Before Matt Stagliano became a spokesman for the New Jersey Education Association earlier this year, he spent seven years as a high school teacher in Camden County. He left the classroom and took the corporate post in Trenton, where the NJEA is headquartered, not because things went south with the students he still calls “his kids,” but partly because of a state requirement he considers misguided: PARCC testing.

“Like at all public schools, my kids had to take PARCC”—an acronym for the Partnership for Assessment for Readiness for College and Careers. “It was one of the most demoralizing experiences I ever had,” says Stagliano, who taught English at Camden County Vocational Technical School in Sicklerville and lives in Washington Township.

“These were kids I was so impressed with, who I thought were brilliant and generally thought the world of. And after that test some of them came up to me and said, ‘Mr. Stag, am I stupid?’ I remember one kid in particular who started his freshman year not doing so well, and by the time he was a junior he had worked his way up to honor roll and was an athlete and the whole thing. He took the test and it knocked the wind out of his sails.”

PARCC testing became mandatory in 2014 for New Jersey students in grades 3 through 11, as a way to align with the Common Core standards, a set of learning goals established to ensure students were being adequately prepared for college. The standards were adopted across the country starting in 2010, encouraged by funding from the Obama administration. But then came a backlash, with many states dropping the tests or ignoring the standards altogether. In New Jersey, many students exploited a loophole that allowed them to opt out of PARCC amid concerns about testing procedures and the generally dismal results.

Recently, however, New Jersey has moved back toward institutionalizing the tests. In August, the New Jersey State Board of Education voted to require future high school students to pass a pair of PARCC tests in order to graduate. Current high schoolers are not affected by the decision, but beginning with the class of 2021, students will be required to pass the PARCC Algebra 1 exam and the 10th-grade English exam. This year, just 41 percent of students statewide passed the Algebra 1 test, and 44 percent passed the 10th-grade English exam.

Additional PARCC tests in English and math will continue to be given to children in grades 3 through 11. However, for now, the students will be allowed to take alternative tests. Fewer than 50 percent of students in New Jersey met expectations across the nine grades of math and language tests in the 2014-2015 school year.

According to data compiled by Julia Sass Rubin, an associate professor at Rutgers’s Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy in New Brunswick, 70,000 New Jersey public school kids were absent on test days or “opted out” of the English Language Arts tests in 2015-2016 at the urging of frustrated, concerned parents. An official count is not yet available from the state Department of Education. The prior school year, 135,000 students didn’t take the tests, according to Rubin.

Assuming the new graduation requirement goes unchallenged, one option remains for students due to graduate in 2021 and beyond. These students can seek approval of a “portfolio of work”—if they otherwise meet all graduation criteria except the assessment requirements. But that option has not appeased some detractors of the high-stakes test, Stagliano among them.

“Advocating for students comes with the territory of being an educator,” he says. “We believe the state should return testing to the teachers, because we’re testing experts and we know what constitutes a good, fair test.” PARCC, he continues, is “a hot-button issue among our 203,000 members,” most of them teachers and education support professionals, including assistants and program coordinators. “The majority is very opposed to the testing.”

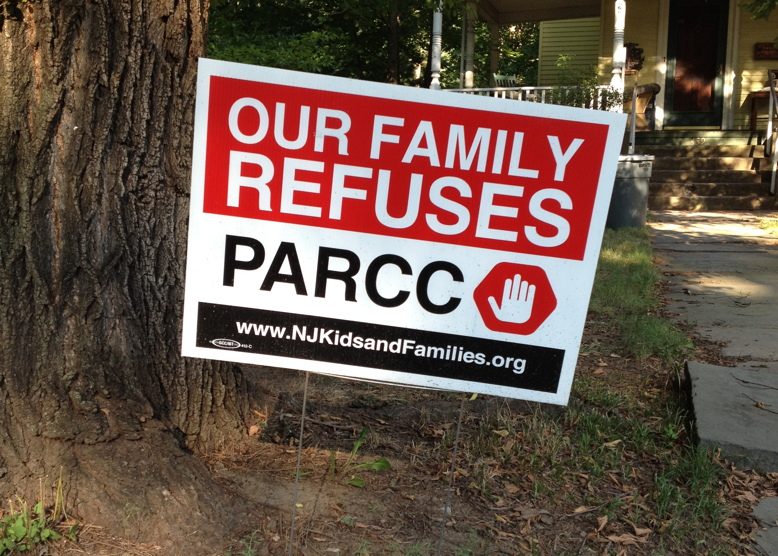

They’re not the only ones. Parent advocacy groups are also opposed, and determined.

The Bloustein School’s Rubin is a founder of Save Our Schools NJ, an all-volunteer group formed in 2010 to organize parents to advocate in support of public education. The group has amassed a mailing list of 31,000. Of PARCC, Rubin says, “parents everywhere, in every one of New Jersey’s school districts, are fit to be tied over this.”

The Save Our Schools website lists “12 Reasons We Oppose the PARCC Test.” Among other things, the list says the tests are “poorly designed and confusing.” Further, it says PARCC is “diagnostically and instructionally useless” and “distorts curricula and teaching,” with preparation for the tests replacing actual learning. Save Our Schools also decries the cost of the tests, and their experimental nature. Ultimately, says the website, the tests “are designed to brand the majority of our children as failures.”

Rubin has her own conclusion. “What this test is doing is ruining children’s lives,” she says. “It’s creating a school-to-prison pipeline.” She says PARCC is a way to condemn, or at least discourage, underprivileged kids in poor school districts. “My issue with PARCC, and with all high-stakes standardized tests, is that they are a faulty measure of learning that reflect family income rather than student knowledge, and that they particularly penalize students living in poverty, students with special needs and students are English-language learners.” She adds: “It’s not just that I believe this, it’s that research consistently shows that standardized test scores are lower on average” for such students.

Earlier this year, the Education Law Center, a Newark-based public-interest law firm, sued the DOE, accusing the state of—among other things—failing to provide enough pathways to graduation for kids at different achievement levels. The suit was settled in May with the state broadening what it would accept for graduation. Essentially, that suit gave new prominence to the “portfolio of work” alternative to PARCC that will rescue some would-be graduates.

But putting together those portfolios will be costly and labor-intensive for school districts, Rubin says—even resulting in some students “missing weeks of class.” And the suggested content of the portfolios has yet to be established.

This alternative aside, Rubin says the testing is just too rigorous.

“In effect the governor is asking kids to run a four-minute mile to graduate high school. The idea is that if you raise the bar, students will rise to meet it. But how many kids do you know who can run a four-minute mile?,” Rubin says. Especially, she adds, when they may not even have the resources to buy sneakers.

It’s unclear why New Jersey has embraced PARCC as a graduation requirement even as other states have moved away from it. According to Matt Vanover, a PARCC spokesman, 10 states and the District of Columbia participated in the first year of PARCC testing. In the 2015-16 school year, seven states and the District of Columbia fully participated. In the new school year, eight states and D.C. (along with the Bureau of Indian Education and the Department of Defense school system) are expected to participate. New Jersey, New Mexico and Maryland are the only states that have made PARCC a future graduation requirement.

PARCC’s administrators have not been deaf to criticism. After the first year, testing time was cut by 90 minutes, and the tests were administered once in a single two-week window, rather than in two testing windows months apart.

According to the DOE, when compared to prior standardized tests, PARCC assessments provide more thorough academic measurement, more comprehensive feedback for parents, improved instruction and reduced college remediation. What’s more, they use current technology (most students take the PARCC exams on a computer).

“New Jersey has had statewide tests for decades, and they serve as a small but important part of a student’s overall education,” says David Saenz, spokesman for the Department of Education. “Generally, PARCC tests account for less than one percent of a student’s average instruction time in a school year, based on a required 180 days school year, and the average seven-hour school day.”

This school year, districts can choose when to give the tests within a six-week window; it is expected that districts could finish testing for all grades and levels within two weeks, and individual students could complete testing in a few days. Tests in grades three to eight will be given between April 4 and May 13. Tests in high schools will start a week later and will be conducted until May 20. Some high schools with block schedules can administer the tests between April 25 and June 3. The state is expected to provide test results by early summer 2017, as it did this year. That’s about six months earlier than in the initial year.

As for the costs, Saenz says, “we have spent less on PARCC per pupil than under NJASK/HSPA,” PARCC’s standardized forerunners. The per-student cost for the previous tests in 2013-2014 was $28.50; in 2014-2015, PARCC cost $24.10 per student, according to Saenz.

But none of that is quieting the critics.

Julie Larrea Borst, of Allendale, is the mother of a special-ed high school student and a moderator of the New Jersey Opt Out of Standardized Tests—New Jersey Facebook page. The page has 10,000 followers, Borst says.

“We have people from all over the state,” says Borst. “It doesn’t matter if you’re from a sparkly district or a poor one, or if you’re liberal or conservative. People have so many reasons for concern about this, from how much time is being taken away from actual teaching to teachers being evaluated on how kids are scoring to people like me, a special-ed parent who knows my daughter does not operate at grade level, so what’s the point of giving her a test on material she’s never going to see?

“There are so many questions,” she continues. “Why exactly are we doing this? The answer is we don’t really know.”

REFUSE to support this test! Go here for help – http://www.optthemout.com/, http://www.fairtest.org, http://www.saveoutschoolsnj.org, http://www.njkidsandfamilies.org