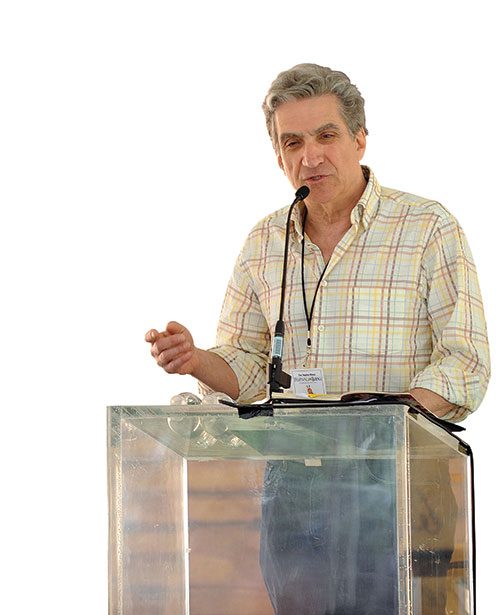

Robert Pinsky is many things—a 1962 Rutgers grad, a three-term United States Poet Laureate (1997-2000), a Pulitzer Prize nominee (for The Figured Wheel: New and Collected Poems, 1966-1996), an award-winning translator, essayist, and critic, and a renowned professor, currently teaching at Boston University. But if you ask Pinsky, 69, about himself, the first thing that comes up is Long Branch—his hometown and a deep influence on his remarkable career. In fact, Pinsky’s latest essay collection, Thousands of Broadways, takes its name from Long Branch’s main thoroughfare and uses local history and photographs as a jumping-off point for meditations on the ways small-town America has been depicted in literature and film.

How did Long Branch influence you as a writer?

As an historic resort—visited by seven American presidents, Winslow Homer, Diamond Jim Brady and Lily Langtree, all of that—with the racetrack and the beach, and the off-season quiet to add some elegiac melancholy, the town was inherently poetic. And the Jewish and Italian people of my parents’ generation used the English language with pizzazz. I grew up among expert joke-tellers, arguers, and complainers.

What were your family’s Long Branch roots?

In the 1920s, my grandfather Dave Pinsky had a not-legal liquor enterprise with his partner—later competitor—Izzy Schneider. My other grandfather, Morris Eisenberg, washed the windows on stores downtown and was also a part-time tailor. My aunts and uncles and cousins and parents all attended Long Branch High School, as did my brother and I. What kept us in town? I guess inertia! Or the temperate ocean climate. My dear Aunt Dot still lives on Delaware Avenue, same house as when I was in primary school.

The subtitle of your new book is “Dreams and Nightmares of the American Small Town.” What’s the nightmare part?

The line between the comforting quality of a small town and the stifling quality of a small town is one I think anybody who’s lived in a town has experienced. [Knowing everyone] can be very comforting. On the other hand, everybody knowing a lot about who you are can sometimes feel not that great. I don’t think there’s anything strange or bizarre about the two extremes of the way a town gets into your imagination.

What does New Jersey stand for in the cultural imagination?

It may be the most American state. It has the most different things in it, urban and rural, and the most ethnicities, so you have a rich cultural mix. New Jersey still does more truck farming than any other state. It has natural beauty and unnatural ugliness. In Long Branch you had horse racing and the ocean, and it’s close enough to Manhattan that you can be inspired by the city and go to it and long for it. Its relation to Manhattan is yearning—not mere possession—so it may be an optimal place for imagination.

What is the state of poetry in the nation today?

There are a lot of poetry organizations, a lot of poets, a lot going on. It may have to do with a kind of reaction—we love mass media, we love digital stuff, but then there’s also an appetite for something opposite, on a human scale. And poetry, as I’ve said many times, is by its nature, on the scale of one person’s voice. The videos at favoritepoem.org demonstrate what I mean.

What do you make of Long Branch today?

To see the old boardwalk gone and these not particularly interesting new condos there instead, to see the downtown trying to struggle back but not be what it was, I shed a tear for my father. He died about five years ago. He probably would not have grieved as much as I do on his behalf. But I tell myself that somebody who saw Long Branch in the 1930s, when my father was in high school, might have wept because it wasn’t the town they knew in the nineteenth century. I still have a kind of grief that Long Branch isn’t what it was.

In the last chapter of your book you warn against nostalgia. What is the difference between nostalgia and elegy, which you seem to argue for?

Elegy pays attention to the reality of loss and change. Nostalgia tends to want to skim off the sweetness.