On a small bare stage—in a black box of a room with no proscenium and as yet no grandstand of seats—the cast and crew of August Wilson’s “King Hedley II” are in the earliest stages of rehearsal.

Though the actors are in street clothes, some still holding scripts, the atmosphere as they run lines is charged with the desperation that courses through the play and triggers its shattering yet mystically hopeful conclusion.

The bare room is the 110-seat Marion Huber Theater, the smaller of the two performing spaces at Two River Theater in Red Bank. Brandon J. Dirden, the play’s director, stands behind a table just beyond the performance area, leaning forward, hands pressing the tabletop, listening intently.

When he speaks, he speaks quietly, waiting until the portion of the scene being worked on has ended. At this early point he is working out the blocking—where characters stand and move in relation to each other—which establishes what he calls “lanes” that direct the audience’s attention and create spaces and moments for meaning to arise from words and actions. He modestly likens directing “to being a traffic cop.”

Dirden, 39, has a muscular build and a languid gait that contains a hint of swagger. When he crosses the line of tape marking the boundary of the acting space, his authority travels with him. But he underplays it. At one point he couches a suggestion to actor Blake Morris, playing the title character, as an “offering.” The character, who goes by King, is an agitated young man, about to take a fateful action.

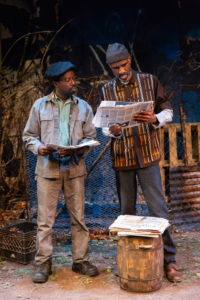

Blake Morris (King Hedley II) and Harvy Blanks (Elmore, King’s mother’s former lover). Courtesy of T. Charles Erickson

“Work on channeling this energy, instead of going off in every direction,” Dirden counsels him. “Is that helpful? You don’t have to bounce around like a football player about to take the field. You can stand like a very centered warrior.”

Steeped in the works of Wilson, Dirden is an Obie-Award winning actor who made his directorial debut with Wilson’s “Seven Guitars” at Two River, appeared in Wilson’s “Jitney” and starred in Wilson’s “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom” here and has appeared in three other plays in Wilson’s 10-play Century Cycle. He was in the Broadway cast of “Jitney” that won the 2017 Tony Award for Best Revival of a Play. Also at Two River he starred in the 2017 revival of Lorraine Hansberry’s “A Raisin in the Sun.” On Broadway, he played Martin Luther King Jr. opposite Bryan Cranston’s LBJ in All The Way. On FX’s The Americans he was FBI Agent Dennis Aderholt.

“Hedley” brings Two River Theater to the halfway point in its commitment to present all 10 plays in Wilson’s epochal portrait of African-American life, the Century Series. (Previews begin Saturday, November 10. The show opens Friday, November 16, and runs through Sunday, December 16.)

Each play is set in a different decade of the 20th Century, and all but one are set in the Hill District, the black neighborhood of Pittsburgh, where Wilson grew up. The cycle absorbed Wilson for roughly the last two decades of his all-too-brief life. During that creative burst, two of the plays—”Fences” (set in 1957, completed in 1987) and “The Piano Lesson” (set in 1936, completed in 1990) won Pulitzer Prizes. Wilson finished the final piece (“Radio Golf,” set in 1997) in 2005—the year he died, at 60, just months after being diagnosed with cancer.

Until now, Two River has presented the plays on its 342-seat main stage. They began in 2012 with “Jitney” (1977, comp. 1982). In 2013 came “Two Trains Running” (1969, comp. 1991), followed in 2015 by “Seven Guitars” (1948, comp. 1995) and in 2016 by “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom” (1927, comp. 1984).

Brittany Bellizeare (Tonya, King’s wife). Courtesy of T. Charles Erickson

During a break in the rehearsal, Dirden talked about his decision to present it in the smaller space.

“I wanted,” he said, “to honor the audiences who have been so faithful taking this journey with us. I want to give them an immediacy you can’t get in a larger theater. I want the audience to really feel the pressure the characters are under. When we feel that, it gives us access to empathy. Palpable danger exists in this play, but there’s not a lot of [physical] movement. The movement is in the words.”

Indeed, dynamic language—rapid-fire jousts, wrenching soliloquies, curses, blessings, visions, tall tales comic and prophetic—drives every Wilson script. When actual music is heard, it’s usually some form of the blues, which Wilson treasured.

In “Hedley” it is 1985, urban renewal is turning homes in the Hill District into empty shells, the steel industry is foundering and jobs are scarcer than ever, especially for African-Americans. King and his buddy, Mister (Charlie Hudson III), are young men resorting to dubious schemes to salvage their dream of owning a video store. King has recently finished serving time for the murder of a man who slashed his face in a quarrel, leaving him with a permanent scar. His wife, Tonya (Brittany Bellizeare), is 35 and pregnant with a second child, one she does not want to bring into a world so hopeless.

Hovering over this and other turmoil is the news of the death of Aunt Ester, an almost mythological character spoken of reverentially in two of the plays but actually seen onstage only in the series opener, “Gem of the Ocean” (set in 1904, premiered 2003). She is understood to be 366 years old, a fount of wisdom who has literally seen it all, from the Middle Passage across the ocean to slavery to the present.

The significance of Ester’s unexpected death is foreshadowed in “Hedley’s” prologue, in which the off-kilter visionary Stool Pigeon (Brian D. Coats) bemoans, “Times ain’t nothing like they used to be. Everything done got broke up…The people wandering all over the place. They got lost. They don’t even know the story of how they got from tit to tat…The people need to know the story. See how they fit into it. See what part they play.”

The Century Cycle as a whole stands as a monument to the need to embrace one’s history, its deepest wounds as well as its balms and joys.

In our conversation after the rehearsal, Dirden spoke ruefully of “the devastating encroachment by this thing called eminent domain. A senior citizen high-rise for years was the displacement of these people. Like, ‘You’ll be fine, you’ll be taken care of.’ Meanwhile, they’re going to take all this land.

Elain Graham (Ruby, King’s mother). Courtesy of T. Charles Erickson

“That’s a bleak reality that happened not just in Pittsburgh but in major cities all over this country. It happened in Houston [Dirden’s hometown]. The Third Ward and Fifth Ward in Houston once were very prosperous African-American communities. Then it was, ‘Pull out resources, pull out services, and watch this thing collapse on itself.’

“When you do that to a group of people, to somebody’s livelihood and habitat, what do you expect to come from that?

“At the same time, we live in a country that has promised life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. Those two things are in direct opposition to each other. It’s like, ‘You say I’m equal, responsible for my own destiny. You say I have the freedom to be prosperous. But the very place I lived in, not as a renter, but the place I owned—you told me home ownership was the key to wealth and stability. And now you say it’s worth only half of what I paid for it.’

“You see what a tinderbox that creates. This brings us to ‘King Hedley II’ in 1985 and a stark reality. That the American dream has failed Americans.

“But August doesn’t stop there. Not to give away the ending, but I’m struck by the hope that August injects in this play in its final moments. There’s a lot of origin stories for cultures throughout history, where a birth of a new generation is made from a sacrifice. The death of something provides life for something else.

“What I take from this play is that this is necessary. There is something else to come from this.”

Returning to the subject of the performance space, he said, “There is another reason I was adamant about putting it in the smaller theater. A lot of August’s plays are set in a period that is not now. We are able to look at it almost as a museum piece. But in 1985, these are characters you can meet walking up the street today. I want to capture the immediacy of this story.

Charlie Hudson III (Mister, King’s buddy) and Brian D. Coats (Stool Pigeon, a visionary). Courtesy of T. Charles Erickson

“In a smaller space, its harder for me to check out and say, ‘Okay, it’s just theater, it’s not really happening.’

“So we spend two and a half hours with this bleakness to try to snap into the promise of something bigger and brighter coming. And that’s what I hope to do with this production.”

Earlier that afternoon as he ended the rehearsal, Dirden, as is his custom, joined hands in a circle with the cast and crew in the center of the stage. He thanked them for their work and dedication. Then he asked, “Does anyone have a word?”

A few spoke up. “Bless,” said Charlie Hudson, adding, “Learn.” People nodded, voiced assent.

Dirden concluded with a prayer that took a quizzical turn at the end. “We thank the creator for the ability and strength to do this work…and to be judged and found not guilty, but convicted.”

Then they all raised their clasped hands high and shouted,”This is August Wilson’s King Hedley the Second!”