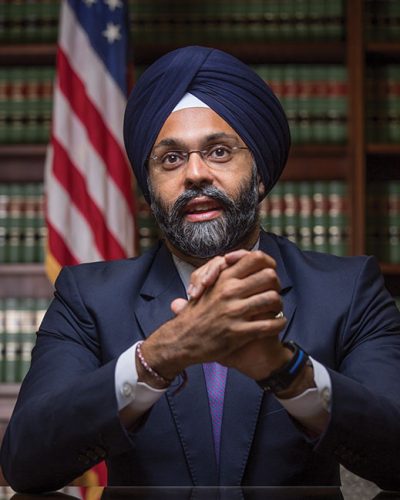

Earlier this year, two radio hosts were suspended for referring to New Jersey attorney general Gurbir Grewal as “turban man.” Grewal, the first Sikh-American in U.S. history to be named a state attorney general, shrugged off the slur.

“For me it was a routine occurrence,” says the 45-year-old Glen Rock resident. “The only difference was that, because it was on the radio, everyone else heard it, too. It was encouraging that so many people called it out.”

Politicians including Cory Booker and Phil Murphy railed online that bigotry has no place in New Jersey. Grewal acknowledged the incident with a tweet: “My name, for the record, is Gurbir Grewal,” he said in part, and quietly moved on.

Usually, the ridicule happens one-on-one. The public nature of the slur by radio personalities Dennis Malloy and Judi Franco, co-hosts of The Dennis & Judi Show on NJ101.5, presented an unwanted opportunity to point out the intolerance to which Grewal has grown accustomed.

“I’ve been called towel head, rag head, turban head, terrorist and every version of the N-word you can imagine,” says Grewal. “I’ve been told to get out of this country, refused service at places of business, and told to take my hat off if I want to come into an establishment.” In a recent incident, the sheriff of Bergen County, Michael Saudino, was heard making offensive comments about Grewal, as well as Lieutenant Governor Sheila Oliver and African-Americans in general. The sheriff subsequently resigned.

None of that has altered the impressive arc of Grewal’s career. A New Jersey native, Grewal earned a Bachelor of Science degree in foreign service from Georgetown University School of Foreign Service, and a law degree from the College of William & Mary Marshall-Wythe School of Law. After starting out in private practice, he served as an assistant U.S. attorney in the Eastern District of New York. From 2010-2016, he worked as an assistant U.S. attorney in the criminal division of the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of New Jersey, where for the latter three years he headed the Economic Crimes Unit, building a reputation for prosecuting white-collar and cybercrimes. A stint as Bergen County prosecutor followed.

Murphy appointed Grewal as the state’s 61st attorney general in January. His priorities make clear his long-standing disdain for social injustice, and his desire to protect the state’s most vulnerable individuals.

They include immigrants, especially DACA recipients, whose right to be in the United States he and 15 other state attorneys general are suing the Trump Administration to uphold; low-level opioid addicts, who he is steering toward treatment centers instead of jail; and anyone without a badge. His 21/21 Community Policing Project, launched in April, mandates that all 21 New Jersey county prosecutors host quarterly meetings in which religious leaders, civil rights groups, school representatives and other members of the public get a chance to mingle with local law enforcement.

The gatherings, required to take place on community turf like church basements or school auditoriums instead of police stations, sound like recipes for unruliness. But Grewal was encouraged when he recently attended the Atlantic City Community Walk that ended with a local woman asking him for a hug—a bonus, considering the more immediate goal of the program, which is promoting stronger relations between police and the communities they are assigned to protect. Grewal feels that’s crucial, given the current climate of political and social discord.

“I don’t know where we went wrong, where we got to this point that led us to people carrying torches and chanting, ‘Jews will not replace us’ on college campuses,” he says, recalling the deadly 2017 Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia. “But there are these chasms of distrust and fear that are preventing law enforcement and community from working together. The thing about those divisions is, I always thought they could be bridges. If there are historical issues, things that happened in the past that are causing distrust, the time to close the divide is before a crisis. You don’t want to be talking to the community for the first time before yellow police tape.”

Grewal recently plunged into yet another kind of fray. Following a grand jury investigation in Pennsylvania that revealed a longtime pattern of sex abuse by priests in that state, Grewal created a task force to investigate similar allegations in New Jersey. “We owe it to the people of New Jersey to find out whether the same thing happened here,” says Grewal. “If it did, we will take action against those responsible.”

In person, Grewal exudes a fierce and serious demeanor befitting his job, which requires him to assure the safety and security of New Jersey’s 9 million citizens. He answers questions with an air of supreme, unswerving confidence. Once he’s made eye contact, he doesn’t let go.

Grewal is serious about personal commitments, too—like keeping his over six-foot frame trim and maintaining the beard and turban that identify him as Sikh. Every day, before being accompanied by a state trooper for the 80-mile commute to Trenton from the home in Glen Rock he shares with his wife and three daughters, he lifts weights at a nearby gym. If he can, he fits in a run.

Amardeep Singh, a mentor to Grewal and the brother of Hoboken Mayor Ravinder Bhalla, would expect nothing less, given the diligence and self-discipline he remembers the attorney general cultivating as a kid in Glen Rock.

“He’s a grinder. He’s a hard worker,” says Singh, a senior program officer at the Open Society Foundations (financier George Soros’s international grant-making network). Bhalla, 44, is New Jersey’s first Sikh mayor and Grewal’s best friend. Singh, who lives in Hoboken next door to his brother, is a few years older. Grewal and Bhalla looked up to Singh because he went to law school and worked in the public interest. That didn’t sit all that well with both sets of their Indian immigrant parents.

“The fields we all entered were novel for our families,” Singh says. “I was the guinea pig for Gurbir and Ravi in that I thought, What can one do with a law degree? The path of being a lawyer to fight for the public interest wasn’t the preferred path of my immigrant parents, who wanted me to make money. But Gurbir and Ravi probably thought, Amar’s doing it, maybe we can do it, too.”

Grewal, an only child, was a self-described “army of one” with a penchant for Law & Order marathons and, according to Singh, making up rap songs with his buddy Bhalla. “One time Gurbir and Ravi and I were at these tennis courts in Fairfield,” he says, “and some other kids were making fun of us for our appearance, and we were giving it back to them, and lo and behold Ravi and Gurbir came up with this rap about having Sikh pride and nowhere to hide.”

Grewal’s parents arrived in the United States from India in the early 1970s; both are naturalized U.S. citizens. His father is trained as an electrical engineer, his mother has a background as a bookkeeper. They are semi-retired, but still live in New Jersey and often see their granddaughters—ages 9, 7 and 5. “The first generation of any immigrant group is just trying to lay down roots,” says Grewal. “The second generation has the luxury to do something different. To start giving back.”

That is in keeping with the values of Sikhism, a monotheistic religion started in the 16th century that claims 27 million followers (2 percent of India, a country of 1 billion, is Sikh). “If you look at Sikhism and distill it to its essence, we believe in selfless service to others. During prayers, we always pray for the well being of all of humanity. To me that fits with being a public servant,” Grewal says.

The public has not always been great about reciprocating. Like most attorneys general, Grewal is often sued over his office’s initiatives by “folks who claim I’m violating the Constitution by limiting their ability to carry guns,” among other issues. “It’s just part of being a public figure,” he says. More troubling is that he, like Bhalla, has been the subject of threats of violence in addition to xenophobic insults. For that reason he prefers not to disclose the names of his family members, including his wife, a neurologist who was born in India.

Still, he is maintaining a firm grip on what he sees as his opportunity to change perceptions, to let it be known that “you don’t have to look a certain way, believe a certain way, or love a certain way to love this country,” he says. When asked about why he became a prosecutor, he tells a story he often revisits in speeches: Just after September 11, 2001, when he was working at one of the biggest law firms in Washington, D.C., a homeless man who regularly lingered outside his office building would shout, on spotting Grewal, “I found him! I caught Bin Laden!”

“It forced me to take different ways in and out of the building, because it was embarrassing when I was with clients,” he says. But it was also embarrassing that no one ever mentioned the abuse, to Grewal or to the man accosting him. “I started to think about how I could change that, and I thought, what better way than to get out there in front of juries, where you could show that even though you look different, you’re doing something intertwined with what it means to love and represent this country.”

The attorney general job magnifies, massively, that drive to be seen as American, not foreign. It also highlights much that’s unique about New Jersey.

“We’re such a welcoming, diverse state with progressive leaders and progressive communities, it’s sort of the perfect storm of factors that allowed this to happen,” he says of his appointment. “When the governor nominated me, it proved that the American dream is alive and well in New Jersey.”

Tammy La Gorce is a frequent contributor to New Jersey Monthly.