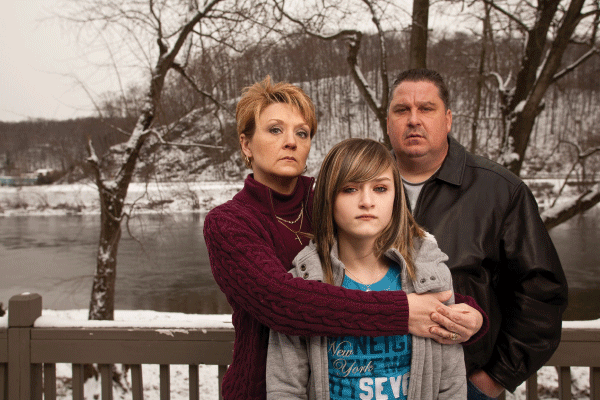

Heavy rains have a way of upsetting Meryl McGinley’s daughter.

As the precipitation slashes down, the 12-year-old, who experienced three floods during the course of eighteen months, relives the trauma of the family’s home filling with water, torrents rushing to the second floor.

“If the river rises even a foot, our daughter calls me at work in a panic,” McGinley says. The McGinley family lives on the Delaware River in Carpentersville, just south of I-78.

Like other residents on both sides of the Delaware, mainly from the Water Gap south to the Lambertville/New Hope area, the McGinleys are enraged about the floods that have threatened their lives and their homes three times in recent years.

Flood victims—and their insurers—say they know who is to blame for their troubles. They point across the state to New York City, which draws drinking water from three upstream reservoirs. The victims say New York City is obliged to leave extra capacity—or voids—in the reservoirs to take on more water during heavy rains. Big Apple officials claim the reservoirs need to be kept close to capacity at all times to satisfy New Yorkers’ needs.

Life on the river was calm for several decades until the floods of 2004, 2005, and 2006. According to published reports, the floods cost nine lives and $500 million in property damage in four states. Flood victims say the New York City reservoirs were all near capacity at the time of those devastating floods.

Bill Watras had just purchased his dream house near Harmony and had finished refurbishing it when the first flood hit. “Hurricane Ivan came and he brought lots of water quickly,” Watras recalls. “We had everything just moved in, and water reached light switches on the second floor.” Watras lost everything, but rebuilt—and was flooded out again six months later—this time water rose to the roof. He rebuilt yet again and was flooded out a third time one year later. He never did move into that dream house and has moved to Oxford.

Although the flooding crisis is new, the controversy dates to a 1931 Supreme Court ruling that the interests of each of the four river-basin states—Delaware, New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania—should be given equal consideration in the management of the shared waterway. The concept was reinforced by a 1954 Supreme Court decree signed by the four states and New York City officials. These rulings helped to establish some of the principles behind the river’s Flexible Flow Management Program, a temporary plan established in 2007. But to flood victims, the FFMP is a flawed plan that has been abused by New York, which is miscalculating its water needs, even hoarding water, the flood victims say.

Management of the river is overseen by the Delaware River Basin Commission, a regulatory agency comprised of the governors of the four river-basin states and one federal government commissioner. To date, only Pennsylvania Governor Ed Rendell has publicly connected New York’s reservoirs with the flooding downstream.

Although Governor Jon Corzine has been mum on the issue, New Jersey flood victims see hope in a report issued last fall by the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection. The Safe Yields Report concludes that New York City could live with reduced levels in the Cannonsville, Neversink, and Pepacton reservoirs. Experts say that would significantly reduce the chance of flooding.

Corzine’s office would not comment on the report, instead referring New Jersey Monthly to the DEP. Elaine Makatura, a DEP spokesperson, acknowledges that the report “indicates there are alternative ways to manage the operation of the reservoirs that can better meet the needs of stakeholders without shortchanging New York City’s water supply.”

So why isn’t the commission taking action based on the report? According to Lee Hartman, vice president of Friends of Upper Delaware River, “The decree parties didn’t look at it seriously and decided to remain status quo on FFMP.”

Hartman also serves as Delaware River Committee chairman for the Pennsylvania Council of Trout Unlimited, a fisheries organization. Fishermen are interested parties, since the FFMP affects the river’s flow and temperature and therefore the health of its fish population.

Fisheries groups have banded together with flood victims’ advocacy groups like the Delaware River Conservancy to pressure the Commission for change.

“With winter storms and spring rains coming, and the three reservoirs full, we cannot wait for the Basin Commission to do nothing,” says Gail Pedrick, Pennsylvania director of the Conservancy. “We need immediate plans to provide us with a flood-management plan, not the dangerous one they have now. We want permanent year-round safety voids of 20 percent.” She points out that it can take several weeks to lower reservoir levels to create sufficient voids in anticipation of heavy rainfall.

A New Hope resident, Pedrick painstakingly rebuilt after three floods. To spread the word that the Conservancy wants voids in the three reservoirs, Pedrick has handed out flyers, gathered petitions, written press releases, placed newspaper ads, and met with elected officials, including Rendell. Although no floods occurred in 2007 and 2008, Pedrick and others who live near the river fear the worst is yet to come.

By banding together, the flood and fishery groups hope to achieve more consistent releases of water from the three reservoirs. This, they say, will allow trout to thrive and residents to breathe easier. Although the commission has withdrawn a proposal making the current management program permanent, the groups say this action is not enough.

Can anything else be done to mitigate flooding besides consistently releasing manageable amounts of water from the reservoirs to create voids? Yes, says Laura Tessieri, an engineer and certified floodplain manager at the Basin Commission, and chair of the New Jersey Association for Floodplain Management (NJAFM).

The association offers officials training in floodplain management and holds an annual conference on flooding not just for riverfront communities, but also those in the Meadowlands, the Pine Barrens, the Shore, and other flood-prone areas of the state.

Tessieri says communities, not just individuals, must get involved, and officials and emergency personnel should be trained and certified to assess risk, coordinate flood mitigation activities, and better communicate risk to the public. “Homeowners can do little to prevent floods, but they can work to be prepared for flood events,” Tessieri says.

For example, she recommends people living on the river or in the floodplain (defined by NJAFM as a flat or nearly flat stretch of land adjacent to a stream or river that experiences occasional or periodic flooding) relocate utility boxes to higher stories, know where to get accurate flood-warning information, and perhaps even elevate their homes.

But raising a residence is costly. According to Mary Alice Heimerl, a real estate agent with Coldwell Banker Hearthside in Frenchtown, homeowners can expect to spend $65,000 to $85,000 to raise their homes. “It depends on the size of the home and how elaborate they are with finishing lower levels,” Heimerl says.

Meanwhile, the floods have taken their toll on the value of riverfront properties. “The future is uncertain for these homes,” Heimerl says. “It’s impossible to predict when and if the river should flood again. Those living along the river most certainly are paying close attention to the decision of the government concerning reservoir levels upriver.”

Officials from New York City and the Basin Commission say they are delaying any decision on the reservoirs until the expected release in April of a new study conducted for the Commission by the U.S. Geological Survey, the Army Corps of Engineers, and the National Weather Service.

“We need to see the outcome of the flood model,” says Basin Commission communications manager Clarke Rupert, who notes that other studies are also underway. “The parties have many things to think about when making decisions in terms of balancing competing demands.”

Depending on whom you ask, the report may or may not back the suspicions of the flood victims. Fishery expert Al Caucci of Starlight, Pennsylvania, is pessimistic. “The bureaucrats always throw money at studies and they still maintain the status quo,” he says.

If the commission does not modify the river-management plan in the wake of the study, the Conservancy and other groups are likely to file suit. “What we cannot accept,” says Pedrick, “is a plan based on incomplete models, inaccurate data, voted in haste.”

Robert Gluck is an award-winning freelance writer. He grew up in New Jersey and lives in Pennsylvania.

To read more stories from our Waterfront Getaways issue, click on the links below: