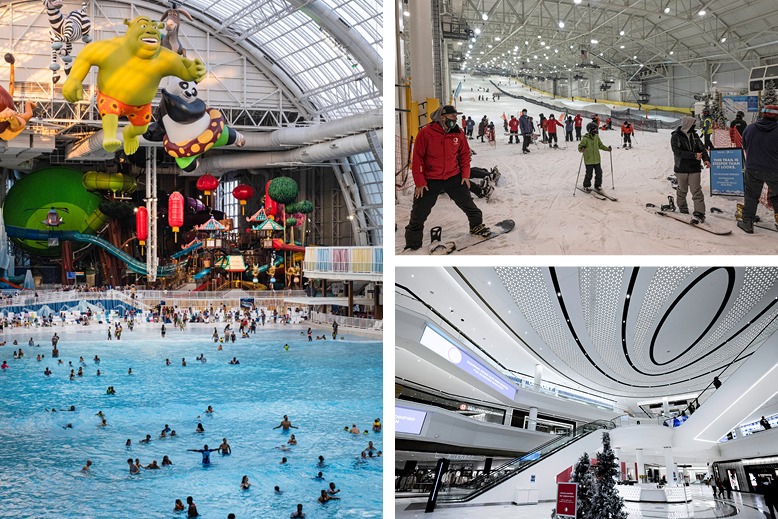

Left: In November, American Dream’s football field-sized pool at the sun-filled DreamWorks Water Park provided swimmers with a flashback to summer, while the 800-foot ski run at the neighboring Big Snow (top right) previewed winter days to come. Bottom right: Lengthy shopping corridors intersect at bright and elegant atriums, where escalators whisk visitors up to even more shopping floors. Photos by Jay Seldin

The first thing you notice about American Dream, the $5 billion megamall and entertainment complex next to MetLife Stadium that has been under construction for 17 years, is how it gleams. Everything is shiny and new.

On the outside, elegant white walls have replaced the much-maligned multicolored checkerboard paneling that repelled passersby and a governor years ago. Inside, the long, wide corridors in the four-story, 2.9 million-square-foot building are bright and seamless, expanding at intervals into massive atriums with swooping escalators. Walls of colorful graphics disguise spaces that are under construction or without a tenant.

The complex is only partially open amid the pandemic, but on a Saturday afternoon in November, about 70 skiers and snowboarders were waiting for the ski lift at Big Snow, the 800-foot-long indoor ski hill where the temperature was 23 degrees. Richie Ramos of Staten Island, equipped with snow suit, goggles, gloves and a well-worn snowboard, was trying out the jumps and rails that invite snowboarders to perform tricks on the way down. Would he come back? “Oh, yeah.”

At the neighboring DreamWorks Water Park, the temperature soars to 81 degrees and the air smells of chlorine. Here, scores of people in bathing suits and flip-flops were enjoying the waves in a pool the size of a football field. Others soared overhead on the water-propelled roller coaster that travels the perimeter of the domed enclosure. Still more plunged down a 142-foot-long slide. Some relaxed in the luxury cabanas that line the pool.

“It’s our first time here, and so far, we’re blown away,” said Jason Telesford of Piscataway, who was visiting with a group of 15 friends and family. “It’s almost like they recreated the tropics.”

The clerks at some stores looked lonely and bored, though Primark, the fashionable Irish clothing store, was busy. Gelene Reyes of Clifton was on the line outside the store, waiting to get in. “It’s our fourth time here,” she said. “I feel like you could do everything here. You don’t have to leave the mall to do anything else.”

That would seem to be a formula for success, but success has been elusive for American Dream. The project has been battered by delays, rising costs, the Great Recession, and now, a pandemic. Two successive developers failed after pouring $2 billion into what was originally called Xanadu. The current developer, Triple Five Group, the Canadian conglomerate owned by the Ghermezian family, rebranded the complex as American Dream, boosted its size by a million square feet, and has spent $3 billion since 2011.

“It’s a very expensive venture and it opened at the exact wrong time,” says Neil Saunders, managing director of GlobalData Retail, a research firm. “American Dream needs to do very big numbers to be financially successful. If the pandemic lingers, it could blow American Dream a long way off their numbers. American Dream has to fight very hard for its share of the consumer’s wallet. That’ll be the difference between it being a success or a bit of a white elephant.”

Photo by Jay Seldin

Like the operators of the nation’s 1,100 other malls, Triple Five has to contend with a seismic shift in retailing as sales increasingly migrate from department stores to online shopping, knocking a long line of retailers into bankruptcy. Then there’s the matter of limited hours and capacity reduced to 25 percent because of coronavirus restrictions. Finally, a significant portion of the complex is still not open. And, of course, there are Bergen County’s blue laws, which ban retail sales on Sunday.

Don Ghermezian, co-CEO of American Dream, is unfazed by the challenges and projections by analysts that hundreds of malls will close over the next two years.

“It’s going to get worse,” Ghermezian acknowledges during a fast-moving tour of American Dream. “We positioned this property to be the last man standing. We are currently providing an all-encompassing experience that does not exist anywhere else in the world. At the end of the day, people are going to need to get out. There will be a vaccine. We [will] generate traffic for retailers with the entertainment we provide.”

What makes American Dream different, he says, is that 55 percent of the complex is dedicated to entertainment: the water park, the ski hill, miniature golf, an aquarium, movie theaters, an amusement park, live entertainment, roller coasters and an observation wheel.

But the remaining 45 percent of the complex, 1.3 million square feet devoted to shops, is still a sizable mall by anyone’s reckoning. The staggered opening and a lack of tourism—a major component of American Dream’s business plan—have made it hard to reach the project’s revenue projections for the first year. Like other mall operators, Triple Five is negotiating with its lenders, Ghermezian says. American Dream has also fallen behind on hundreds of thousands of dollars in payments to its landlord, the New Jersey Sports and Exposition Authority (NJSEA).

The fate of American Dream will not play out in a vacuum. The Ghermezians consider American Dream the model for “experiential centers”—the next generation of shopping malls. Even as retail analysts predict that 15–25 percent of the nation’s existing malls will close over the next two years, the Dream could reshape the American leisure landscape.

If it fails, however, New Jersey, which has invested heavily in the project, could suffer a heavy blow. The complex was originally promoted as an economic development that would create jobs and cost taxpayers nothing. But after the first two developers failed, Governor Chris Christie in 2011 agreed to provide $350 million in direct subsidies, over $1 billion in cheap financing and $100 million in road improvements.

“The project is snake bit,” says George R. Zoffinger, who was president of the NJSEA in 2003 when Xanadu got underway. “First, a real estate debacle took place with the Great Recession. Then, through no fault of their own, the pandemic hits. Worst luck in the world for a project.”

***

American Dream is located eight miles west of Times Square, at the crossroads of the New Jersey Turnpike and routes 3, 17 and 120, mostly on land owned by the NJSEA.

The Meadowlands Sports Complex, comprising a football stadium, sports arena and racetrack, was in disarray in 2002, when Governor James E. McGreevey appointed Zoffinger president of the NJSEA. His job was to straighten out the mess. The Devils hockey team and the Nets basketball team were ready to flee the arena for new homes elsewhere. Attendance at the racetrack, which had once generated so much revenue that it covered the debts on the stadium and the arena, had fallen sharply.

As a result, the state was pouring millions of dollars a year into the complex to cover the debt and operating expenses. The NJSEA was losing $80,000 on every Devils game and $31,000 on every Nets game, while the stadium still had $150 million in debt 26 years after it was built.

In addition to cutting the full-time staff and ending over-the-top freebies for managers, Zoffinger and the authority solicited bids to develop a destination entertainment center wrapping around the arena, which they hoped would generate more economic activity, tourism and tax revenue.

Zoffinger has told this reporter in interviews over the past decade that the NJSEA thought it had come up with a perfect solution, one that would not cause taxpayers additional pain.

The authority selected the Mills Corp. and a partner over rival developers, including Triple Five, to undertake the $1.2 billion project. The vision included an indoor ski facility, an aquarium, a Ferris wheel, a minor league baseball stadium, and eventually, a hotel and office space. Rather than a megamall that might drain customers from the Garden State Plaza and other nearby malls, officials said, the 4.8 million-square-foot development would only have 600,000 square feet of retail.

Under the terms of the deal, Mills Corp. was required to make an initial $160 million lump-sum payment to cover the first 15 years of the lease, which it did.

“We got $160 million in cash up front, which can be used to eliminate the debt on the arena,” a gleeful Zoffinger told reporters at the time. “And we will get $65 million to fund a program for offsite roadway and infrastructure improvements.”

But the Xanadu project quickly turned into Xanadon’t.

Lawsuits brought by opponents slowed progress. Only a handful of tenants signed leases. Costs swelled. Finally, Mills Corp., which had borrowed heavily during the debt-fueled real estate boom in the early 2000s, ran out of money. In November 2006, Mills turned the project over to Colony Capital and Dune Capital (a company founded by Steven Mnuchin, who later would serve as Treasury Secretary during the Trump Administration).

Three years later in 2009, Colony and Dune also ran out of money. Construction came to a halt. More than $2 billion had been spent, but Xanadu was still unfinished.

After taking office as governor in 2010, Christie initially viewed Xanadu as a “failed business model,” pronouncing the checkerboard complex to be “the ugliest damn building in New Jersey and maybe America.” Soon, however, Christie was working with lenders to salvage Xanadu. For more than six months in 2010, lenders and state officials negotiated with Steve Ross of Related Companies, the most prolific developer in New York City, to take over, with promises to “rename, rebrand and re-skin” Xanadu.

Following ultimately fruitless negotiations in 2010 with Related Companies, the lenders held what’s known in the trade as a beauty pageant, with a half dozen developers competing for the property, including a joint venture comprised of Donald Trump and a private equity firm.

Triple Five, which already owned the two largest malls in the Western Hemisphere—Mall of America in Bloomington, Minnesota, and the West Edmonton Mall in Canada—won, signing a formal agreement in May 2011 to take over the project. The Christie administration, which had originally regarded Xanadu with such disdain, agreed to provide American Dream with enough tax breaks and other assistance to make it the largest publicly subsidized development in state history.

“It should be a viable business all on its own,” Zoffinger told me. “The overriding principle of the Xanadu project was, no taxpayer money. They wanted to pay us up front because we wanted to protect ourselves.”

Christie proclaimed that American Dream would open in time for the 2014 Super Bowl—to be held next door at MetLife Stadium—a boast that left Triple Five executives cringing. Another unrealistic opening date would not inspire confidence in American Dream’s viability, they told me at the time.

***

Triple Five’s plan was to build a complex that went beyond anything anyone had done before. Instead of the 80/20 mix of retail and entertainment at Mall of America and West Edmonton, Triple Five devoted more than half of the space at American Dream to entertainment. The company took a modular approach to the complex; if one pod didn’t work, Triple Five would replace it with something that did.

Triple Five bought an adjacent 22-acre parcel for the theme park and the water park attractions. Their design ensured that visitors would have to walk through the mall to get to the attractions, presumably sparking retail sales along the way. Patrons who registered online for the ski run or other attractions would get coupons and notices on their phones for the stores in the mall.

Jeff Tittel of the New Jersey Sierra Club, a longtime critic of the project, has argued repeatedly over the years that it would contribute to gridlock and pollution at an already congested crossroads in the Meadowlands. “I think American Dream is really a nightmare,” he says. “It’s the wrong project at the wrong place at the wrong time.”

The project always faced formidable challenges. There is no shortage of malls in New Jersey, including six within a 50-mile radius of American Dream. Blue laws bar retail sales on Sundays at the complex. And at least 20 times a year, the Jets or Giants have a football game next door, leaving fans to fight for parking. Some analysts have also been skeptical that American Dream could siphon millions of tourists from New York City, a theme park unto itself with just about every imaginable retailer.

Still, American Dream ground forward in fits and starts, with Triple Five gutting the existing interior, putting a new skin on the exterior, and making plans for at least a partial opening in the fall of 2019.

If fully operational, American Dream is projected to employ 16,000 people and generate $1.2 billion in revenue annually, as well as $148 million a year in state taxes.

Ghermezian told Bloomberg Businessweek four years ago that American Dream’s mix of entertainment attractions, restaurants, theaters, shops and department stores was “Internet-proof.” Even the retailers, he claimed, would be immune from the turmoil coursing through their industry as consumers increasingly turned to their computers to buy everything from clothing to books to fire pits.

But no one imagined the kind of havoc a pandemic would wreak in 2020, which only accelerated the migration of shopping from storefronts to the Internet. E-commerce accounted for nearly 20 percent of all retail sales in the United States during the first nine months of 2020, up from 15 percent in 2019, according to figures from the U.S. Commerce Department.

In the past two years, a staggering number of department stores and other shopping-mall stalwarts have stumbled into bankruptcy court, including Steinmart, J.C. Penney, Payless ShoeSource, Gymboree, Ann Taylor, Lane Bryant, Le Pain Quotidien, Lucky Brand Jeans, New York & Co., Sur La Table, Muji, Pier 1 and Neiman Marcus.

Retailers announced plans last year to close more than 10,600 stores nationwide. In May 2020, Credit Suisse analysts estimated that as many as 25 percent of the country’s 1,100 malls would close by the end of 2022. “Some malls will exit completely,” Neil Saunders of GlobalData said. “There’s no use for them.”

More recently, some of the companies that were to anchor American Dream dropped out, including Lord & Taylor and Saks Off 5th. Toys R Us and FAO Schwarz backed out of their planned three-level, 60,000-square-foot shared flagship. And after Century 21 started building its 57,000-square-foot store on the second level of American Dream, the company filed for bankruptcy protection and shut down. In November, a sign was still visible through its window: “Designer Brands Up to 65% Off Every Day.”

Six other Dream retailers, including Barney’s New York, Garage and GNC, also filed for bankruptcy protection and fell out of the mix.

Some were to be large stores, collectively accounting for a sizable chunk of the space leased by retail tenants at the complex. The list of potential replacements, however, has been dwindling.

Mall operators across the country are considering various alternatives for filling space, including leasing empty department stores to Amazon as distribution centers. Not far down the Garden State Parkway, Brookfield Properties and the Kushner family have their own ideas for transforming the Monmouth Mall. They have obtained preliminary approval to redevelop the property with a combination of apartments, shops and entertainment. But little has happened so far.

***

American Dream began its staged opening in October 2019 with its NHL-sized ice rink, Nickelodeon theme park and It’Sugar, a three-story candy store. There were no other shops. No restaurants. More of the complex was set to open in the spring of 2020, but the pandemic forced Triple Five and other mall operators to shut down.

The complex reopened with little fanfare on October 1, 2020, with only seven of the 20 planned attractions, including a food court, and a scattering of stores such as Primark and Zara. Promised amenities—full-service restaurants, a kosher food court, movie theaters—were still missing. As of November, Legoland was expected to open “soon.” The luxury wing of American Dream, consisting of about 75 stores, is scheduled to open sometime in 2021. On our tour, Ghermezian showed off the koi ponds (sans fish and water) and sleek storefronts of brands to come: Hermes, Tiffany’s, Saint Laurent, Saks Fifth Avenue, Dolce & Gabbana.

Cardi B, the Grammy-winning rapper who has 78.2 million followers on Instagram, gave the place a shout-out in early November—“Me and my lil cranky baby at @americandream”—after spending time at Nickelodeon Universe Theme Park, which operates next to the water park.

The attractions are not cheap. A day at the water park, for instance, can cost $89 per person, age 10 and up; it’s $79 for ages three to nine.

Although it has finally begun to generate some excitement, there’s no hiding American Dream’s signs of stress. The pandemic shutdowns and the subsequent restrictions to 25 percent of capacity have crippled the ability of mall operators, including Triple Five, to make their loan payments. Indeed, Triple Five missed at least three $7 million payments on Mall of America’s $1.4 billion mortgage, a default that further darkened the cloud over American Dream. Meanwhile, a number of American Dream construction contractors have sued to get paid.

“They were expecting cash flow to come in much quicker before the pandemic hit,” says Vince Tabone, senior retail analyst at Green Street Advisors. “Tourism is going to be a big factor in whether this property is successful or not.”

After investing $548 million of its own money and obtaining $1.7 billion in construction loans, Triple Five raised another $1.1 billion in 2017 for American Dream in the largest sale of unrated, high-yield municipal bonds—what used to be known as junk bonds. The lenders required that the company pledge a 49 percent stake in both Mall of America and the West Edmonton Mall in a process called cross-collateralization. The associated-risks section of the bond offering ran 38 pages.

Shortly before Thanksgiving, Gheremezian said that Triple Five was negotiating with its lenders over a forbearance agreement, in which the lenders would defer current loan payments.

Lisa Washburn, managing partner of Municipal Market Analytics, says the price of Triple Five’s bonds has “dropped pretty dramatically” because of its exposure to an industry hard hit by the pandemic. “This is all hitting at a time when American Dream is at its most vulnerable position,” she said.

Jeffrey Lahullier, mayor of East Rutherford, says he remains willing to work with Triple Five to make American Dream successful. The company is current on direct payments pledged to East Rutherford ($750,000 in 2020), but the borough is owed another $315,000 in American Dream payments that are supposed to be funneled through the NJSEA.

“I truly believe that this could be a great economic engine for both East Rutherford and the Meadowlands,” Lahullier says. “Sales tax revenue, hotel tax, and much-needed job opportunities for our residents are the plus sides, with added traffic and crime being the downside.”

Vincent Prieto, president of the NJSEA, did not return calls requesting comment.

The financing for American Dream was based on Triple Five’s expectation that the complex would draw 40 million visitors a year, or 109,589 people a day. That’s 25,000 more people than the number of attendees at a sold-out Jets or Giants football game at the adjacent MetLife Stadium.

Triple Five projected that half its visitors would be New York City tourists, a bumper crop of 67.4 million in 2019. That may have been a tall order in normal times, given that only one in five New York tourists make their way from Midtown to Lower Manhattan, let alone across the Hudson River. But during the pandemic, it’s all but impossible.

Shortly before Thanksgiving, NYC & Company, the city tourism and convention agency, estimated that in 2020, only 22.9 million visitors—one-third of 2019’s number—would make their way to New York. And the agency predicted that it’ll be a long road back, saying the number of visitors may not hit 69 million until 2024.

“The problem is, we don’t have any international tourists,” says Nick A. Egelanian, president of SiteWorks and a shopping-center expert. “You’re not getting major tourism back to New York for a long time.”

Egelanian gave Triple Five a 60 percent chance for long-term success. “The concept is too ambitious, and the damage from an extended period of reduced viability could become too much for the project to bear,” he says, adding that they will likely retain management and ownership of the property overall. “It was a risky project made riskier by the pandemic.”

Ghermezian dismisses such talk. He claims to have commitments for 84 percent of the total space at American Dream. At deadline, he estimated that more than 100 of what he hopes will be 325 retail shops and restaurants (once estimated at 500) were open, with another 100 under construction.

Each week, Ghermezian says, word of mouth about American Dream spreads. The ski hill and other attractions, he says, are selling out on the weekends, while keeping capacity in compliance with state and federal health and safety guidelines.

“We’re working through all the issues now,” he says. “Yes, we have issues. All the lenders understand that if anyone is capable of managing through a pandemic, it’s Triple Five. By the end of [2021], we should be close to 100 percent occupancy.”

But if Governor Phil Murphy is forced to lock down the state again, “it would be absolutely devastating,” he concedes.

And so, 17 years after it began, question marks still hover over American Dream.