The closing of Muhlenberg Regional Medical Center in Plainfield hit Vera Harrell with a double whammy. After 29 years working in the laundry and linen department at Muhlenberg, she was laid off from her non-union job with only twelve weeks of severance pay. And about a week after the 355-bed hospital closed on August 13, her aunt had a heart attack in Plainfield. With the town’s rescue squad stretched thin by the need to rush local residents to hospitals scattered over three counties, a full hour passed before an ambulance picked up Harrell’s aunt, she says.

“After the EMTs finally got my aunt into the ambulance, they had to stop and revive her at Plainfield High School on Park Avenue. They passed Muhlenberg, but it was closed. Then they had to stop in South Plainfield at the A&P to revive her again. She could have died.” Finally, the EMTs got Harrell’s aunt to JFK Medical Center in Edison, five miles from Muhlenberg, where she stayed in the ER for two days before getting a room.

Muhlenberg is the eighteenth hospital to close in New Jersey since 2000. Parent company Solaris Health System, which also owns JFK and several rehabilitation and nursing facilities in central New Jersey, claimed it could not sustain the financial losses from operating Muhlenberg. In July, despite community opposition, the state’s Department of Health and Senior Services approved Solaris’s application to shutter the 131-year-old facility.

Plainfield community activists—including area doctors and politicians—continue to fight to restore Muhlenberg as an acute-care medical center. Several doctors and nurses formerly affiliated with Muhlenberg say Solaris’s policies doomed the hospital. A Solaris spokesman denies their claims.

Some physicians worry that the hospital’s closing will endanger their patients’ lives, especially those who require fast access to emergency care. “People with acute problems such as strokes and heart attacks are put at risk,” says Raymond Snyder, a Plainfield family physician who was on Muhlenberg’s staff for 45 years.

Indeed, the Plainfield Rescue Squad is seeing slower response times to emergencies, according to business manager Jenny Pernell. It can now take 25 minutes for the service’s sole ambulance—or another rescue squad’s ambulance—to answer a call, she says, and an hour’s wait is not unusual if they are on another call because of the longer distances to other area hospitals. Squads from neighboring towns help when they can, but they are also under increased stress because of Muhlenberg’s closing, she says.

But Solaris spokesman Steven Weiss says, “To date, we have received no complaints or problems in regard to transferring patients safely and effectively to neighboring hospitals.”

Muhlenberg, a teaching facility with a nursing school and medical residency programs, was Plainfield’s biggest employer. About half of its 1,100 employees were laid off—and many lack the skills or the transportation to get new jobs, sources say. None of the employees was a union member.

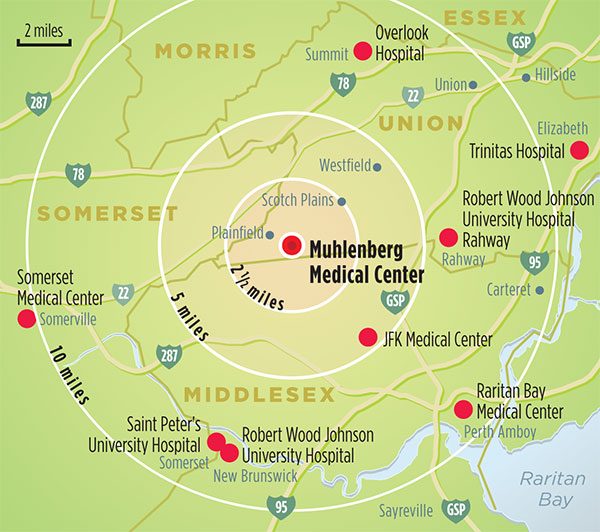

Muhlenberg served fifteen towns in Union, Middlesex, and Somerset counties. That’s one reason why some observers say its passing is having a much bigger impact than the demise of other New Jersey hospitals that have closed in recent years. The distances from Muhlenberg to the eight other hospitals serving parts of the same area range from five miles to JFK to thirteen miles to Trinitas Hospital in Elizabeth and Somerset Medical Center in Somerville.

For the many Plainfield residents without cars, it is difficult to get to these hospitals. Public transportation is inadequate and taxi fare is expensive. While Solaris is supplying a free shuttle bus from the Muhlenberg campus to JFK—required by the state as a condition of closing Muhlenberg—it runs only part of the day and, some residents say, not on weekends. According to Weiss, the shuttle runs seven days a week, from noon until 8:30 pm.

Like every physician and patient interviewed for this article, Snyder says that Muhlenberg was an excellent hospital. Cardiologist Saleem Husain says it had the best outcomes for angioplasty, heart attack, and pneumonia of any hospital in the state. Patient satisfaction with the hospital was also high, doctors and others say.

“The hospital provided very good care—it was very personal and very high-quality care,” says Thomas Reedy, executive director of the United Family & Children’s Society, a social services agency in Plainfield. Reedy, who also worked in Muhlenberg for 32 years, including 20 years in the psychiatric unit, says that surveys by health-care consultancy Press Ganey gave the hospital high ratings for patient satisfaction.

Mary Williams, a teacher at Scotch Plains-Fanwood High School, can attest to that. She says Muhlenberg literally saved her life when she was brought there in a diabetic coma.

Considering how important Muhlenberg was to the region, why did it close? In a July 29, 2008, letter granting Solaris’s application to shutter the hospital, Heather Howard, commissioner of the New Jersey Department of Health and Senior Services, cited continuing financial losses that totaled $16.5 million in 2007 and were expected to hit $18 million this year. She wrote that these deficits imperiled the financial stability of both Muhlenberg and JFK. And she concluded that the surrounding hospitals had sufficient capacity to absorb Muhlenberg’s patients.

In an interview with New Jersey Monthly, Howard said that closing Muhlenberg was a “difficult decision.” But, she said, if Muhlenberg had not been shut down, the state “could have faced a bankruptcy and the unplanned closure of a hospital.” Through an orderly shut down, Howard was able to impose on Solaris “an unprecedented number of conditions” intended to serve the health care needs of the community and the job placement and training needs of employees.

Community activists, however, question whether Solaris was actually losing as much money as it claimed. They note that Solaris was never required to do a needs assessment to determine whether other hospitals could actually replace Muhlenberg’s services. And they contend that Solaris deliberately sold or transferred moneymaking units from Muhlenberg, thereby hastening its demise.

Weiss denies that Solaris did anything to hurt the hospital. In fact, he says, it invested $50 million in equipment and new programs at the hospital. One factor that did Muhlenberg in, he says, is that it was simply no longer economically viable. The hospital had an above-average percentage of its patients who were uninsured or on Medicaid. The state health planning board found that charity care and Medicaid patients accounted for 18.2 percent of Muhlenberg’s volume in 2006, well above the norm for suburban hospitals in the region. For example, the proportion is 7.8 percent at JFK and 4.9 percent at Overlook Hospital in Summit.

Many other hospitals, especially those in urban areas, have this problem, says Betsy Ryan, president of the New Jersey Hospital Association. In her view, the state has underfunded charity-care reimbursement, despite its unusual requirement that hospitals admit all comers. (New Jersey will spend $716 million on charity-care reimbursement this year, about half of the cost of providing care to indigent patients. Those funds will be cut by $111 million in 2009, according to the NJHA.)

Noting that New Jersey pays Medicaid providers less than most other states do, Ryan declares, “If you get underpaid for every Medicaid and charity patient you treat, you can’t sustain operations if you see a large amount of those patients.” This is a prime reason, she says, for many of the New Jersey hospital closings.

Even if Muhlenberg fell victim to market forces and the state’s underfunding of charity care, serious questions have been raised about Solaris’s stewardship since Muhlenberg merged with JFK in 1997 and the Solaris Corporation was formed.

Right after Solaris took over, the company transferred some of Muhlenberg’s lab services to JFK, says Robert Lauer, a South Plainfield cardiologist. Then it replaced the radiology and emergency-medicine groups that were contracted to Muhlenberg with radiologists and ER physicians of its own choice, Lauer says. Insured patients were encouraged to have their tests and elective procedures done at JFK, he says, while the uninsured remained at Muhlenberg.

Karen Gielen, a nurse and Scotch Plains resident who worked at Muhlenberg for 28 years, confirms this account. When she herself needed an MRI, she says, the hospital staff proceeded to schedule it at JFK—a typical practice unless the individual requested otherwise—although Muhlenberg had its own MRI unit.

Solaris also tried to get the hospital’s biggest income generators, including physicians in neurology, orthopedic, vascular surgery, colorectal surgery, and cardiology groups, to admit patients to JFK, Lauer says. However, he and his colleagues resisted these overtures. “We sent most of our patients to Muhlenberg, because we felt they could get better care there.”

Along the way, Solaris sold Muhlenberg’s dialysis unit and cardiac catheterization labs to national chains. Also, while JFK had no elective angioplasty program and Muhlenberg had one of the best in the state, cardiologists based at JFK consistently sent patients to other hospitals for that procedure, Lauer says. If those doctors had done their angioplasties at Muhlenberg instead, he says, those operations alone would have brought in an extra $6 million to $9 million a year. He adds that, though JFK’s cardiologists argued that Muhlenberg did not have surgical backup for angioplasties, neither does JFK, which has now taken over the program.

Weiss denies that Solaris transferred any programs from Muhlenberg in the years before its closing, except for a pediatric department that he says was underutilized. He does acknowledge that the hospital sold the dialysis unit and cath labs, and some programs were consolidated. While expensive tests like MRI scans were centrally scheduled at JFK, he says, patients were encouraged to get them at Muhlenberg if they wanted a shorter wait. As for the referrals of patients for angioplasties, he notes that physicians are free to send patients wherever they and the patients want to go.

As a condition of closing Muhlenberg, Solaris is required by the state to maintain a number of outpatient services on the hospital’s campus for five years, including lab and radiology services; home care; sleep labs; wound treatment, dialysis, and diabetes care units; mobile ICU trucks; and those free shuttles to JFK. There is also a satellite emergency department—a scaled-down version of Muhlenberg’s old ER—that is supposed to handle acute problems such as burns, broken bones, and respiratory issues, says Weiss. “If it’s a life-and-death situation, the EMTs won’t take you there. They’ll take you to a more convenient, full-service emergency department.”

Activists and residents call this satellite unit a “Band-Aid ER” and say that it is too far to hospitals with full emergency departments. While JFK is fairly close, its ER is usually packed. Gielen, who also worked as a nurse at JFK for four years before she retired recently, says that some believe that the ER goes “on divert”—turning away ambulances—quite often, although Weiss denies that. Pernell of the rescue squad says that JFK diverts patients much less often than it used to.

Some in the Plainfield community believe that charity patients are being forced to go to Trinitas. It is true that many expectant mothers and people with urgent behavioral issues are being sent there—and that many of these maternity and psychiatric patients are low-income people who lack private insurance. But that is not the reason they are being referred to Trinitas. Only low-risk maternity patients who have received prenatal care at Neighborhood Health Services (NHS), Plainfield’s federally aided community clinic, are required to go to Trinitas—and that’s because the Elizabeth hospital, alone among the area’s hospitals, agreed to let NHS’s midwives deliver babies there. As for mentally ill patients who are deemed dangerous to themselves or others, they are being sent to Trinitas because its psychiatric unit has the capacity to take them.

Meanwhile, Muhlenberg’s closing has left a vacuum for primary care, which many local residents used to seek in the hospital’s ER. NHS is already seeing an influx of these patients and is planning to hire additional physicians. The clinic is talking with Solaris about placing a satellite on the Muhlenberg campus, says Rudine Smith, the community health center’s president and CEO. Also, she notes, JFK is expecting to get “a lot of unassigned patients who they’re going to direct here. So those patients can have a new medical home, and we’ll continue to refer back to JFK for diagnostic services and inpatient care.” (Unassigned patients are those without primary-care physicians and, in many cases, no health insurance.)

Weiss says that physicians can decide whether to refer their patients to NHS, and he rejects activists’ suggestions that JFK is avoiding charity patients. He emphasizes that JFK will assess and treat all of the patients who come to its ER, as required by law. And he points out that JFK is looking to expand its ER to handle an expected 22 percent increase in the number of patients arriving there.

The community has not given up on Muhlenberg. Hundreds of people showed up at the state planning board hearings on the hospital’s closing and at demonstrations in Plainfield and Trenton. The day the hospital closed, protestors carried coffins through the streets from Muhlenberg to JFK. These people are not going away quietly, and they have strong advocates in State Assemblyman Jerry Green and Plainfield Mayor Sharon Robinson-Briggs. In fact, Robinson-Briggs and the city of Plainfield recently sued the state in an effort to force it to reopen the hospital.

Although Muhlenberg has been up for sale since November 2007, its defenders maintain that Solaris is not really interested in selling it as an acute-care hospital, because that would create new competition for JFK. Weiss insists that no viable offers have been made. Green blames this on Solaris’s refusal to open its financial books. But Weiss says that Solaris will not do that unless a potential buyer has the financial backing and the track record to make a serious bid. To date, none of the bidders has been credible, he says.

Nevertheless, hope lives on in Plainfield. “Muhlenberg hasn’t stopped fighting yet,” says Gielen. “We will continue, and we’ll use every effort to do this legally to restore our hospital. We really need an acute care hospital, because we’re talking about people’s lives, whether or not they have money or insurance. Professionals need to run health care. It should not be run by a business model.”

Ken Terry, a former editor of Medical Economics magazine, is the author of the book Rx For Health Care Reform.

Health Insurance shut down Muhlenberg, just as it shut down the hospital of my birth, through the commercialization of medicine and a leveraging, Ponzi scheme perpetrated on physician, hospital and patient alike. Health insurance must be abolished and Municipal Medical Departments, providing medical care free to the patients and medical schooling free to the student, must be immediately established.

Plainfield should be able to seize the Muhlenberg facilities by eminent domain, under federal authority and with federal compensation, and make them the basis of its Municipal Medical Department. The staff would be hired, as with all MMDs, under federal civil service standards and paid as federal civil servants working in a municipal branch of the federal government.