-de-camp. In 1778, Hamilton fought valiantly at the Battle of Monmouth and was promoted to lieutenant colonel. After the war, as Washington’s Secretary of the Treasury, Hamilton established Paterson as America’s first planned industrial city. Alas, in 1804, Hamilton suffered a fatal wound in his famous duel in Weehawken with longtime political foe Aaron Burr.

Photo by Kathy Moore

The Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was an informal network of safe houses for African-Americans fleeing bondage in the decades before the Civil War. South Jersey was a major stop along the way, with numerous clandestine destinations for the runaway slaves. South Jersey abolitionists, including Harriet Tubman, herself a fugitive from slavery, operated the secret routes and safe houses. From South Jersey, the freed slaves were led north to cross the Hudson River into New York and continue their trek, some traveling all the way to Canada.

Photo by Marc Steiner

Palisades Preservation

It’s hard to believe, but the awesome Palisades cliffs along the Hudson River in Northern New Jersey were once on their way to being blasted into gravel by quarry operators. Only the late-19th century lobbying of visionary groups like the New Jersey State Federation of Women’s Clubs convinced the legislatures of New Jersey and New York to protect the Palisades. In 1900, governors Foster M. Voorhees of New Jersey and Theodore Roosevelt of New York (the future president and creator of the National Parks System) formed the Palisades Interstate Park Commission. Armed with a $125,000 donation from banker/philanthropist J.P. Morgan, the commission secured an option to buy the largest of the quarries, which it eventually shut down.

Roll Cameras

Speaking of the Palisades, those noble rock outcroppings gave rise to the term “cliffhanger,” coined when the actress Pearl White was filmed dangling precariously over the cliffs in “The Perils of Pauline,” an early series of silent films shot in Fort Lee, the pre-Hollywood capital of America’s film business. Jersey’s film biz dates to 1893, when Thomas Edison built the world’s first movie studio, Black Maria, in West Orange. Today, the state is better known for the Jersey-bred stars it has sent to Hollywood, including Meryl Streep, Jack Nicholson, Susan Sarandon, Danny DeVito, James Gandolfini, Tom Cruise, Anne Hathaway, Queen Latifah and Ethan Hawke.

Photo courtesy of The Whitesbog Preservation Trust.

Something Blue

Elizabeth White is hardly a marquee name—but she should be. The daughter of a South Jersey cranberry farmer, White had a knack for scientific research. Working with botanist Frederick V. Coville, she tested hundreds of blueberry bushes growing wild in the Jersey Pine Barrens until she found the perfect varieties to cultivate and market. In 1916, White grew the first commercial blueberry crop, giving birth to the modern blueberry business.

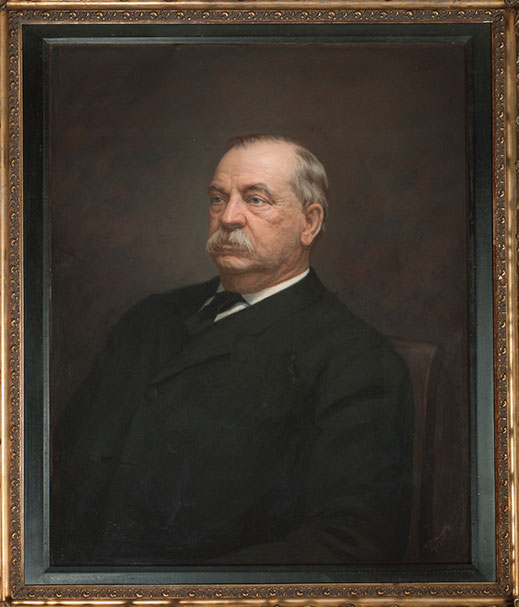

Jersey Presidents

Depending on how you count it, there have been one or two. Caldwell native Grover Cleveland, who served non-consecutive terms as president number 22 and 24, is the only chief exec born in New Jersey. Woodrow Wilson, the 28th president, is a native Virginian, but served as president of Princeton University and governor of New Jersey. And then there’s Long Branch native Garret Hobart, who served as vice president during President William McKinley’s first term. Hobart died in office in 1899. Theodore Roosevelt replaced Hobart on the Republican ticket in 1900, and ascended to the presidency the following year upon McKinley’s assassination. Undoubtedly, that opportunity would have gone to Hobart had fate not stepped in.

Photo by Stu Rosner

So Much Jazz

New Jersey can hardly claim to be the birthplace of jazz, but the Garden State has been fertile ground for jazz artists, most prominently Count Basie, who was born in Red Bank and cut his musical teeth playing up and down the Jersey Shore. Other Jersey-bred jazz greats include Newark-born vocalist Sarah Vaughan and saxophonist Wayne Shorter—not to mention Hoboken’s Frank Sinatra. Sax player James Moody and be-bop trumpeter Woody Shaw were Jersey transplants, and giants like Duke Ellington, Lionel Hampton and Billie Holiday were frequent guests on the Jersey scene during the big-band era. The state’s jazz legacy continues today with resident artists like Christian McBride and Dave Stryker.

Photo courtesy of Flickr Creative Commons: Takahiro Kyono.

Rocking the House

Can you say Bruce Springsteen? The Boss, of course, is the biggest name on the Jersey rock scene, but let’s not spare the applause for Jon Bon Jovi and his band, as well as such Jersey Shore contemporaries as Steven Van Zandt and Southside Johnny. Other names to be reckoned with from Jersey’s rock, pop and R&B past include the Four Seasons, the Shirelles, Dionne Warwick, Whitney Houston, Joe Walsh and Tommy James.

Illustration by Peter Oumanski

The Jersey Jughandle

Only in New Jersey do you have to turn right to turn left. The jughandle turn was introduced on Jersey roadways in the 1930s and today is as much a part of the Garden State as full-service gas. Our sources tell us there are more than 600 jughandle turns in New Jersey—the most of any state. You say you can’t figure out how to navigate a jughandle? Fuhgeddaboudit. You must be from Pennsylvania or something.

Photos by Axel Dupeux

Immigration

For more than a century, immigrants have been the lifeblood of New Jersey, enriching our culture, shaping our politics, seasoning our food and expanding our labor force. Today, immigrants represent 20 percent of our population—a ratio surpassed only in California and New York. New Jersey’s foreign-born population is extraordinarily varied, as illustrated by the top five countries of origin as of 2015: 12.5 percent Indian, 8.4 percent Dominican, 6 percent Mexican, 4.5 percent Filipino and 4 percent Korean.

Photo by Joe Polillio

The Jersey Shore

That would be the place with all the sand—not the TV show. The Shore stretches more than 130 miles across four counties. Vacationers started coming to the Jersey Shore in the 19th century, bound for early resorts like Cape May and Atlantic City—home of the original Boardwalk, first constructed in 1870. Long Branch was another popular early Shore destination, most notably among U.S. presidents. Seven of them vacationed in Long Branch, from Ulysses Grant to Woodrow Wilson; sadly, James Garfield died in Long Branch, where he was taken by private train in September 1881 to recover from an assassin’s bullet. The Shore has weathered changing demographics, violent storms and even reality television, but it remains everyone’s favorite reason to love New Jersey.

Comments (1)