St. Clare’s Hospital in Denville occupies a stretch of Pocono Road facing the Rockaway River Country Club and its 18-hole golf course. It’s a pretty setting, and the hospital itself, one of four campuses that make up the St. Clare’s system—Boonton, Dover and Sussex are the others—in some ways has never looked better.

In June, hospital leaders were thrilled to learn that the Denville and Dover facilities had received an A safety rating from the Leapfrog Group, an independent association of employers and other health care purchasers. “That not only places us among the best hospitals in New Jersey, but among the best hospitals nationally,” says president and CEO Leslie Hirsch.

In the last three years, with help from the Colorado-based Catholic Health Initiatives (CHI), and outside funders, the Denville hospital has completed several important capital projects, including a newly updated emergency department and an impressive 24-bed, 48,000-square-foot maternity center. Construction projects have also been completed on other St. Clare campuses.

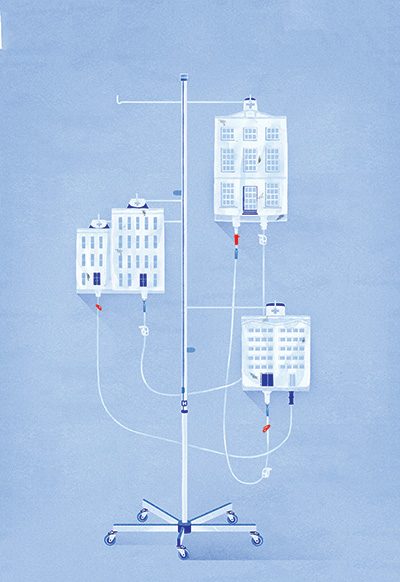

And yet, like many other community hospitals in the state in recent years, St. Clare’s has struggled financially. In March, its board and CHI agreed to sell the system to a suitor with deep pockets: Ascension Health Care Network, a for-profit joint venture between Ascension Health Alliance, the nation’s largest network of nonprofit Catholic hospitals, and a private-equity partner. Ascension Network was created to acquire struggling nonprofits like St. Clare’s and convert them into for-profit businesses.

“Since 2008, and despite our financial problems, CHI has been very generous,” Hirsch says. “But we came to the realization that the marketplace has changed radically, and we needed to form alliances with other hospitals and providers. If CHI couldn’t help us do it”—CHI’s hospitals aren’t clustered in the Northeast—“we had to seek another organization, for-profit or otherwise, that could, and also help us better serve our mission.”

St. Clare’s isn’t the only New Jersey hospital system to be placed on the sales block recently. Financially strapped and facing a radically shifting health care environment, other hospitals have sought a white knight and been acquired. In the Garden State in the last four years:

• Meadowlands Hospital Medical Center in Secaucus was purchased by Newark-based MHA, a private investment company.

• Hoboken University Medical Center and Christ Hospital in Jersey City, both nonprofits, were sold to Hudson Hospital OpCo, a Delaware-based for-profit that also owns Bayonne Medical Center.

• Mountainside Hospital in Montclair was sold by its for-profit owner, Merit Health Systems, to a partnership of Hackensack University Medical Center, a nonprofit, and LHP Hospital Group, a Texas-based for-profit. Mountainside now operates as a for-profit.

• Nonprofit HackensackUMC and its equity partners also won state approval this year to acquire the shuttered Pascack Valley Hospital in Westwood. The state approved the deal over objections from nearby Englewood and Valley hospitals that there isn’t enough medical need in the area to support three hospitals. Now, with an infusion of $35 million from Hackensack and its partners, Pascack Valley, formerly a nonprofit, is being renovated for a spring 2013 reopening as a for-profit.

As another way to stave off insolvency, individual hospitals are merging. In South Jersey, for example, the merger of two nonprofits—South Jersey Healthcare and Underwood-Memorial Hospital—awaits approval from the state Department of Health and Senior Services. Their consolidation, when completed, will create a nonprofit regional network serving Gloucester, Salem and Cumberland counties.

Rather than merge, some hospitals remain independent but agree to share services, programs and medical staff. In June, for instance, just such an agreement was signed between Palisades Medical Center, a small, 202-bed hospital in North Bergen, and HackensackUMC, an area titan. Palisades gets access to Hackensack’s wide array of nationally ranked services and programs, which it could not afford to create on its own. Hackensack broadens its geographical reach.

In short, consolidation, in one form or another, has become the name of the game. Of the state’s 72 acute-care hospitals, 67 percent (about 50 facilities) are now part of a multi-hospital system, according to the New Jersey Hospital Association. Signs are this trend will continue and even accelerate. Meanwhile, small, independent hospitals struggling to find the right suitor or merger partner must fend for themselves, often with dire consequences for their employees and communities. Since 2000, 19 New Jersey hospitals have been forced to close, including Pascack Valley and Christ hospitals. The purchase of Pascack Valley by HackensackUMC and of Christ Hospital by Hudson Hospital OpCo are restoring those two to life. For the others, no such rescue looms.

Consolidation has its critics. Among other things, they argue that for-profit managers too often put a hospital’s bottom line before its community mission. “Our real concerns are that staffing gets cut and services get cut, so that high-profit services stay and lower-profit ones go,” says Jeanne Otersen, director of public policy for Health Professionals and Allied Employees, the state’s largest health care union. Community and advocacy groups have voiced similar concerns, particularly that clinics and other local services might be cut back.

Some academic research supports these claims, though not every conversion from nonprofit to for-profit results in the ditching of lower-profit services like psychiatric emergency and women’s care in favor of big-ticket items like angioplasty and open-heart surgery. “You shouldn’t pre-judge a hospital by its legal status, but by how it acts and treats its community,” says Elizabeth Ryan, president and CEO of the New Jersey Hospital Association. St. Clare’s Hirsch agrees, adding in the case of his own institution: “Our tax status [nonprofit to for-profit] may have changed, but not our mission.”

Several factors are fueling the move toward for-profit status. It is assumed that for-profit managers are more apt to apply no-nonsense, cost-effective strategies to the task of running a hospital or hospital system, thereby increasing efficiency (and profitability). Further, for-profit institutions are likely to have greater access to private capital with which to expand and update their facilities.

Still, as the industry consolidates and the number of nonprofit to for-profit conversions continues to rise, many say the public interest needs to be better protected. Advocacy groups like the New Jersey Appleseed Public Interest Law Center, as well as community groups, health care workers’ unions and others argue that the state should more closely vet the deals beforehand—and more carefully monitor them afterward.

In August, progress toward that goal was halted, at least temporarily, when Governor Chris Christie conditionally vetoed a bill that would have affected for-profit hospitals that are reimbursed by the state for part of the cost of caring for patients who have no health insurance. (According to the Department of Health, those state subsidies totalled $665 million in fiscal 2011.) The bill would have required those hospitals to disclose the same financial and governance information as nonprofits receiving state payments for charity care.

How would changing the disclosure rules help patients? According to Phyllis Salowe-Kaye, executive director of New Jersey Citizen Action, Jersey’s largest citizens’ organization, “If a hospital receiving charity care funds claims financial difficulties as the reason to cut services or staff, or close in-patient units, then our regulatory agencies, elected officials and local communities should be able to accurately weigh the entire financial picture” to judge the merits of those claims. (The bill is expected to be sent back to the governor after the state commissioner of health completes a six-month review of current for-profit reporting requirements.)

In New Jersey—historically a fragmented health care market, with lots of independent community hospitals and small-group physician practices—consolidation has been especially fierce in recent years. “In one sense, New Jersey is a microcosm of what’s going on across the country, but the state is perhaps more interesting because it all happened so fast and all at the same time, especially in the number of for-profits coming in,” says Sarah Vennekotter, an analyst for Moody’s Investor Service, which tracks the financial health of a group of New Jersey nonprofit hospitals.

Across the country, health care spending by individuals, insurance companies, states and the federal government constitutes about 17.9 percent of GDP (the value of all domestically produced goods and services), and is expected to increase to 20 percent of GDP, or $4.6 trillion, by 2021, according to government projections.

As it happens, the biggest chunk of the overall health care dollar goes to hospitals, which is why states, employers, private payers and certainly Washington have been collectively pushing the industry to more aggressively rein in costs.

The Affordable Care Act (Obamacare, a name Obama himself claims he now likes) cuts federal funding, resulting in a drop in Medicare payments to New Jersey hospitals of about $4.5 billion over 10 years, according to the New Jersey Hospital Association. To make up for this cut, hospitals will be forced to become more efficient, delivering high-quality care at lower cost.

There is also a carrot: broader coverage of residents who would otherwise show up at the state’s emergency rooms with no insurance, thereby burdening hospitals that under state law can’t turn them away. (Only part of the cost of treating such patients is reimbursed by the state. The rest is the hospital’s responsibility.) True, the ACA doesn’t cover undocumented immigrants; nor, after last June’s Supreme Court ruling, does it require all states to expand their Medicaid programs, as it originally did. (Governor Christie has said he doubts the state’s program could be expanded significantly.) These reform gaps—along with cuts in federal charity care—will certainly reduce the benefits hospitals in poorer parts of the state will see from the ACA. Still, beginning in 2014, the number of uninsured in the state is expected to drop by 41 percent, from 1.1 million to about 650,000, according to the Center for State Health Policy at Rutgers.

Architects of reform are also trying to wean hospitals and other providers from their traditional forms of reimbursement. Instead of paying providers for services performed, the new ideal is to pay for improved results (a.k.a. improved patient outcomes), using the best available clinical and research evidence to guide decision making. To put this new model into practice for Medicare patients, the ACA created what are called Accountable Care Organizations (see “A Positive Approach to Senior Health,”). Private payers have also created programs to promote these goals.

Hospitals have responded by changing their business model, something industry leaders say they would have done even without the kick in the pants from Washington. Whatever the case, the new model calls for greater coordination of care—a now-ubiquitous buzzphrase that basically means better communication and cooperation among providers on a given case. The aim is safer, more efficient care, in theory leading to shorter hospital stays and fewer readmissions (due to relapses, complications and the like). That goal goes hand in hand with widening access to primary and preventive care to keep people out of hospitals in the first place.

It all sounds reasonable, but for hospitals—especially small hospitals—there is a catch. If people with chronic diseases like diabetes and heart disease can be treated at home, in community clinics or in other outpatient settings, they don’t need to be admitted to hospitals. That cuts overall costs, because inpatient care is always more expensive than outpatient care. But it also reduces hospital revenues. “Many hospitals are trying to change their business model,” says state Health and Senior Services commissioner Mary E. O’Dowd, “but it doesn’t come without growing pains.”

The goal of coordinating care involves another kind of growing pain—a technological one. “One part of the cultural change involves the use of computers, not only to collect data and move it around quickly, but to standardize care using evidence-based medicine,” says Dr. Richard Goldstein, former New Jersey commissioner of health during the Kean administration. That requires a sizeable investment in information technology, one that smaller hospitals and one- and two-doctor physician practices often can’t afford (see “Solo Practitioners,”).

Smaller facilities can be forgiven if they view the deck as stacked against them. It is much easier (and more cost-efficient) to share information within an integrated system that offers a full range of services, or within a multi-specialty group practice, than it is for a small hospital or practice that has to forge connections with outside entities.

The move to reimburse for results rather than for services performed also places a greater burden on smaller institutions. Consolidation throws smaller hospitals a lifeline, injecting the capital they need to compete, stay solvent and continue to serve their communities. At the same time, it enables larger systems like HackensackUMC—which had $1.2 billion in net patient-service revenue last year and in mid-August received an A-minus credit rating and positive outlook from Standard & Poor’s—to extend their reach, care for more patients, and perhaps keep New Jerseyans from decamping to New York City or Philadelphia when they need highly specialized, state-of-the-art care.

By strengthening hospitals financially, consolidation helps them withstand the growing competition from independent ambulatory care facilities, especially surgi-centers, which don’t have to take patients who lack insurance and can’t afford to pay.

In practice, consolidations, like births, can go smoothly or result in major pangs and complications. Two recent examples illustrate the point. Mountainside Hospital’s path from red ink to black, under first one and then another new owner, has won almost universal praise. On the other hand, Hudson Hospital OpCo’s purchase of Christ Hospital has been mired in controversy almost from the day it was announced.

In a Sopranos episode in 2007, Mountainside got a mild publicity bump when Tony’s son A.J. was put in the psychiatric ward there after trying to drown himself in the family swimming pool.

In fact, the life in peril was not the fictitious teen’s but the hospital’s own. The 365-bed, nonprofit facility in Montclair was reportedly losing $1 million a month, had an anemic occupancy rate and a vocally restive staff. That same year, Merit Health Systems, a for-profit hospital management company based in Louisville, Kentucky, offered to buy Mountainside from Atlantic Health System—the parent company of Morristown Medical Center and three other New Jersey hospitals—for $30 million, a sum that community and advocacy groups objected to as grossly inadequate. To that point, very few for-profit takeovers of nonprofit hospitals had even been proposed in New Jersey, and the state had approved only one. Mountainside became the second.

Many Mountainside doctors had felt bullied and unappreciated under Atlantic Health. The new leadership recognized the need to win the medical staff’s trust and “change the culture of the hospital,” says John Fromhold, a Merit official who became Mountainside’s president and CEO in October 2008. Among other things, he says, the team took steps to deliver the results of lab and other tests to doctors “in a more timely manner,” enabling them to begin treatment faster. To streamline admitting and discharging, case-management nurses were posted in the emergency room seven days a week until 11 pm.

Doctors agreed to work with management to reduce the number of tests and other clinical orders that benchmark data showed were unnecessary and that were swelling costs. “There was a lot of fat trimming when Merit took over,” says Dr. Konstantin Walmsley, president of the medical staff, “but the administration also impressed upon the medical staff how important [the cutting] was.”

Gradually, Mountainside’s average length of stay for Medicare patients decreased by a full day. At the same time, readmissions dropped below state and national averages, evidence that shorter average stays were not harming those patients. “This tells me we’re not rushing patients out the door, not discharging them too quickly,” says Fromhold. The impact on the hospital’s balance sheet has been equally salutary, moving it from deep in the red to solidly in the black. “In 2010, we had the second strongest operating margin [among hospitals] in the state,” Fromhold says. “Last year, we were number one [in operating profit], and thus far this year we are also number one, and this from a hospital that five years ago was ready to be closed.”

“Merit leadership succeeded in making Mountainside a much more efficient facility without apparently jeopardizing quality,” says Elizabeth Litten, a health attorney and partner at Fox Rothschild, a Princeton law firm. “That emphasis on operational efficiency”—as opposed to simply raising prices—“is a very helpful perspective.”

Despite the turnaround, in 2010 Merit was forced to sell the hospital (for $190 million) when its private-equity partners decided to cash out their investment. “I applaud John Fromhold and his team for doing a tremendous job of not only making the hospital more efficient but enhancing the quality of the programs,” says Robert Garrett, president and CEO of HackensackUMC, which now owns a 20 percent stake in the renamed HackensackUMC Mountainside. “We are going to continue that tradition, so that the community will be even more proud [of its hospital] than it is today.”

In Jersey City, few are celebrating what’s happened with Christ Hospital. Early last year, local hackles were raised after the Christ Hospital board accepted a bid for the bankrupt facility from a California-based nonprofit that some activists and public-interest groups charged had a record of providing shoddy services. That bidder withdrew, replaced this year by another suitor, Hudson Hospital OpCo (HHO).

Activists noted that after HHO acquired Bayonne Medical Center and Hoboken University Medical Center, it cancelled most of their managed-care contracts with insurance companies. That meant it was no longer in network with those plans, so patients in those plans who did not have out-of-network benefits would have to pay more, potentially putting certain procedures out of their reach.

In a move that caused insurers to join the chorus of protest, the Bayonne and Hoboken hospitals began to admit patients through their emergency rooms, even if their cases were not true emergencies. That tactic had the effect of squeezing the insurance plans. Under state law, when patients who lack out-of-network benefits are admitted through an emergency room, the plan rather than the individual is obligated to pay the difference between in-network and out-of-network charges. Opponents, warning that HHO would do the same thing if it were allowed to acquire Christ Hospital, even backed another bid for the hospital.

Nonetheless, in late March, the United States Bankruptcy Court of New Jersey approved the takeover.

The protests did not entirely fall on deaf ears. In its own subsequent approval letter to HHO, the state Department of Health and Senior Services (DHSS) set 23 conditions for the transfer of ownership, including “reasonable efforts to renegotiate the current HMO and commercial insurance contracts of Christ Hospital.” If those efforts failed, HHO was ordered to notify both DHSS and the Department of Banking and Insurance. “It was important to have put these conditions in to ensure continuity of services and transparency,” says Commissioner O’Dowd. “Earlier transfers of ownership didn’t have such aggressive conditions.”

Yet the state stopped short of prohibiting an out-of-network model. For one thing, says O’Dowd, “these are independent negotiations between two businesses—a health care institution and a payer—and it’s a delicate thing for the state to get involved.” Furthermore, she notes, the problem is not limited to one or two hospitals or to for-profits only. “Many hospitals across the state, including almost all nonprofits, have gone out of network with at least one or two of their payers.” In sum, she says, it’s hard to justify imposing requirements “that are more aggressive than for any other hospital in the state.”

At the end of June, HHO severed Christ Hospital’s contracts with 19 of its commercial health plans and two of its four privately managed Medicaid plans. (Christ Hospital did not respond to multiple requests for an interview.) Only the remaining Medicaid plans and a private Medicare plan continued to be in network. Yet, in doing exactly what activists warned it would, HHO did not violate any rules. It properly notified officials of its intentions and waited the requisite 30 days.

In an HHO statement reported on nj.com, the company defended its actions, saying it would prefer to pursue an in-network business model, but only with health plans that “provide equitable rates of reimbursement that support the provision of high-quality care.” Since then, it has apparently found some. Currently it is in-network with seven carriers, including five Medicaid plans, according to its website.

Controversy isn’t inevitable when hospitals combine. In South Jersey—which has fewer hospitals than the North and often loses patients needing highly advanced care to Philadelphia—one of the most potentially significant mergers in the state is proceeding smoothly toward completion. The two nonprofits—South Jersey Healthcare in Vineland (Cumberland County) and Underwood-Memorial Hospital in Woodbury (Gloucester)—have won approval from the Federal Trade Commission, whose Bureau of Competition is responsible for approving hospital mergers. State approval is expected by the end of the year.

When combined, the two hospitals will be able to create one instant-access database, making it easier to coordinate and speed patient care. All the services, specialists and technologies the two hospitals had individually will be available to all patients whom the combined hospitals treat. The hospitals will be able to broaden their community services and clinics, making access to care easier for South Jersey residents.

Also in the works at press time is an affiliation agreement between University Hospital, Newark, a teaching hospital, and nonprofit Barnabas Health, the state’s largest health care delivery system and its second biggest private employer, headquartered in Livingston. The negotiations are one outcome of the complex restructuring of the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, which will merge most of its schools with Rutgers University, forming the Rutgers School of BioMedical and Health Sciences. Even before the legislation authorizing the restructuring became law, news reports referred to Barnabas as a “leading contender” to manage the day-to-day operations of University Hospital, which is part of UMDNJ. Barnabas president and CEO Barry H. Ostrowsky said this summer that the fit would be a good one: “We have a major commitment to the city of Newark through Beth Israel Medical Center”—part of the Barnabas system—“and urban health care…is important to us. We also have a strong commitment to graduate medical-school education, with three major teaching institutions in our system.”

Mergers, acquisitions, management contracts, clinical agreements—all are reshaping the landscape of health care, along with concepts like evidence-based medicine and coordinated care. The stated aim is greater efficiency and better care. Sometimes it’s simply business survival. Yet, as is often said, health care is not like any other business. “It’s more complicated in the health care world because there’s a mission,” says Ostrowsky. The question, he says, is whether hospitals, for-profit or nonprofit, will be able to thrive as businesses without compromising that mission.

Wayne J. Guglielmo is a frequent contributor to New Jersey Monthly.

Click here to read more Top Doctors stories.