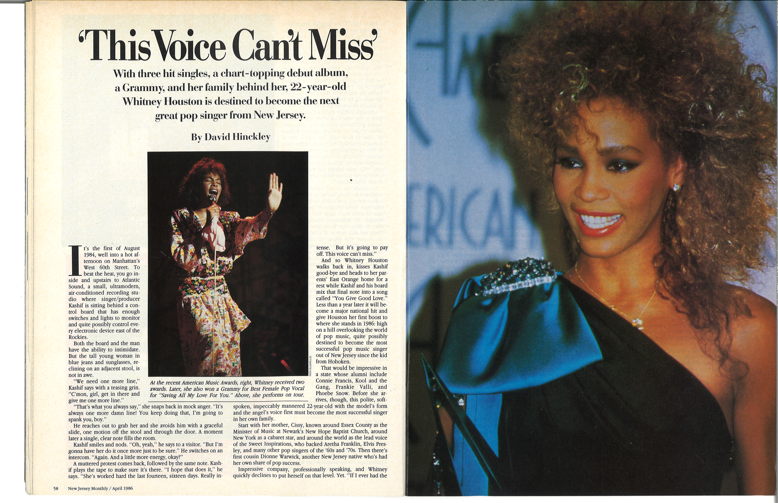

It’s the first of August 1984, well into a hot afternoon on Manhattan’s West 60th Street. To beat the heat, you go inside and upstairs to Atlantic Sound, a small, ultramodern, air-conditioned recording studio where singer/producer Kashif is sitting behind a control board that has enough switches and lights to monitor and quite possibly control every electronic device east of the Rockies.

Both the board and the man have the ability to intimidate. But the tall young woman in blue jeans and sunglasses, reclining on an adjacent stool, is not in awe.

“We need one more line,” Kashif says with a teasing grin. “C’mon, girl, get in there and give me one more line.”

“That’s what you always say,” she snaps back in mock anger. “It’s always one more damn line! You keep doing that, I’m going to spank you, boy.”

He reaches out to grab her and she avoids him with a graceful slide, one motion off the stool and through the door. A moment later a single, clear note fills the room.

Kashif smiles and nods. “Oh, yeah,” he says to a visitor. “But I’m gonna have her do it once more just to be sure.” He switches on an intercom. “Again. And a little more energy, okay?”

A muttered protest comes back, followed by the same note. Kashif plays the tape to make sure it’s there. “I hope that does it,” he says. “She’s worked hard the last fourteen, sixteen days. Really intense. But it’s going to pay off. This voice can’t miss.”

And so Whitney Houston walks back in, kisses Kashif good-bye and heads to her parents’ East Orange home for a rest while Kashif and his board mix that final note into a song called “You Give Good Love.” Less than a year later it will become a major national hit and give Houston her first boost to where she stands in 1986: high on a hill overlooking the world of pop music, quite possibly destined to become the most successful pop music singer out of New Jersey since the kid from Hoboken.

That would be impressive in a state whose alumni include Connie Francis, Kool and the Gang, Frankie Valli, and Phoebe Snow. Before she arrives, though, this polite, softspoken, impeccably mannered 22-year-old with the model’s form and the angel’s voice first must become the most successful singer in her own family.

Start with her mother, Cissy, known around Essex County as the Minister of Music at Newark’s New Hope Baptist Church, around New York as a cabaret star, and around the world as the lead voice of the Sweet Inspirations, who backed Aretha Franklin, Elvis Presley, and many other pop singers of the ’60s and ’70s. Then there’s first cousin Dionne Warwick, another New Jersey native who’s had her own share of pop success.

Impressive company, professionally speaking, and Whitney quickly declines to put herself on that level. Yet. “If I ever had the kind of success as Dionne…,” she’ll say, and that’s as far as she gets. She rolls her eyes up and laughs disbelievingly. “Right now I can’t imagine it.”

Although the deference is no act, her own success has not been inconsequential. In the year since her self-titled first album was released, it has sold almost three million copies. “You Give Good Love” was a number-three national single, and the two that followed, “Saving All My Love For You” and “How Will I Know,” both reached number one. An eight-month tour that began in small cabarets ended with two sellouts at Carnegie Hall.

In January, she won two American Music Awards, which are voted by the public. In February, by a vote of her peers, she won her first Grammy, Best Female Pop Vocal for “Saving All My Love For You.” That came after being nominated for three other Grammys (Album of the Year, Best Female R&B Vocal, and best R&B Song) and in spite of being barred from the Best New Artist category—an award she almost certainly would have won—because she had sung duets on albums by Jermaine Jackson and Teddy Pendergrass in a previous Grammy year. She’s now in the studio recording her next album now in the studio recording her next album other major hit is probably as safe a bet as there is in the flaky music business.

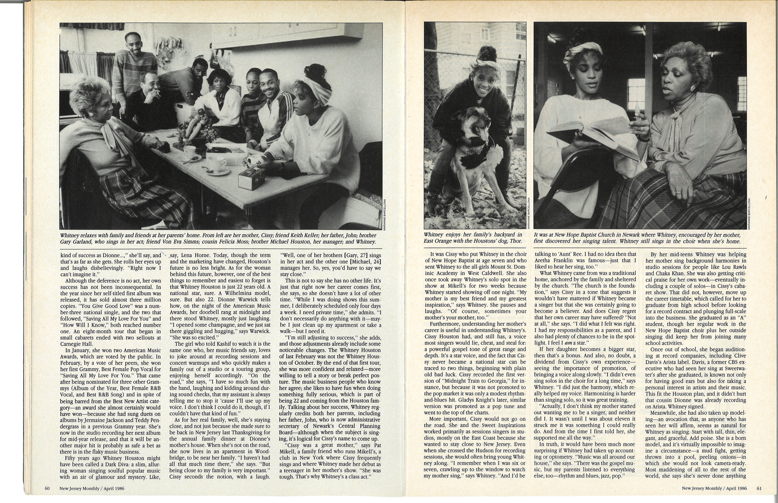

Fifty years ago Whitney Houston might have been called a Dark Diva: a slim, alluring woman singing soulful popular music with an air of glamour and mystery. Like, say, Lena Horne. Today, though the term and the marketing have changed, Houston’s future is no less bright. As for the woman behind this future, however, one of the best things to remember and easiest to forget is that Whitney Houston is just 22 years old. A national star, sure. A Wilhelmina model, sure. But also 22. Dionne Warwick tells how, on the night of the American Music Awards, her doorbell rang at midnight and there stood Whitney, mostly just laughing. “I opened some champagne, and we just sat there giggling and hugging,” says Warwick. “She was so excited.”

The girl who told Kashif to watch it is the same one who, her music friends say, loves to joke around at recording sessions and concert warmups and who quickly makes a family out of a studio or a touring group; enjoying herself accordingly. “On the road,” she says, “ I have so much fun with the band, laughing and kidding around during sound checks, that my assistant is always telling me to stop it ’cause I’ll use up my voice. I don’t think I could do it, though, if I couldn’t have that kind of fun.”

As for her real family, well, she’s staying close, and not just because she made sure to be back in New Jersey last Thanksgiving for the annual family dinner at Dionne’s mother’s house. When she’s not on the road, she now lives in an apartment in Wood-bridge, to be near her family. “I haven’t had all that much time there,” she says. “But being close to my family is very important.” Cissy seconds the notion, with a laugh. “Well, one of her brothers [Gary, 27] sings in her act and the other one [Michael, 24] manages her. So, yes, you’d have to say we stay close.”

This is not to say she has no other life. It’s just that right now her career comes first, she says, so she doesn’t have a lot of other time. “While I was doing shows this summer, I deliberately scheduled only four days a week. I need private time,” she admits. “I don’t necessarily do anything with it—maybe I just clean up my apartment or take a walk—but I need it.

‘I’m still adjusting to success,” she adds, and those adjustments already include some noticeable changes. The Whitney Houston of last February was not the Whitney Houston of October. By the end of that first tour, she was more confident and relaxed—more willing to tell a story or break perfect posture. The music business people who know her agree; she likes to have fun when doing something fully serious, which is part of being 22 and coming from the Houston family. Talking about her success, Whitney regularly credits both her parents, including her father, John, who is now administrative secretary of Newark’s Central Planning Board—although when the subject is singing, it’s logical for Cissy’s name to come up.

“Cissy was a great mother,” says Pat Mikell, a family friend who runs Mikell’s, a club in New York where Cissy frequently sings and where Whitney made her debut as a teenager in her mother’s show. “She was tough. That’s why Whitney’s a class act.”

It was Cissy who put Whitney in the choir of New Hope Baptist at age seven and who sent Whitney to the all-girls Mount St. Dominic Academy in West Caldwell. She also once took away Whitney’s solo spot in the show at Mikell’s for two weeks because Whitney started showing off one night. “My mother is my best friend and my greatest inspiration,” says Whitney. She pauses and laughs. “Of course, sometimes your mother’s your mother, too.”‘

Furthermore, understanding her mother’s career is useful in understanding Whitney’s. Cissy Houston had, and still has, a voice most singers would lie, cheat, and steal for: a powerful gospel tone of great range and depth. It’s a star voice, and the fact that Cissy never became a national star can be traced to two things, beginning with plain old bad luck. Cissy recorded the first version of “Midnight Train to Georgia,” for instance, but because it was not promoted to the pop market it was only a modest rhythm-and-blues hit. Gladys Knight’s later, similar version was promoted as a pop tune and went to the top of the charts.

More important, Cissy would not go on the road. She and the Sweet Inspirations worked primarily as sessions singers in studios, mostly on the East Coast because she wanted to stay close to New Jersey. Even when she crossed the Hudson for recording sessions, she would often bring young Whitney along. “I remember when I was six or seven, crawling up to the window to watch my mother sing,” says Whitney. “And I’d be talking to ‘Aunt’ Ree. I had no idea then that Aretha Franklin was famous—just that I liked to hear her sing, too.”

What Whitney came from was a traditional home, anchored by the family and sheltered by the church. “The church is the foundation,” says Cissy in a tone that suggests it wouldn’t have mattered if Whitney became a singer but that she was certainly going to become a believer. And does Cissy regret that her own career may have suffered? “Not at all,” she says. “I did what I felt was right. I had my responsibilities as a parent, and I also had plenty of chances to be in the spotlight. I feel I am a star.”

If her daughter becomes a bigger star, then that’s a bonus. And also, no doubt, a dividend from Cissy’s own experience—seeing the importance of promotion, of bringing a voice along slowly. “I didn’t even sing solos in the choir for a long time,” says Whitney, “I did just the harmony, which really helped my voice. Harmonizing is harder than singing solo, so it was great training.

“Actually, I don’t think my mother started out wanting me to be a singer, and neither did I. It wasn’t until I was about eleven it struck me it was something I could really do. And from the time I first told her, she supported me all the way.”

In truth, it would have been much more surprising if Whitney had taken up accounting or optometry. “Music was all around our house,” she says. “There was the gospel music, but my parents listened to everything else, too-rhythm and blues, jazz, pop.”

By her mid-teens Whitney was helping her mother sing background harmonies in studio sessions for people like Lou Rawls and Chaka Khan. She was also getting critical praise for her own work—eventually including a couple of solos—in Cissy’s cabaret show. That did not, however, move up the career timetable, which called for her to graduate from high school before looking for a record contract and plunging full-scale into the business. She graduated as an “A” student, though her regular work in the New Hope Baptist choir plus her outside singing did keep her from joining, many school activities.

Once out of school, she began auditioning at record companies, including ‘Clive Davis’s Arista label. Davis, a former CBS executive who had seen her sing at Sweetwater’s after she graduated, is known not only for having good ears but also for taking a personal interest in artists and their music. This fit the Houston plan, and it didn’t hurt that cousin Dionne was already recording on Arista. Whitney signed.

Meanwhile, she had also taken up modeling-an avocation that, as anyone who has seen her will affirm, seems as natural for Whitney as singing. Start with tall, thin, elegant, and graceful. Add poise. She is a born model, and it’s virtually impossible to imagine a circumstance—a mud fight, getting thrown into a pool, peeling onions—in which she would not look camera-ready. Most maddening of all to the rest of the world, she says she’s never done anything special to stay that way. “I’ve never been on any diets or anything,” she says, laughing. “I try to eat healthy food—like sometimes honey for my throat—but mostly, I have so much energy I just burn food right up.”

She signed first with the Click agency and subsequently moved to high-powered Wilhelmina. She appeared in national ad campaigns for Revlon and Sprite, though most of her work was in fashion spreads for teen magazines like Young Miss and Seventeen. Not surprisingly, she hasn’t had much oncamera time lately. “I like modeling,” she says. “But it’s a sideline, really. It’s not something like singing, where I really believe in everything about it. It was something I could do, so I did. But singing always comes first.”

As it happens, Arista found a way to combine the two. As a promotion for her first album, the company issued a poster-sized calendar that includes Whitney walking a horse in the surf, Whitney poised on a tree limb, Whitney in a bathing suit, and Whitney looking at the camera. It could have been one of the all-time great show-biz hedges; even if the album had sold only 200 copies, the calendar still could have gone double platinum.

Not that Whitney’s voice needed help. Despite its gospel roots, she often sings in more of a pop style than Cissy does. Her sound is closer to that of cousin Dionne, perhaps, but in any case it’s tailor-made to clear the still-high barriers between the lucrative Top 40 “pop” market and the prestigious, but restricted, black/soul/rhythm-and-blues market.

Ironically, this can present a problem. Crossover black artists like Michael Jackson are often accused of “forgetting the black market” once they’ve had pop success. Houston has faced no serious criticism in this area so far, although the fact that her record made its first substantial impact on the black charts raises the possibility that she could hear some complaints in the future. Nor is there any sign that she’s forgetting where she came from. When she’s home she still sings with the church choir, and late last year she joined a group that included mostly black street music artists to do a Martin Luther King tribute called “King Holiday.”

Conversely, the fact that Arista promoted her in the pop market from the start should prevent a common, related problem. “If you’re a woman and you’re black,” says Patti LaBelle, “most companies assume you’re an R&B singer. I’ve fought that for 25 years.”

Houston will not have to. Her pop promotion was hardly an accident, of course. Her first album was allotted $250,000 by Arista, an enormous budget for a new artist and not an investment a company would make for only one market. It was recorded over eighteen months with four producers (Kashif, Jermaine Jackson, Michael Masser, and Narada Michael Walden) from the chosen mold—black background, pop style—and Whitney says that Davis took a personal hand in selecting the songs. “It’s uncanny how much Clive and I think alike,” she says. “If he likes a song, it’s almost 100 percent sure I will, too.”

While her album was being pieced together, Arista introduced her to the record world through the duets with Jackson and Pendergrass. Though doing these recordings probably cost her the Best, New Artist Grammy, they did the job, establishing her sophisticated pop/urban sound.

Nor does Whitney see anything dire about calculated marketing. I’m grateful,” she said last January, on the eve of the album’s release. “It takes the pressure off. I know some people say I’m going to be a star and all that, but I don’t even have to think about that because I know everything’s been done and what’s going to happen will.”

Still, she was a little nervous when she introduced that first album at Sweetwater’s, a small New York cabaret she had often played with her mother. She sang most of the album straight through, doing a particularly impressive duet of “You Give Good Love” with brother Gary, and she paused only to thank her family and Clive Davis.

After the debut she hit the road for small club dates, the opening spot at arena shows with pop/soul star Luther Vandross, and then the Carnegie Hall finale, where the audience included fellow New Jersey resident Eddie Murphy, New York Mayor Ed Koch, and pop stars Ashford and Simpson. For a singer, there are worse scenarios.

The only hitch in the carefully crafted plan, in fact, is the speed with which it developed. “If you’d told me a year ago that I’d have had a top-five song or album in the country, I’d have said, ‘Yeah, sure, tell me another one,’ ” she says. She acknowledges that quick success did force her to learn things on the fly, such as not to sing with swollen glands. “I did it one night in Los Angeles and the next morning I couldn’t say a word. I finally called Dionne in a total panic. Her doctor told me I couldn’t sing for a week. I had to cancel a show, which I hated to do. It felt totally unprofessional, even though I wasn’t faking. It was the worst night of my life.”

Then there was the Ann Landers incident. In a reply to a letter about tasteless rock lyrics last summer, Landers cited “You Give Good Love”—whose title is far more catchy than lascivious—as a song that parents might want to scrutinize before their children were allowed to listen. “I didn’t know it until someone pointed it out a few days later,” says Houston. “I thought it was funny. I think Miss Landers responded to a question after just seeing the title. If she’d heard it, I think she’d have realized her attitude was more suggestive than the song.”

More significantly, she has had to learn how to put a show together, which is not as easy as it sounds. “Even twenty minutes is hard at first,” says Gladys Knight, who faced the problem 30 years ago. “Which songs you do, in what order. How you pace it. Until you have more material, you sweat.”

Indeed, after a show at New York’s Bottom Line early on her tour, Billboard magazine’s Nelson George suggested that Houston’s no-frills cabaret-style show needed more work before it would be fully effective in concerts. And the Carnegie Hall nights, triumphant as they were, showed that such concerns had not been fully erased. What she did at Carnegie was largely the same show she had done eight months earlier at Sweetwater’s, padded with musical flourishes and pleasant but superfluous comments that ultimately slowed the show down. Her new act was now twice as long as the original show with little more of the main attraction: her voice.

Though another album should provide enough additional material to ease this problem, the larger question remains of where her career will ultimately head. She plans to keep singing pop songs (“I don’t see why not”), and with her looks and poise, it’s hard to believe that someone isn’t planning movies and other visual projects as well (she’s already doing a Diet Coke ad). But she has other choices, such as either finding a lucrative, safe spot on the class club circuit or taking some musical chances.

For now, the path looks conservative. Whitney says the songs on her second album “will probably be the same style” as on her first. Most of the same producers will be back, and Davis is screening songs again. For her own part, not many 22-year-olds have 25-year plans and neither does Houston. “I expect to be singing a long time, and I want to do songs that will last. I’m attracted to words. But for now, I’m taking it one step at a time. Clive is great about that. He doesn’t say, ‘Okay, next you gotta have a Thriller that sells 30 million copies’ or anything.”

Are there particular projects she’d like to do? “Sure, someday I’d like to record with Dionne and my mother. I’d love to do a gospel album, because that’s really where my roots are. No matter what I sing, I could never take the gospel out of my voice.

“Right now I don’t think there’s any ‘expected thing’ from me. Every show I can feel there are people in the audience who are surprised, who are saying, ‘Who is that skinny girl with those skinny legs making those great big sounds?’ I think I’m a combination of visual and vocal effects now, and I want that to continue.”

When you’re 22 and things have gone as well as they have for Whitney Houston, you figure the streak will continue. “My mother always said you are what’s bred into you,” Whitney says.

“And so far, I think she’s been right.”

New Jersey resident David Hinckley writes about music and entertainment.