LET’S PARTY

In 1908, the Cumberland County Historical Society erected a monument to commemorate the Greenwich Tea Party. Photo courtesy of the Cohansey Area Watershed Association.

We’ve all heard of the Boston Tea Party, but in the years before the American Revolution, a group of New Jersey patriots threw a little soiree of their own. On the night of December 12, 1774, about 40 colonists in the Southern Jersey township of Greenwich stole and burned a shipment of British tea that was bound for Philadelphia. The British were not pleased.

SAVED, FOR NOW

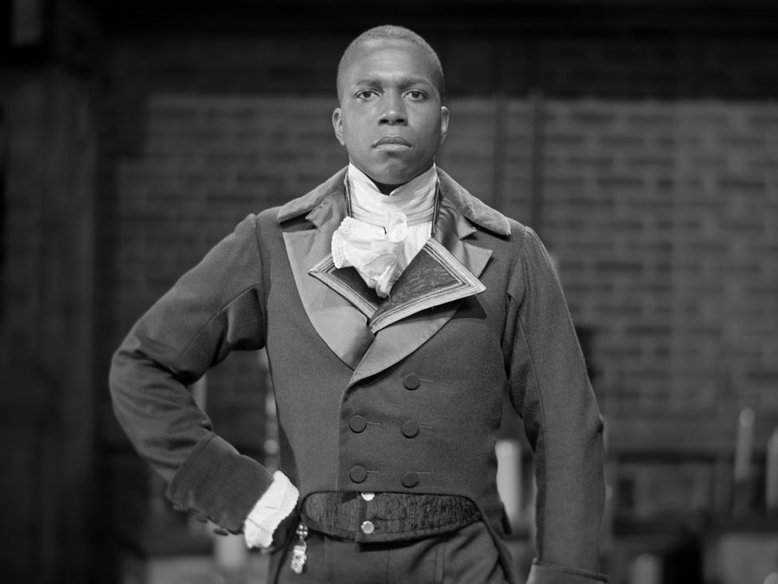

Aaron Burr as portrayed by Leslie Odom Jr. in the musical “Hamilton.” Photo by Josh Lehrer.

Newark-born Aaron Burr became a hero in the Revolution in September 1776 when he saved his brigade from capture by the invading British, skillfully retreating from lower Manhattan to Harlem. Among the officers saved by the valiant Burr: Alexander Hamilton, whom Burr would slay in an infamous duel in Weehawken some 28 years later.

COLD COMFORT

The Wick House Farm at Jockey Hollow, one of the sites at Morristown National Historic Park. Photo by Lauren Bowers

Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, is synonymous with frigid winters, thanks to General George Washington’s winter encampment there in 1777-78. But Washington’s band of brothers endured the three other winters during the War of Independence at New Jersey outposts in Morristown, Middlebrook (near Bound Brook) and again in Morristown. In fact, the winter of 1779-80 in Morristown was considered even more bone-chillingly brutal for Washington’s army than the months they endured at Valley Forge.

FIGHTING STATE

A reenactment of the Battle of Monmouth at Monmouth Battlefield State Park. Photo courtesy of Flickr Creative Commons: zhengxu.

The American Revolution may have started in Massachusetts (Lexington and Concord) and ended in Virginia (Yorktown), but no colony was the site of more battles vs. the British than New Jersey. According to at least one accounting, there were 296 engagements in New Jersey during the eight-year war.

STRONG AS AN OAK

The early morning fog over the Princeton Battlefield, a section of the Washington-Rochambeau trail route. Courtesy of Flickr/Creative Commons.

General Hugh Mercer suffered one of the more famous deaths in the Revolution. Mortally wounded at the Battle of Princeton on January 3, 1777, the Scottish-born officer refused to leave battlefield. As the legend goes, Mercer sat against the base of a massive oak and rallied his troops to victory. Mercer died of bayonet wounds nine days later—but the oak tree that gave him strength stood until March 2000 when a fierce storm took its final toll. The tree became the emblem of Princeton Township and a key element of the county seal of Mercer County—which, of course, was named for the general. Mercer’s descendants included World War II General George S. Patton and the lyricist Johnny Mercer (“Moon River”; “Hooray for Hollywood”).

HOLD THE FORT

General Charles Lee. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The Bergen County borough of Fort Lee is named for Revolutionary War General Charles Lee. That’s quite an honor for a soldier who in July 1778 was court-martialed after retreating in the face of the enemy during the Battle of Monmouth. Among the charges: disrespecting his commander—none other than George Washington. Found guilty, Lee was relieved of his command for a year. Lee, who earlier had been captured and released by the British, also was rumored to have passed secrets to the enemy—as portrayed in the AMC TV series Turn.

POURING IT ON

Molly Pitcher on the battlefield. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Perhaps the most famous woman in the American Revolution was New Jersey’s own Molly Pitcher. Alas, that wasn’t her real name. Pitcher was born Mary Ludwig in Trenton. Like many women of the era she remained near her soldier-husband, William Hays, to aid on the battlefield. She earned her nom de guerre bringing pitchers of water to the troops on a sweltering June day at the Battle of Monmouth. But her real heroism came that day when her husband collapsed at his cannon and she took his place. According to the legend, she was nearly hit by a British cannon shot that went between her legs.

STIRLING IS GOLDEN

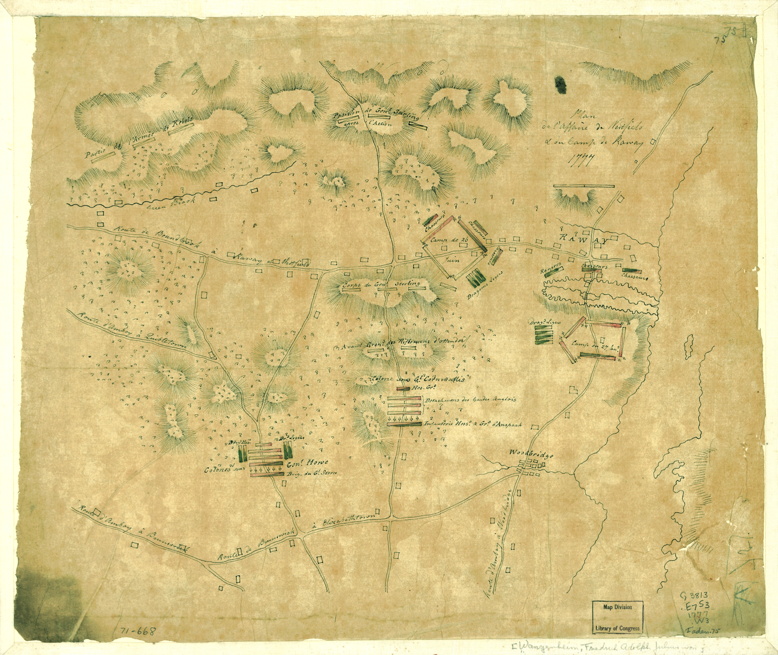

A contemporary Hessian map depicting the positions in the Battle of Short Hills. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

History calls it the Battle of Short Hills, but we know better. The brief engagement—a strategic victory for the Colonists—actually was fought in Scotch Plains and Edison. But why haggle over geography? During the battle, Brigadier General William Alexander’s badly outnumbered division stalled the Brits long enough to let Washington’s main army escape to fight another day. Alexander (aka Lord Stirling) was born in New York, but had major Jersey cred—thanks to his marriage to Sarah Livingston, sister of our state’s first governor, William Livingston. The town of Stirling is named for Lord Stirling, as is Lord Stirling Park in Basking Ridge, site of the family’s former estate.