The 41-foot-tall, 10,710-pound behemoth looms large against a cloudless sky over Sandy Hook. It is one of two Nike missiles on display at Fort Hancock, awesome reminders of a not-so-distant era when the metropolitan area was a bastion of defense against a feared nuclear showdown with the Soviet Union.

Today, the missiles are among the tourist attractions at Gateway National Recreation Area, also home to Sandy Hook’s beaches and lighthouse. This fall, the National Park Service will offer tours of the missile site two to three days each month. Guides will take visitors close to the missiles (yes, you can touch them), into the control vans to see the launch and guidance equipment (an array of screens, buttons, switches, and 1960s-era computers), into the nearby launch pads, and for a look down an entryway to underground missile storage magazines .

Fort Hancock is the most complete of the fifteen former Nike sites in New Jersey—although traces remain of the others throughout the state (see story, page 88). Many regard it as the country’s second-best Nike site—after San Francisco’s Golden Gate National Recreation Area.

As far back as World War II, the Army explored the idea of a surface-to-air missile (SAM) guided by ground-based radar and computers. An Army colonel who loved classical literature suggested the project’s name: Nike, after the Greek goddess of victory.

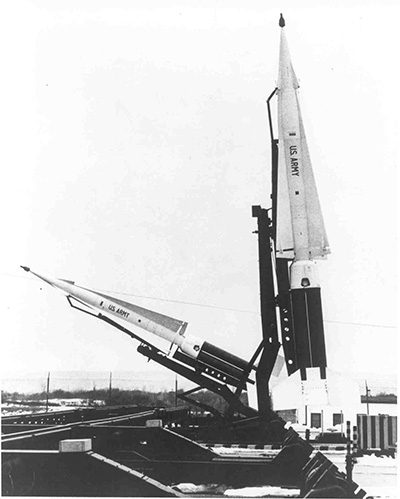

In 1954, the Army unveiled the Nike Ajax (named after the mythological Trojan War hero), a liquid fuel missile with a range of up to 30 miles and speed of Mach 2.3 (twice the speed of sound). The Ajax was soon followed by a second-generation SAM, the nuclear-tipped Hercules (for the Roman legend), propelled by solid fuel to Mach 3.65, and capable of taking out a whole squadron 75 miles away.

Sandy Hook had guarded the entrance to New York Harbor since colonial times, so it was only natural Fort Hancock received the Ajax, and later became one of the first to upgrade to the Hercules. The Army began cutting back its presence at Sandy Hook in the 1960s and finally closed down the base in 1974—due in part to the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks. The National Park Service became the guardian of all of Sandy Hook in 1975. The park superintendant wanted to preserve the missiles and equipment, but the Army sold it all as scrap, and the Command and Control Center behind the twin lighthouses in Highlands was obliterated.

The site remained barren (except for the four underground missile magazines) until 2001, when the park service rescued five about-to-be demolished control vans and five radar antennas from Pennyslvania’s Letterkenny Army Depot, and secured an Ajax on its launcher from a private collector. Tours began the following year. Two more Ajax and the Hercules with its launcher were obtained from Florida’s Patrick Air Force Base in 2006.

Today, Fort Hancock tour guides take visitors over the man-made hill covering the magazines, originally housing 40 Ajax, later replaced by 24 Hercules missiles. Tour guide Pete DeMarco, who served in the army at another Nike base and at the New England-area command center, gets a kick out of imparting information to local residents. “When we tell them there were nuclear weapons here, the looks on their faces! They never knew it,” he says.

No missiles were ever fired at Sandy Hook, but there were several alerts: stray passenger jets, the 1962 Cuban missile crisis, the 1965 Northeast blackout, and the Israeli wars in 1967 and ’73. The summer of 1970 brought the big one. “We got within five minutes of a launch, and held for 45 minutes to an hour,” says tour guide Bill Jackson, who long ago served in the army at Fort Hancock. A Soviet bomber had intruded into U.S. airspace, and the crew waited while Air Force fighters chased it away. At moments like that, Jackson says, “it was driven home to us just how important what we were doing was.”

New Jersey did see its share of accidents, though. In 1958, at the Nike base in Middletown/Leonardo, an Ajax inadvertently detonated; a memorial to the ten killed stands at Fort Hancock. A lesser rival to the Hercules, the Air Force’s BOMARC, caught fire in 1960 at Lakehurst Naval Air Station in Ocean County, releasing plutonium into the air (remediation continues today).

Tours are free with admission to Sandy Hook and will be held October 9 and 24; and November 6 from noon to 4 pm. Three days of special Fort Hancock events will be held October 22–24. For information, contact 732-872-5900 or visit nps.gov/gate.

***************************

Seeking Vague Traces of New Jersey’s Nuclear Past

Although New Jersey was the Cold War-era home to fifteen Nike missile bases or command centers, few residents realized these weapons of mass destruction—including in most cases nuclear-tipped Nike Hercules missiles—were parked practically in their backyards. Even today, we routinely pass the old Nike sites without recognizing the clues to their not-so-long-ago roles in the U.S. military’s strategy for the defense of the New York and Philadelphia areas.

Don Bender, an advertising and marketing consultant and recognized expert on New Jersey’s Cold War history, says his parents were clueless about the Nike battery in Livingston, where he grew up. Between 1955 and 1974, the Livingston launch area was home to 60 Ajax missiles and 18 Hercules missiles. Today, the remnants of that installation—including rusted radar towers, concrete pads, and buildings now turned into artists’ studios—can be seen on a walk through Riker Hill Park off Beaufort Avenue, just east of Eisenhower Parkway. Like most other decommissioned Nike sites, there is no historic marker at the park indicating its former life.

Bender escorted me to two other Nike sites, part of the semicircle of nine northern New Jersey sites arranged around New York City. Off Route 9 in Old Bridge, the buildings are used by the Board of Education for bus maintenance. At Phillips and Veterans Parks in Holmdel, I saw nothing that hinted at the area’s previous use, but Bender showed me a clue. A manhole cover in the grass, marked with an S, indicates where underground cables would have connected with the launch area, beyond the hill in Holmdel Park.

Over the next few weeks, I scouted out more ghosts of Nike past. Driving north on Route 23, I found former launch-area buildings behind the Ski Barn in Wayne now used by Passaic County. School buses were parked above the former underground magazines where the missiles were stored. Next, I made my way up Campgaw Mountain, which straddles Franklin Lakes and Mahwah, and discovered several original administrative and barracks buildings currently housing Shadow Ridge Riding Center. In Union County, I trudged up a narrow paved road near Watchung Reservation, ending up behind Governor Livingston High School in Berkeley Heights, where I found fencing, building foundations, and pipes that were the last traces of the control area used in conjunction with the nearby launch area in Summit.

Down south, I checked out the Philadelphia defense areas. In Lumberton, the public works foreman took me down into a magazine behind the town garage. Rusting radar towers and old structures remain further along the road. A construction company uses the launch buildings in Pitman, where the control area has been taken over by Gloucester County Christian School. In Swedesboro, I spotted two radar towers rising up in the overgrown launch area off Paulsboro Road. The region’s command and control center, part of a decommissioned Army base in Oldmans Township, sits in ruin.