Okay, a good news day doesn’t mean all good news, but an hour before the meeting to set the evening broadcast lineup, the intensity builds in the newsroom on the third floor of 30 Rock. Office phones, cell phones, and BlackBerries ring in an information-age chorus, arming reporters and producers for the battle to support their stories. Earnest intelligence, passive-aggressive cajoling, and gallows humor abound as the journalists passionately plead for air time.

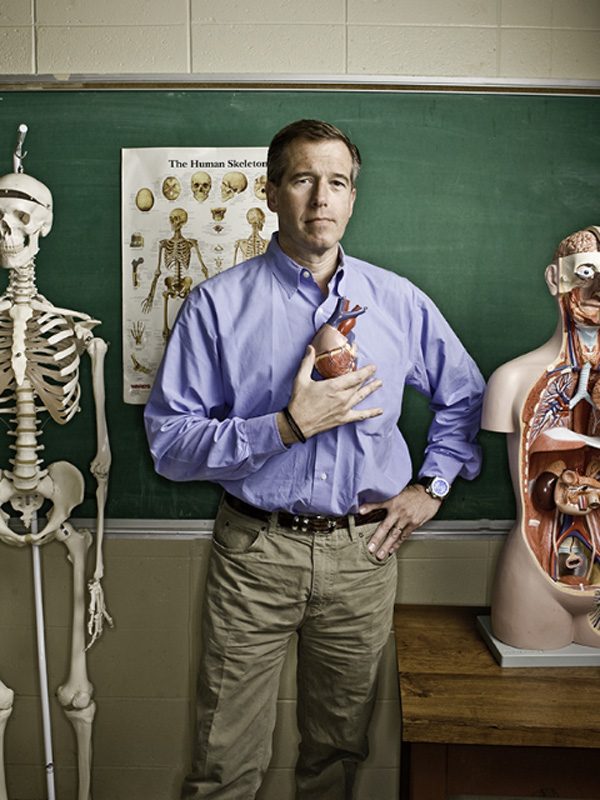

In the middle of the mayhem, NBC Nightly News anchor Brian Williams, 49, talks with staffers about the future of the young YFZ mothers and children who are allegedly at risk in the Texas cult. All crisp creases and irreverent gravitas, Williams adjourns to his corner office ten yards from the scrum.

His office reflects his passions. An autographed football, a microphone cover from his old gig at WCBS-TV in New York, family photos, NASCAR merchandise, and letters signed by past U.S. presidents are arranged on the walls and shelves. But most prominent among the mementos is the helmet he wore as a volunteer with the Old Village Fire Company in Middletown.

“I am just a fire dog at heart,” he says. “It started when we lived in Elmira, New York, right before we moved to Middletown. I was 8 when my dad heard the sirens and threw us [Williams and his three older siblings] into the car. We witnessed what has come to be known in those circles as the Cash Electric fire. I was mesmerized by these brave men fighting to save the store on the main street of town.”

Eight years later, as a senior at Mater Dei High School in New Monmouth (class of ’77), Williams volunteered. “I spent a year as a ‘probie.’ That’s probationary firefighter to you civilians,” he says with a smile. “And it became just a huge part of my life. Do you watch Rescue Me, Denis Leary’s show? Fabulous. It completely captures the hilarious and profound bond among the members of any company.”

Williams is incapable of talking about New Jersey without mentioning his time in the firehouse, and he loves to talk about both. You believe him. Not because he is behind a desk with that perfect anchor’s voice, but because he surrounds himself with reminders of who he is, like the simple piece of knotted leather on his wrist, a talisman of the surf that he loves.

There’s an underlying humor to everything Williams says, a skewed view born of his Irish-Catholic upbringing, firehouse chats, a life chasing news stories, and his Jersey youth.

“The folks here know not to tangle with me on the Garden State,” Williams says, “and for the uninitiated, if you intend to start something, you’d better bring a couple of friends.”

“My dad, Gordon Williams, worked for Corning Glass in upstate New York, and when the company lopped off payroll, he found a job in Middletown,” Williams says. “We moved there when I was 10. There was a strip of woods with a stream that provided an endless source of adventure. On one side was Value City Furniture on Route 35, and King’s Highway was 100 yards away on the other side. It was such a happy life. I was a late-in-life baby for my parents. My siblings are sixteen, fourteen, and eight years older, so I was kind of an only child, but it was a completely happy life. I had friends, lots to do, I learned to body surf. I just loved it.

“My mom, Dorothy, was a character. She loved Max’s hot dogs in Long Branch. Some would prefer the Windmill, but she had the car keys, so I became a Max’s guy. From the top of my street I could see the Verrazano and then I got to watch the Twin Towers rise into the sky. It always felt like a beacon to the city.”

Williams lost many friends in the attacks of September 11, 2001, and is moved discussing how Middletown’s suburban calm was destroyed by the deaths of 37 residents. “One minute everything is perfect on this glorious late-summer morning, and the next it’s all shattered. I look at a satellite map and no longer see the towers … It’s something that I can’t shake,” he says. “The towers were New York to me. And to see the firefighters who went in there and gave up their lives to save others, it makes me feel silly to talk about my own time in the house as a fireman.”

In the lineup meeting, Williams listens, asks pointed but encouraging questions of journalists and producers pitching their pieces, and goes with the flow of the session.

He says his collaborative nature is the result of his experiences. “At the end of the day, I am just a college dropout who got lucky,” he says. The dropout part is true. From high school to Brookdale County College, then to George Washington University, and finally to Catholic University, he was an indifferent student. But the luck part is fiction. Williams earned his way.

“There wasn’t a lot of money at home, so I had to pay my own tuition to Mater Dei,” Williams says. “I was a busboy at the Perkins Pancake House on Route 35; I worked at Sears, which was right near our house. I even sold Christmas trees out of the back of a truck in Red Bank. That wasn’t a bad job, until a guy came up and stuck a .38-caliber pistol in my face and made me hand over all the money. Merry Christmas, right? Of course, I suddenly appreciated the other jobs I thought I hated.”

That’s the Jersey in Williams. Work your ass off to get where you want to be, then pass it off as good fortune. “As a kid, I was always mesmerized looking into other people’s houses and seeing the blue [TV] glow that held their gaze,” he says. “I always thought it would be interesting to do but never thought I would make it.” But he did, which forces him into a half-apology for his success.

“I don’t feel any different than I did when I was back home,” he says. “Sitting around the firehouse with some of my old pals now, I am as surprised to be where I am as they are surprised to see me in their living rooms.”

But Williams was also reading the New York Times front to back. “My dad mandated that we read the paper each day,” he says. “I figured that was a good one to pick. I was facing a decision—take the Middletown police exam or go back to Catholic University.”

One friend never doubted where Williams was headed. “I’ve known him since he was 18,” says Bruce George, “and he was the most focused young man I’ve ever met.” George, a former chief and Williams’s Captain at the Old Village firehouse, adds, “When Governor Cahill decided that 18-year-olds were adults, it meant they could be firefighters. Brian volunteered the minute he could, and he loved every minute of it. In a company, it’s important for the men to bond. Brian fit in right from the days of being a probie. He was a great listener, he was like a sponge.”

What happens in the house, stays in the house but George does give up a few details. “I am not sure if you’ve noticed this,” George says, “but Brian’s sort of meticulous. He likes everything to be just so. He always wore a white shirt, jacket, and tie. He had a rack in the back of his car where he hung his perfectly ironed clothes. The guys liked to tease him about it. When they’d come back from a fire, they’d sneak into his car and stick their dirty hands inside his jacket just to mess with him. But he gave just as good as he got.”

“I wouldn’t trade any of the times I had with the guys,” Williams says. “We would go to Middletown Bowling Lanes to hang out. It had everything a guy needs—bowling, pinball, fried food, and a bartender who just happened to be with the Old Village crew. We’d pay almost nothing for food and drink, and then somebody would swear they heard a guy who knew a guy say Bruce Springsteen was showing up at the Stone Pony or the Tradewinds, and we’d be off, hoping in vain that he’d show up.”

Williams is a Springsteen junkie. “Stalker is probably more accurate,” he says. “One of the great perks about this job is I get to meet some of my heroes. I am happy to say that I’ve gotten to become friends with Bruce and Patti.”

Like the Boss, Williams is a car freak. So when Bruce belts out, “I got a ’69 Chevy with a 396/ Fuelie heads and a Hurst on the floor” in “Racing in the Street,” Williams can lean over to the dentist from Mahwah sitting next to him at Giants Stadium and translate; this avowed gearhead is a NASCAR nut who knows his way around an engine block. “My dad took us out to the track near Elmira, and I got hooked. And I am in mourning since I found out that the track in Wall Township has closed for good.”

George confirms Williams’s grease-monkey bent. “All the guys in the [firehouse] were regular guys,” George says. “He always pulled his weight. But he was also a notch above. We knew that he had his eye on bigger things. ”

Another guy who made it big without losing his Jersey mojo echoes George’s comments. “Brian is very unpretentious,” says Springsteen. “The formality you see at the anchor desk on NBC News is a seriously talented man going about his work. Once the jacket and tie come off, he’s a huge music fan—funny, profane, irreverent—and the Jersey fireman inside him quickly rises to the surface. He’s easy and fun to be around.”

As gregarious and fun loving as he is, Williams is not without heartache. He lost his sister, Mary Jane Esser, and his brother David, as well as his mother. His brother Richard lives in El Paso, Texas. He recounts his early career and family information easily but clearly keeps real pain to himself.

Williams’s work ethic contributed to luring him from school. “I got an internship with the Carter administration, which turned into a year working for the National Association of Broadcasters, and I was young,” he says. “I went from having no money to having a little money, and I didn’t think I needed to go back [to college]. It worked out okay, but it’s my biggest regret.”

With no on-air experience to speak of, Williams landed his first TV job in Pittsburg, Kansas. A year later, he returned to D.C. and found work covering North Virginia at TV station WTTG and filling in on public affairs show Panorama, where he met the show’s executive producer, Jane Stoddard. Although she was from Connecticut, her redeeming qualities included an unceasing fealty to Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band. That sealed the deal. They have been married 22 years.

A year after marrying Jane, Williams landed a job covering South Jersey for WCAU, then a CBS affiliate in Philadelphia. “It was heaven,” he says. “I was covering the rebirth of Atlantic City, I was in the Pine Barrens, I was back in Jersey.” In 1987 he moved to WCBS in New York, and the seismic shift happened. He and Jane moved to Connecticut.

“I was doing the 11 pm broadcasts in New York, we had two small kids (Allison and Douglas, now 20 and 17, respectively) and Jane’s parents were a mile down the road,” he says apologetically. “But I am still close enough to get back to Jersey in about an hour.” In 1993, Williams was hired away by NBC and worked his way from anchor of the national Weekend Nightly News to chief White House correspondent to host of an hour-long MSNBC show before taking over for Tom Brokaw in 2004.

“I don’t think it’s any coincidence that I am in this business,” Williams says. “There’s a rush, a sense of mission. It’s the same charge whether it’s heading out to a fire, getting behind the wheel of a race car, or getting a breaking story. It’s the thrill of doing something unusual. When I was away at school I would come home and spend weekends and vacations in that firehouse. I slept with my boots next to my bed. I wore those same boots, which I bought in 1976, when I covered the aftermath of Katrina in New Orleans.” Williams was awarded one of his seven Emmy awards for his Katrina coverage.

On May 7, Williams’s NASCAR pals had nothing on him. He was embarking on a mad 40-minute sprint to Red Bank.

“Patti called me an hour before the broadcast that night and asked if Jane and I were making the show.” That was Patti Scialfa asking Williams to introduce her husband’s band at a fundraiser for the Count Basie Theater.

“Now, I want it on the record that I do not advocate the flaunting of Garden State traffic laws,” Williams says, “but I can promise you that I was cruising down the Jersey Turnpike.” In layman’s terms, he was haulin’ ass.

“We hit the dips at the Turnpike near Newark airport at high speed. I was pulling zero Gs and I knew we’d make it,” he says. “When we got there, it was like a Scorsese movie. We parked by the back door, they loosened the ropes for us, and we were in. We chatted with Nils Lofgren and the Mighty, Mighty Max Weinberg, and the next thing I know, I’m out on that stage.

“So I pulled the microphone out of Bruce’s stand and addressed the crowd. I really didn’t have time to think straight, let alone prepare for this moment. My mom had performed on that stage when I was a kid and now I’m here announcing the E Street Band? You’ve got to be kidding me.

“Some guys yelled out the name of my high school Mater Dei and I got heckled by some Red Bank Catholic alums we tussled with as kids. I talked about the recent loss of Danny Federici, and said, ‘As you know, we’ve had a loss in the family. Great families endure. And great bands endure. The netting attached to the ceiling is just to keep the larger pieces of debris from falling down. And if there’s any band in the land that could cause the big ones to fall, and bring the house down, it’s this group. Ladies and gentlemen…’ And that’s when I got drowned out.” The band played the Darkness on the Edge of Town and Born to Run albums, in order, in their entirety. And a legendary night was created.

“Jane and I were in the second row,” Williams says. “Half an hour flew by before I realized I was sitting behind Governor Corzine. The rest of the night was spent enraptured, connecting with friends and strangers alike.”

Springsteen says he’s gotten used to America’s anchor being in the crowd. Sort of.

“It’s a bit disorienting to see him right there, I would say,” Springsteen acknowledges. “Particularly because when Brian is in the pit of an E Street Band show, he usually has his shirt off and is dancing wildly with his wife, Jane. Well, maybe just his tie is off…”

“I love that Bruce said that,” Williams says when told of Springsteen’s description of him. “My language is rougher than most, but it’s who I am.”

For Williams, it’s part of the job to keep a piece of himself hidden, projecting an unflappable air no matter how dire the stories he has to share with millions of viewers. On the other hand, he gets to reveal himself to captains of industry, world leaders, and his sports and entertainment favorites.

“One of my most enjoyable moments was being around the set of The Sopranos. I am the kind of idiot who notices a soda can in the wrong place from one frame to the next. I somehow wound up at a taping. Just being around those people was a joy, and, all due respect to the issues of stereotypes, it was a terrific portrait of New Jersey and a certain segment of the population that may or may not exist. Now, I have no whitewashed notions about the Garden State,” Williams notes. “I was taking the Acela [express train] to Washington recently, and just as we’re slowing down near the”—here he looks over the top of his frameless glasses with a wry smile and a faux-reverential tone—“Frank Lautenberg Transfer Station in Secaucus, I see down below in the Meadowlands two guys definitely up to no good. They’re about to take someone or something out of the trunk. And I just thought to myself, Man, I love the Garden State.”

Williams is in the state a lot these days. “My dad is 91 and he’s in an assisted living facility in Red Bank,” he says. “I get down to see him pretty often and every time I get on Route 35, I just feel like the air is right, the people, the places are right, and I am in my power corridor. And when I get together with some of my old friends at Applebee’s after I visit my dad, I just feel completely at home. It’s my magnetic north.”

David Chmiel lives in South Orange and is a frequent contributor to New Jersey Monthly.