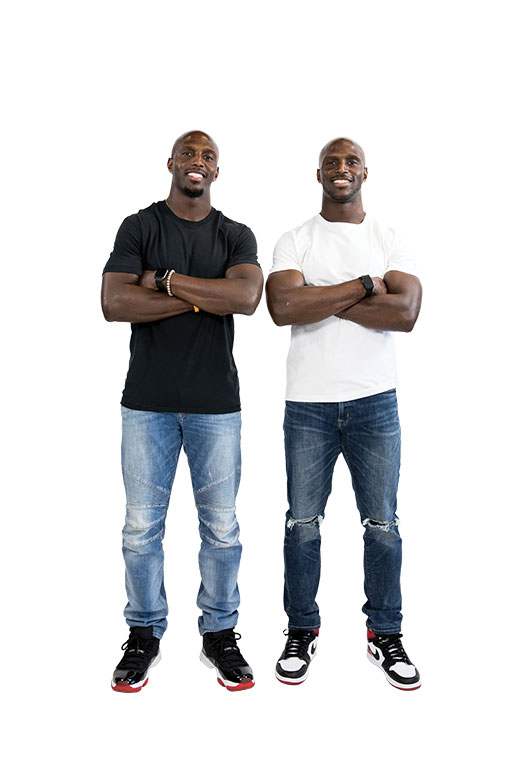

There is no distinct memory of sharing the same crib. Yet identical twins Devin and Jason McCourty, who turn 31 this month, cannot remember a single day when they did not cherish the uncanny bond that has come to define them.

There is no distinct memory of sharing the same crib. Yet identical twins Devin and Jason McCourty, who turn 31 this month, cannot remember a single day when they did not cherish the uncanny bond that has come to define them.

As kids growing up in a Nyack, New York, apartment complex, they loved trying to outdo one another in every sport they competed in. As young men, they put the rivalry aside and teamed up on New Jersey football fields during high school (at Saint Joseph Regional of Montvale) and college (Rutgers).

And for almost a decade now, both of the telegenic McCourty twins have been recognized in the National Football League as premier defensive backs—as well as for their social activism and community-service. Both have been finalists for the NFL’s Walter Payton Man of the Year award, which honors players for their excellence on and off the field.

For the last six years, the McCourtys have been passionate advocates in the search for a cure for sickle cell disease, which disproportionately affects the African-American community. They run youth camps, visit hospitals, speak out on criminal justice reform, lead blood drives, and are perhaps more attuned to each other than ever before.

They share accounts on Twitter (signing off with either “D-Mac” or “J-Mac”) and Instagram, and text and FaceTime each other daily.

“They are brothers in every sense,” says Kevin Malast, a former Rutgers teammate who lived with Jason for a year when they were members of pro football’s Tennessee Titans. “J and Dev are great people and like being in each other’s company.”

Due in part to Devin’s lobbying, the brothers are now realizing a dream. The New England Patriots acquired Jason in a trade in March, reuniting him with Devin, an All-Pro and a franchise fixture since 2010. They will be the first twins to be NFL teammates in more than 90 years.

Jason, who entered the pros one year before his brother and played for Tennessee for eight seasons and the 0-16 Cleveland Browns in 2017, will no doubt find a vastly different team experience. He has never appeared in a playoff game. Devin, on the other hand, has been part of two Super Bowl championships with the Patriots.

Still, Jason’s leadership and skills have long been comparable to his brother’s. Both have been voted team captains and are known for their athleticism, dependability and field smarts. Both weigh 195 pounds—though Jason is listed as 5-foot-11, 1 inch taller than Devin.

The similarities end there. This is Jason’s third NFL team in three seasons—and unlike Devin, he’ll have to battle for a starting job. Still, with both in the twilight of their playing careers, the twins are reunited, and it feels so good.

“It’s surreal,” says Jason. “I’m so excited about the opportunity. I guess, just to be able to now share the field with Dev, and just be able to do something that we grew up loving…. You think back to being 10 years old, waking up early to head to a Pop Warner game.”

Making the latest reconnection is another example of the twins’ positive outlook and focus on family. In a sense, it’s a tribute to their wives and small children, and to mother Phyllis Harrell, whose joy in their success knows no bounds.

Gifted athletes and close brothers, theirs is a wonderful life (both twins regularly invoke the word blessed to describe themselves). But their success would not have happened without the determination of their stern, watchful, single mother.

Devin and Jason McCourty’s life journey began in the Nyack Plaza Apartments, a low-income housing complex in Rockland County. They experienced trauma early, losing their father at age three when Calvin McCourty died of a heart attack.

A year later, Harrell, a nurse at Rockland Psychiatric Center, was severely injured in an on-the-job car accident. On disability, she struggled to provide for Devin, Jason, and their older brother, Larry, who was 17 at the time and would later enlist and serve in Desert Storm. Yet the twins “didn’t see” a sense of struggle, says Devin.

As kids, what they saw was a neighborhood that was a bit rough, always an opportunity for trouble. “I think we knew about it, but never had that inclination,” says Jason. “Coming home, that wasn’t going to be tolerated.”

Harrell made strict rules and promised herself “to build a better life for my boys.” She managed to buy a mobile home in nearby Nanuet when the twins were 11.

As one of six children, Harrell was the first in her family to go to college; she prayed she’d be able to give her twins the same opportunity. She rode them hard on their schoolwork—“no grades, no sports,” she reminded them—while demanding they “have integrity, honesty, and always try to do the right thing.”

When Jason was 11 and wanted to quit youth football, Harrell refused to buy in. Always finish what you start, she insisted. Jason still wonders where he’d be had he not heeded her directive.

Brandon Haywood, who played football with the twins in high school, never saw them do anything to embarrass the woman they called Mama Mac. “They had too much respect for her to get in trouble,” says Haywood.

Devin and Jason vowed they’d get scholarships to college to ease their mother’s financial burden. They idolized the great Emmitt Smith of the Dallas Cowboys, who used his football riches to buy his parents a new home. “We thought that was cool, and planned to do the same,” says Devin. The notion seemed far-fetched, yet by 2011 the twins had purchased a house for Harrell in Bergen County.

The road to pro football wasn’t easy. These days, scouting services identify the best athletes when they are still in middle school. At that point, the McCourtys, both all of 5-foot-6 and 115 pounds as ninth-graders, were nobody’s idea of future NFLers.

They had enrolled at St. Joseph’s Regional, an all-boys high school in Bergen County about 15 miles from their Rockland County home, rather than the sprawling public school in nearby Spring Valley. St. Joe’s was a step up academically and athletically, but the tuition—despite some financial aid— was yet another hardship. (Devin and Jason learned years later that their mother had requested her work disability payment in a lump sum to pay off debt, went years without purchasing a thing for herself, and eventually filed for bankruptcy.)

“To me, it was never any sacrifice,” says Harrell. “As a parent, it’s your job. You do what your kids need. Your kids have to be your first priority.”

At St. Joseph’s, the twins blossomed, helping the football and basketball teams to state championships. They also were honor students. “Tremendously nice kids,” is former principal Barry Donnelly’s instant assessment of the McCourtys.

Looking at colleges, it appeared they would go separate ways. Devin had injured a hip during his senior year, missing three games, and did not attract the big-time notice of his brother.

“When the Boston College coach came to our house to recruit Jason,” recalls Devin, “he didn’t even want to speak to me. That was pretty frustrating, and I never forgot that.”

Yet fate kept them together. Both landed with scholarships at Rutgers, where Devin redshirted his freshman year. In time, the twins helped bring a long-maligned Rutgers football program into national relevance, including an 11-2 season in 2006 and the school’s first bowl victory in 137 years.

Born looking and sounding alike, Devin and Jason developed a similar funny bone. The McCourtys have been known to switch seats to baffle teachers, change uniforms to confuse coaches, and pull pranks on reporters; Jason even fooled Patriots owner Robert Kraft, who thought he was congratulating Devin on the phone for being the team’s number one pick in the 2010 NFL draft.

However, the two men know they can never fool their mom, who can provide a scouting report on each twin’s most subtle differences.

Early in their NFL careers, Harrell suggested her sons become the face of sickle cell research. The blood disorder runs in their family; their aunt Winnie is afflicted by sickle cell, and their late father carried the trait. “But I told them, ‘Don’t do it unless you really get involved,’” she says. “It’s like a job.”

The McCourtys have raised more then $1 million for the disease, which affects 100,000 Americans, in large part from their annual June fund-raising run/walk in Liberty State Park.

Patriots head coach Bill Belichick likely will never have to remind Mama Mac’s pride and joy to do their jobs.

Dave Kaplan is an adjunct professor and writer/editor. He lives in Montclair.