After the pandemic devastated nursing homes around the country, many elderly people wanted to find a different way of living out their golden years—one that would keep them in their homes and communities.

That’s just one reason why Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs)—small, single housing units located on the properties of larger, single-family homes—have become popular in New Jersey.

“Many [elderly] people want to age in place. They want to keep the same doctors and houses of worship and neighborhoods. Disruptions can be difficult for older people to adjust to,” says Ann Lippel, a Montclair Gateway Aging in Place board member who has been advocating for ADUs in the Essex County town since 2015.

After more than a decade of discussion, Montclair finally passed an ADU ordinance in February, making it legal to have one of these tiny homes. Montclair joins a short list of other municipalities around the state that have passed ADU ordinances, including Princeton, Maplewood, East Orange and Bradley Beach. Restrictions regarding things such as square footage and number of stories an ADU can have vary by town.

An ADU adds “gentle density” to communities, says affordable-housing advocate Harold Simon. Photo courtesy of Todd Mason/Halkin Mason Photography

Harold Simon, an affordable-housing advocate and expert who lives in Montclair, recalls trying to get the same ordinance passed in town back in 2011—to no avail. “Montclair, like every other community in New Jersey, has a need for more housing, but it’s an old community,” says Simon. “There are real limits to how much more housing you could put into a place like Montclair. So you could either build apartment buildings, or you could add an ADU.”

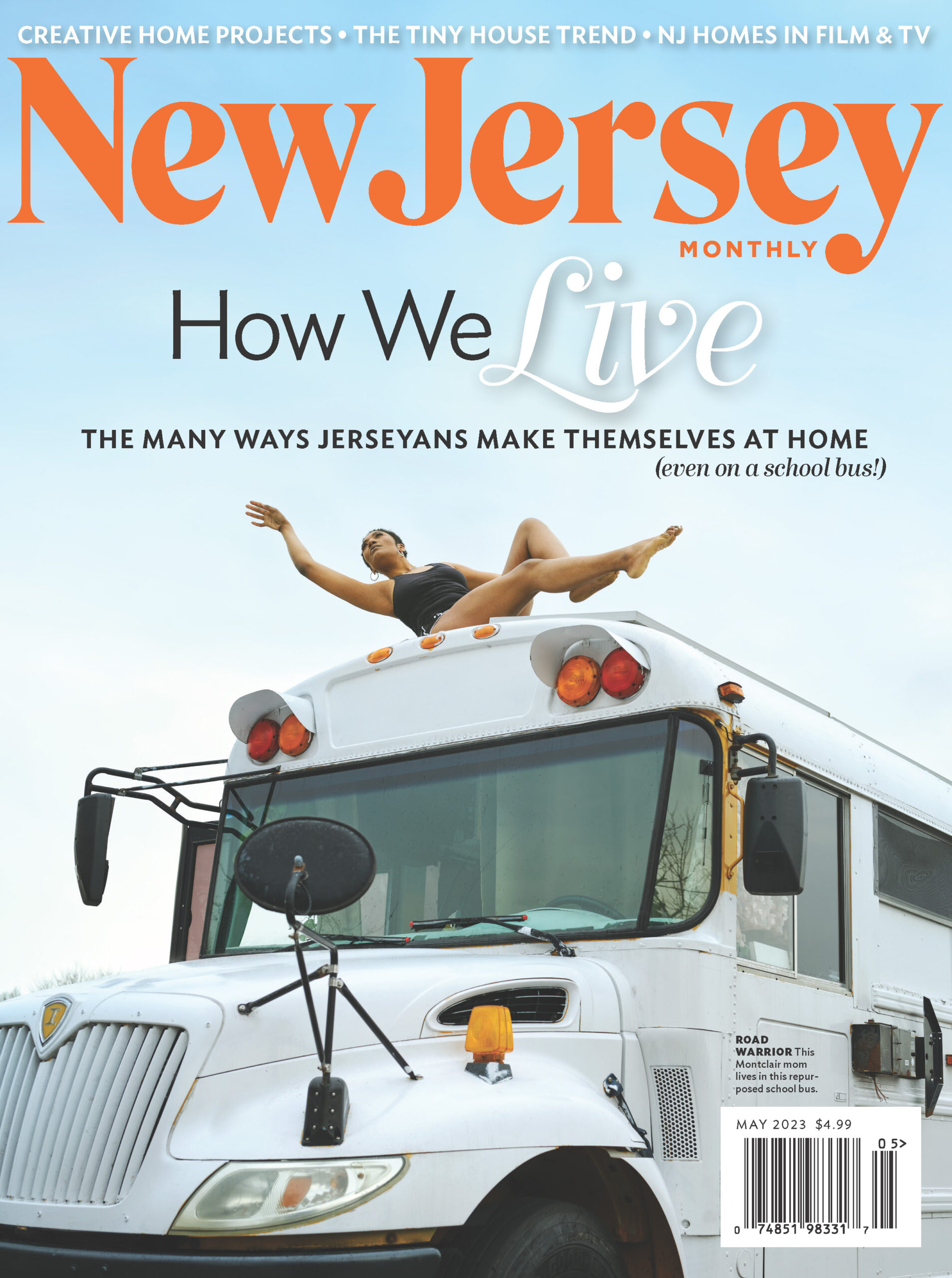

Buy our May 2023 issue here. Cover photo by Chris Buck

ADUs aren’t just for the elderly. The units can be an alternative for any adult looking to rent. And because ADUs are built on already-owned properties, more homes can be added to the market without the need for more space. Many say ADUs are a potential solution to the housing crisis.

“It doesn’t add new infrastructure, for the most part,” adds Simon. “It’s a great way to add housing units to the community without additional cost to the community. The impact is marginal, and it adds gentle density.”

An ADU on a family member’s property can also be a great place for a recent college graduate to live if they can’t afford to pay rent, yet want some independence. Most ADU ordinances also allow for homeowners to rent out the pads for additional income.

Property taxes do increase when an ADU is added to a home, but that’s usually offset by the added value of having rental income or a free place for a relative to live.

Or homeowners can choose to move into the ADU and rent the main house, giving them extra income. Lippel says sometimes homeowners work out deals where their renters shovel snow or do other chores in exchange for a break in rent.

So what’s the next step for ADUs in New Jersey? State legislators are currently working on a bill that would allow homeowners statewide to build units on their properties. The bill, sponsored by state assemblyman Raj Mukherji, could be a step toward making more affordable housing available in the state.

Architect Marina Rubina Rubina aims to “make small places feel large.” Photo courtesy of Todd Mason/Halkin Mason Photography

There is a lot to consider when building an ADU on your property. Marina Rubina, a Princeton-based architect who has been in practice for over 20 years, has designed many ADUs ranging from 400 to 1,200 square feet, and says the tiny home and the main residence must work in unity.

“[I think of] how to make small places feel large and how people can live together on the same property and not be in each other’s way,” says Rubina, who has seen ADUs rise in popularity in recent years. “With ADUs, you get to know the people who are living next to you. It’s more of a friendly relationship than living in a giant apartment complex.”

An ADU must work in unity with the main residence, Rubina says. Photo courtesy of Todd Mason/Halkin Mason Photography

That was true for Montclair couple Joel Patenaude and Judy Hoffstein. When they moved into their home, they were thrilled to realize they could convert the former doctor’s office attached to the back of their house into an apartment for Hoffstein’s aging parents. “It made for a nice lifestyle for them,” Patenaude says. “Initially, they had their independence, and we ate with them a couple of times a week. Then we had all of our meals with them.”

The apartment had a separate entrance, giving his in-laws privacy. The arrangement worked out well for everyone, he says, including his children, who were able to spend quality time with their grandparents. As his in-laws aged, Patenaude and his wife eventually brought in hospice workers. ADUs were legal in Montclair at the time if they were used for elderly parents.

“When my mother-in-law died, I buried my friend,” says Patenaude. “We were able to develop a great relationship; that’s a really nice aspect of this.”

Jacqueline Mroz contributed to this article.

No one knows New Jersey like we do. Sign up for one of our free newsletters here. Want a print magazine mailed to you? Purchase an issue from our online store.