The room has all the amenities you’d expect at a good hotel: freshly laundered blanket tucked into the sides of a queen-sized bed, dark wood headboard, reading lamp, leather armchair, flat-screen television, private bathroom.

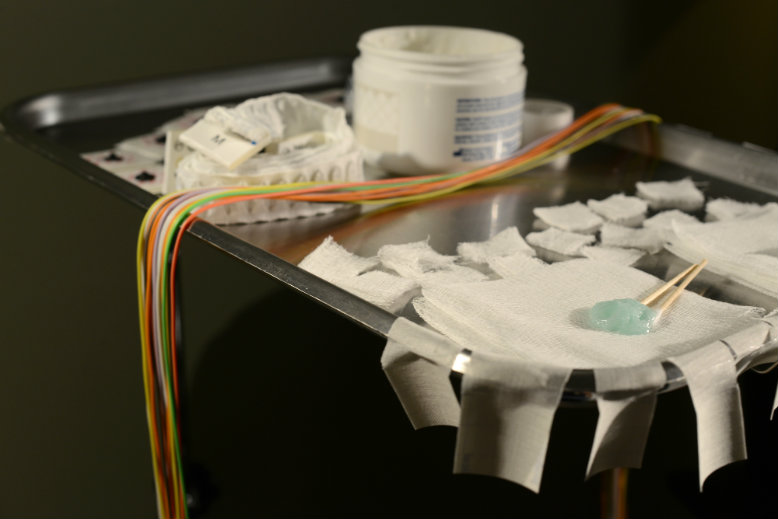

But on the bedside table, there’s a machine with a tube snaking out its side. On the wall alongside the television, video cameras are trained on the bed. And then there’s the stainless-steel tray table of disinfecting wipes, cotton swabs, lengths of tape and gauze, dabs of adhesive goop and a collection of long, multi-colored wires.

Welcome to the sleep lab at Saint Barnabas Sleep Center at Madison. Jack Li is here tonight for his second sleep study with help from Kerry Kelley, the lead sleep technician at the lab. Kelley engages Li in gentle conversation. They talk about the national parks both have visited and the intricacies of Li’s job as a systems engineer at Picatinny Arsenal.

While they talk, Kelley adheres the wires to different parts of Li’s body: six on his scalp to measure brain waves (EEG); two on his jawline and four on his legs to measure muscle movement (EMG); two next to his eyes to measure eye movement (EOG); and two on his torso to track cardiac activity (ECG). She attaches a microphone to his throat to detect vibrations from snoring and a pulse oximeter to one of his fingertips to measure oxygen levels. Next, Kelley wraps two adjustable belts around Li’s chest and stomach to measure respiration. Finally, she covers his nostrils with a breathing apparatus that delivers continuous positive airway pressure, or CPAP.

Now, good night and sweet dreams.

Photo by Jennifer Altman

Much about sleep remains a mystery. Before 1953, when Eugene Aserinsky, a graduate student at the University of Chicago, discovered rapid eye movement—a sleep stage during which the eyes dart wildly under the eyelids—sleep was a relative blind spot in the scientific literature. Dreams were left to psychoanalysts to interpret and artists to mine for inspiration. Over the past three decades, science has unearthed a flood of information about what happens in the body and mind as we sleep.

Li underwent his first sleep study in 2006 at CentraState Medical Center in Freehold after complaints from his family about his loud snoring. As a result, he was diagnosed with obstructive sleep apnea, or OSA, a disorder that causes sufferers to repeatedly stop breathing throughout the night. The apneas are marked by a violent snort or choking sound. During his test, Li stopped breathing 70 times in one hour, or more than once a minute.

READ MORE: “Sleep Apnea: Causes and Cures”

The doctor at CentraState recommended Li use CPAP. Li didn’t know much about CPAP, but the idea of wearing a mask every night was unsettling. “I told them I wasn’t really comfortable wearing something while I slept,” he says. “So I asked for other alternatives.” The doctor suggested a better diet and exercise, and Li went on his way.

Almost a decade later, the 46-year-old Mount Olive resident rarely has a refreshing night’s sleep. He drinks three or four cups of coffee a day and sometimes sleeps 10 hours or more on weekend nights. And no, he hasn’t followed the suggestions for a healthier diet and exercise. “I guess I’m just lazy,” he says with a laugh during a phone interview the day before his sleep study.

Dr. Marc Benton, medical director at the Saint Barnabas Sleep Center at Madison (and one of NJM’s 2015 Jersey Choice Top Doctors), is overseeing his case. The week prior to Li’s sleep study, Benton ordered a preliminary home test. The test showed that Li had gotten worse over the years: now he stopped breathing 93 times an hour. “Dr. Benton thinks I should be dead,” says Li, acknowledging the severity of his case. But Li is not all that unusual.

“In the U.S., the incidence of clinically significant sleep apnea in men is probably 24 to 28 percent,” says Benton. “Which, when you get right down to it, is a monstrous number. With women, it’s probably 10 percent.”

According to the International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD-3), sleep apnea is one of roughly 80 sleep disorders. Other common sleep disorders include insomnia, defined as difficulty falling asleep and/or staying asleep, and restless leg syndrome, an overwhelming urge to kick and move the legs while lying or sitting.

READ MORE: Learn about other sleep disorders in “Understanding Sleep Problems”

People with an untreated sleep disorder like insomnia or sleep apnea can accumulate years of sleep debt, functioning as lesser versions of their healthy selves. They become irritable and unable to learn new skills or recall information as easily as their well-rested counterparts. “I used to have a very good memory,” Li says. “I used to be able to remember my credit card number, expiration date, all that stuff. I just can’t do that now.” (The Center for Molecular and Behavioral Neuroscience at Rutgers-Newark is researching the impact of sleep on memory and mood as part of the Rutgers Memory Disorders Project.)

Prolonged sleep deprivation can also cause depression—and not just from irritability and frustration over not sleeping. Matt Walker, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley and consultant for the Rutgers Memory Disorders Project, contends that a sleep-deprived brain remembers negative experiences more readily than positive experiences. In a 2008 article titled “Cognitive Consequences of Sleep and Sleep Loss” (Elsevier Journal of Sleep Medicine) he wrote that sleep-deprived individuals “suffer a negative remembering bias, despite experiencing equally positive-and negative-reinforcing past events.” According to Walker, this might explain “the higher incidence of depression in populations experiencing impairments in sleep.”

Further, clinical evidence indicates that some form of sleep disruption is present in almost all psychiatric disorders. It’s often unclear, however, which comes first, the sleep disorder or the psychiatric symptoms.

Kerry Kelley, the lab manager at the Madison sleep lab, answers Jack Li’s questions about using CPAP comfortably. Photo by Jennifer Altman

Poor sleep leading to poor mental performance isn’t an issue just for adults. Teachers and parents of young students who fall asleep in class or have trouble completing assignments often attribute the behavior to learning disabilities like attention deficit disorder (ADD) or its disruptive sibling, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). But the problem may be as simple as lack of sleep. The American Sleep Apnea Foundation cites studies suggesting that as many as 25 percent of children diagnosed with ADHD may actually have OSA, frequently due to enlarged tonsils.

For children with OSA who are misdiagnosed with ADHD, stimulant medications like Adderall will exacerbate their sleep problems. Photo via Flickr/hipsxxhearts

“Having 5 or 7 or 10 apneas per hour, or interruptions of sleep per hour, is considered well within the range of normal [for adults]. For kids, that is clearly abnormal,” says Benton. What’s more, “they don’t tolerate it as well,” particularly because children require more sleep than adults. Attention-deficit symptoms tend to dramatically decrease after shaving the tonsils, removing them altogether, or removing adenoids, small glands in the back of the throat that fight infection—all procedures that also help relieve sleep apnea in children.

Maria Dimi, the administrative director of respiratory care and neurodiagnostic services at Saint Barnabas Medical Center in Livingston, attends local PTA meetings and teacher conferences to raise awareness about these issues. “We tell these teachers, first of all, you don’t have a degree to label [your students]. Teachers are very quick to say, ‘the kid’s got ADD,’” Dimi says. “Well, it may be because they just aren’t sleeping at night and can’t stay focused during the day.” Unfortunately, ADD medications are also stimulants, which can exacerbate sleep problems.

Dimi has personal knowledge of how a misdiagnosis can affect a young person. Her stepson was diagnosed with ADD at a young age and subsequently was prescribed Ritalin. But when he moved from his mother’s house to Dimi’s home in his sophomore year of high school, Dimi realized the boy’s attention span wasn’t the problem. “We found out that he really had dyslexia and [periodic leg movement], a very mild neurologically based sleep disorder, that was easily treated with medication,” she says. “We went from a kid who was failing and could barely read at a fifth-grade level” to a solid student with an A- or B average.

Hunterdon Pulmonary and Sleep Associates provides a full range of Pulmonary and Sleep services for the diagnosis and treatment of lung disorders, respiratory diseases and sleep disorders.You can call them at : (908) 237-1560

Or simply follow the link below

http://hunterdonpulmonaryandsleep.com/

http://hunterdonpulmonaryandsleep.com/our-physicians/

http://hunterdonpulmonaryandsleep.com/specialties/

http://hunterdonpulmonaryandsleep.com/disorders/

Hunterdon Pulmonary and Sleep Associates provides a full range of Pulmonary and Sleep services for the diagnosis and treatment of lung disorders, respiratory diseases and sleep disorders.You can call them at : (908) 237-1560

Or simply follow the link below

http://hunterdonpulmonaryandsleep.com/

http://hunterdonpulmonaryandsleep.com/our-physicians/

http://hunterdonpulmonaryandsleep.com/specialties/