Larry Niles, former chief of the ENSP who currently works on various wildlife projects all over the world and throughout New Jersey, says there are no easy fixes. “It’s worse than anyone can imagine,” says Niles. “What I tell people is you’re wrong if you think biologists [alone] can help you out of this.”

The consequences of extinctions can be dramatic, even hitting the state economically. The annual migrations of shorebirds alone bring in tens of millions of dollars in tourism money to the state, says Mooij.

The threat to bats can also have a financial impact. They are one of the best and cheapest forms of pest control. One little brown bat can eat up to 3,000 insects in a single night, including gypsy moths, stink bugs and mosquitoes. Studies have also shown that bats, who act as pollinators, are worth billions of dollars to the agricultural industry worldwide—an industry that happens to be the third largest in the state.

The bats’ consumption of mosquitoes potentially depresses the number of mosquito-born illnesses like West Nile virus. With the current focus on Zika virus, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently released maps showing that the two types of mosquitoes that might carry the disease could be present in New Jersey. Feigin says she’s sure the bats here would be happy to eat them.

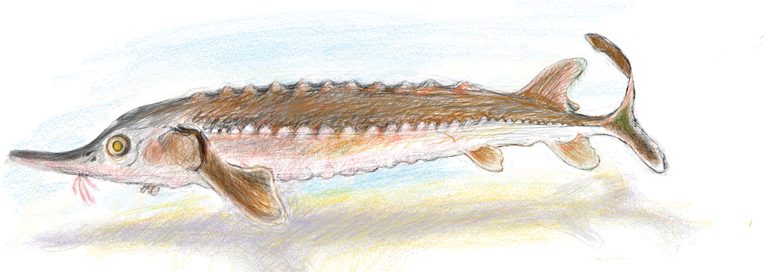

Atlantic sturgeon. Illustration by Janice Belove.

Each species—whether predator or prey—has its place in the circle of life resulting in biodiversity and balance in the state. “A functioning ecosystem includes all of the parts, and these species are the parts,” Jenkins says.

To protect biodiversity while development continues, Jenkins says his agency is focusing on habitat management and restoration. This is especially important in New Jersey because, while specific landscapes in the state are protected, the habitat of listed species is not directly protected under the state’s ENSCA.

“There’s no law that protects an endangered species’ habitat,” Niles says. “If it doesn’t fall in a wetlands, if it doesn’t fall in the Pinelands, then there’s no law against destroying [the] habitat.”

One of the ENSP’s main projects is to identify areas inhabited by the state’s most imperiled creatures. The Landscape Project, started under Niles in 1994, maps the occurrences and the habitat of these species.

The project pulls information from a geographic-information system database called Biotics, compiled by CWF biologists. The information is a mix of data from ENSP surveys, professional surveys and rare-species sighting reports submitted by the public via the ENSP website.

“We encourage people in the general public to submit their observations, because our biologists just can’t be in every corner of the state every day,” says the CWF’s Mike Davenport, who has worked on Biotics for over a decade. “It’s also helpful in private lands that we might not have access to.”

The Biotics data, along with land-use information, is used to create Landscape Project maps. The interactive maps, while not law, can be used “for planning purposes before any actions, such as proposed development, resource extraction or conservation measures, occur,” according to the New Jersey Division of Fish and Wildlife website. Landscape Project findings are also used to identify land to protect (and sometimes acquire) through state funding initiatives like Green Acres, which sets aside money for recreation and conservation needs.

Zoologist Brian Zarate works on connecting habitats for imperiled species with tunnel and fencing projects like this one in Bedminster. Photo courtesy of Jonathan Carlucci.

Another ENSP initiative, the Connecting Habitat Across New Jersey (CHANJ) project, aims to preserve and restore valuable habitat corridors through which terrestrial wildlife need to move in order to breed, as well as find food, shelter, water and other resources. Often, these corridors are blocked or interrupted by development or well-traveled vehicular roads.

“CHANJ is to identify those areas that we think are the most important to maintain or restore the ability of wildlife to move through the landscape,” Jenkins says. “We will in some cases have to secure the habitat and buy it, or get landowner easements or agreements. Then it’s restoring… [and] managing the habitat so that it becomes more conducive to wildlife moving through it.”

One way the land can be managed is through the installation of wildlife road-crossing structures like tunnels and bridges. A first-of-its-kind tunnel system was installed last summer beneath River Road in Bedminster. The $90,000 initiative—a partnership between the state DEP, the township of Bedminster and New Jersey Audubon—included the installation of wooden fencing spanning 2,000 feet on either side of River Road, which steers wildlife to one of five tunnels. Built with threatened wood turtles in mind, the tunnels can accommodate small reptiles, amphibians and mammals as large as a fox.

Gretchen Fowles, an ENSP biologist and coleader of CHANJ, says alliances make such initiatives possible. “We’ve had partnerships with conservation organizations, the transportation agencies, municipalities—whoever has jurisdiction over that roadway—wildlife experts, they all come together to come up with a solution,” says Fowles.

New Jersey has about a dozen structures used by wildlife. ENSP zoologist Brian Zarate, a CHANJ coleader, says animals sometimes utilize crossing structures like bridges and footpaths meant for hikers and bikers. Structures designed specifically with wildlife in mind include three Route 78 overpasses built in Somerset and Union counties in the 1970s—the first such project of its kind in the country, says Zarate.

Two more tunnel projects are planned, including one for Waterloo Road in Byram Township, a valuable tract of land for amphibians like the Jefferson salamander, a species of special concern. Highly susceptible to road mortality, amphibians, who cross in the thousands during their March migrations, currently have to be helped across the road by biologists and volunteers.

“We’ve been working really hard to find funding to get permanent tunnels put under the road,” says Fowles, “so people don’t need to be out there helping to shuttle these animals across.”