It was supposed to be a red-carpet moment. The 40 students who had won, via lottery, a spot in New Brunswick’s new technology high school were to pick up their personalized laptops, ogle the tiny robots in the engineering classroom, soak up high expectations, and hear from current students about their experiences in the past school year.

Instead, thanks to the pandemic, the moment turned virtual. Only a couple dozen eighth graders and their parents joined in the May 20 video call, with some listening to a Spanish translation. The president of Middlesex County College, where the students were to attend summer classes, told the youths he looked forward to seeing them eventually walk across his stage upon graduation. The head of Jingoli & Sons—a program partner—expressed hope some would work for his Mercer County-based construction firm when they had completed their coursework.

Michael Fanelli, the enthusiastic principal of the new six-year school, reminded the students they would graduate with an associate degree in electrical or mechanical engineering technology. The degree would be tuition free—and could lead to a job with salaries starting at $45,000–$55,000 a year. They could also transfer to New Jersey Institute of Technology, which had agreed to accept all of their college-level credits.

As for classes in the upcoming school year, they would be taking four a day, 80 minutes each, with an average class size of 13. “Ten days removed from eighth grade,” said Fanelli, “you’ll be with a college professor in a college-level class.”

Principal Michael Fanelli huddles with New Brunswick schools official Virginia Lagos-Hill, left, and student Cinithia Martinez Ramos. Photo by Frank Veronsky

The school, called New Brunswick P-TECH (Pathways in Technology Early College High School), is part of a national reform model developed in part by IBM and introduced in 2011 in New York City.

Under the P-TECH model, a public school partners with a local community college and relevant businesses to provide students a high school diploma, a tuition-free associate degree, and first-in-line interview for an entry-level job at one of the partner companies in the STEM fields: science, technology, engineering and math. For their local districts, the schools require no significant additional expenditures and no changes in union rules.

There are 220 P-TECH schools operating in 11 states and 24 countries. In the past school year, with the help of a state grant, the first three such schools opened in New Jersey—in Burlington City, New Brunswick and Paterson. A fourth school, in Trenton, is in the planning stages.

New Brunswick P-TECH, located in a refurbished warehouse, plans to admit 40 students each year. The school focuses on engineering; in addition to Jingoli, its corporate partners are the Canadian Global Information consulting company, CGI and North Carolina-based Cornerstone Building Brands.

Jaszymn Perry is one of the 40 students in the initial class at New Brunswick P-TECH, one of the first three New Jersey high schools that have adapted the unique six-year learning program. Photo by Frank Veronsky

P-TECH schools have no prerequisites for admission. As a result, they see students with widely varying abilities. At New Brunswick P-TECH, only seven students in the inaugural class were performing at grade level in math at the beginning of the school year.

Students enter P-TECH schools in grade 9 and begin a college-level course the first day, in intro to engineering design. By the final two years, all coursework is college level; some students who meet proficiency benchmarks can move through the program at an accelerated pace and finish in four years.

New Jersey Monthly followed the progress at New Brunswick P-TECH from before opening day last September through this spring’s statewide coronavirus shutdown. Here’s a look at the school’s eventful first year:

Govenor Phil Murphy at the P-TECH ribbon cutting. With Murphy, from left: Student Jazsymn Perry; former education commissioner Lamont Repollet (now president of Kean University); New Brunswick Mayor James Cahill; Zakiya Smith Ellis, Murphy’s chief policy advisor; P-TECH principal Michael Fanelli; and student Kevin Solis Pena. Photo by Frank Veronsky

SEPTEMBER

Governor Phil Murphy kicked off the school year with a high-octane surprise, attending the first day of classes. The governor told the staff and students that innovative companies looking to settle in New Jersey always inquire about the pipeline of potential employees.

“With P-TECH, they will see that we are filling our pipeline with tremendous and diverse talent,” said Murphy.

That day, as Murphy cut the ribbon to the school, freshman Johnce Cruz was both nervous—“maybe I didn’t look good enough or felt like I didn’t fit in for a couple seconds”—and excited. Johnce (pronounced JOHN-say), who sports an attentive expression and, often, a green beanie, had never changed schools before. Seeing all the new faces and new teachers felt weird at first. But he had enjoyed P-TECH’s summer bridge program, where instructors from Middlesex County College led English classes.

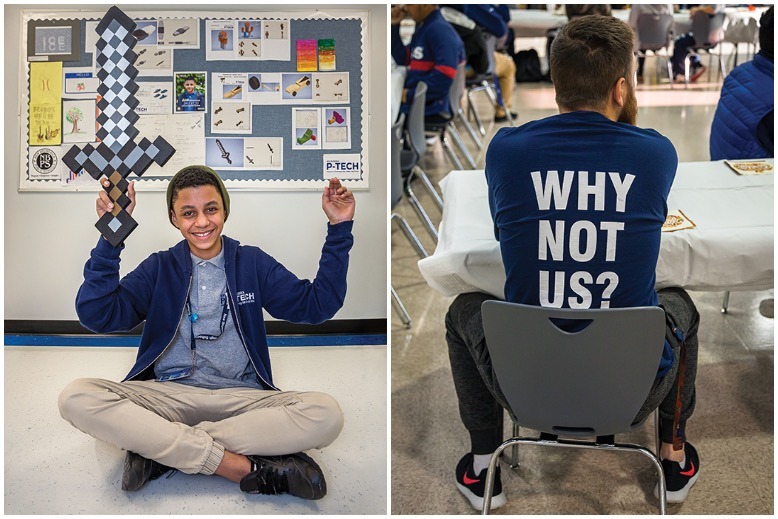

From left: Student Johnce Cruz shows off a sword from the popular Mindcraft videogame; a T-shirt worn by physical education teacher Kevin Hoagland makes a different kind of point. Photos by Frank Veronsky

“I felt good, like an adult,” he said of the opportunity to learn from college teachers. The classes were challenging, but he felt he could manage. (After all, he used to put Lego sets together without the instructions.) “It requires effort and determination,” Cruz said.

Toward the end of the first week of school, students in Nicole Grafanakis’s Soft Skills class, which focuses on the soft skills needed in the workplace, were watching TED talks and practicing two-minute presentations on a topic of their choice. Soon, they would produce PowerPoint presentations. Initially, they were amazed at how long two minutes lasted. Grafanakis, a first-time teacher with a graduate degree from the College of New Jersey, was glad to hear one student, Diego, say the class felt “like family.” The students were becoming comfortable with each other.

OCTOBER

The quality of Johnce’s eye contact seemed to have quadrupled. The previous school year, he had had to drag himself to school. At P-TECH, he looked forward to his classes. “Whether it’s a good day or a bad day,” he said, “I know it’s a school that’s new, something not like any other, and I’m proud to be a part of it.”

Down the hall, Fanelli and members of his team were meeting with partner companies to learn more about the skills the businesses sought in entry-level employees.

“Four, five or six years from now, I hope you’re all here in a cage match fighting for our students,” said Fanelli.

For at least one of CGI’s vice presidents, the collaboration had been eye-opening. “They had never even considered hiring people with just an associate’s degree,” said Fanelli. For the P-TECH partnership, they were realigning their requirements.

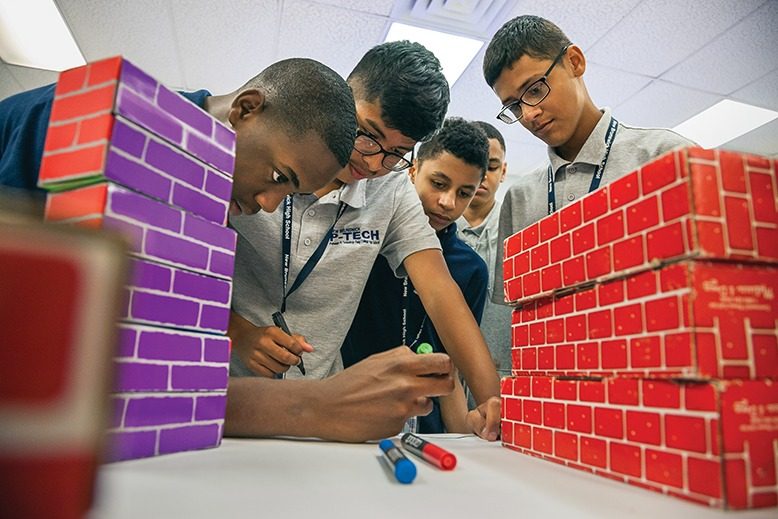

Photo by Frank Veronsky

NOVEMBER

On November 21, Fanelli and his leadership team had one of their monthly check-in meetings with local school district administrators at the city’s Board of Education offices. There were issues to report, but they were being dealt with.

Early on, a number of students had been failing classes; some seemed apathetic. A number of the girls were torn between schoolwork and taking care of younger siblings or keeping house for their working parents. At Superintendent Aubrey Johnson’s suggestion, the school had created an after-school program three days a week, with funding in part from an unfilled teaching position. The after-school program gave students time to finish their homework or get extra help before going home to their responsibilities.

At the meeting, Fanelli was able to report an improved culture and climate in the students and staff, which he attributed in part to the after-school program. “They just walked in and sat down as if it was lunch,” he said. As grades improved, teachers also got a lift; they could see that the program was on track.

Jamie Gulotta, the 6 through 12 district math supervisor, spoke about five students receiving extra help with math. Johnson was pleased to learn that the students—all of whom he knew by name—could make up work, but he raised a new concern. If test retakes were allowed in P-TECH but not at New Brunswick High School, others might complain. His solution: He would like other principals to emulate the close attention P-TECH paid to failing students.

Johnson’s thinking fit with a favorite Fanelli maxim: “The most dangerous phrase in the English language is, ‘We’ve always done it this way.’”

Fanelli reiterated his satisfaction with student culture and performance. “I’m watching their grades improve; the teachers are seeing, okay, it’s working,” he said.

“Can we push the ones who are excelling?” asked Johnson, whose questions often began with those three words. Three students, Fanelli said, were looking to accelerate, perhaps by taking an additional class.

Johnson had questions about every agenda item: Can we push students who are struggling in science? Are the parents aware of what we’re doing? Can you put video games in the curriculum? Often, it turned out that such initiatives were underway. Before the meeting was over, each administrator at the table confirmed which three students he or she would mentor.

Near the end of the meeting, Keira Scussa, assistant superintendent for curriculum and instruction, wished aloud for a P-TECH Friendsgiving the following week, with everyone bringing in a dish. She offered to cook a turkey; Fanelli volunteered for apple pie. Instructional technology supervisor Carla Segarra called pumpkin. But the superintendent worried again that other schools would feel jealous of P-TECH. Further, he warned against home-cooked turkey, which could become contaminated or cause allergic reactions. The idea was put on hold.

Meanwhile, a few blocks away at P-TECH, the students were getting ready to meet their mentors. They’d created dream résumés for applying to the partner companies. Johnce reported a 4.1 GPA (he was at 3.7 at the moment, pulled down by a B minus in algebra). His presentation included his work on revitalizing old pinewood derby cars, the 5-ounce race cars Boy Scouts engineer for maximum speed.

The Tuesday before Thanksgiving, the staff managed to pull off the proposed holiday celebration. Rather than home cooking, the cafeteria prepared turkey for 60 with all the trimmings. At the celebration, each student gave a presentation of the work on his or her hallway bulletin board—the work they felt most proud of. It was practice for when they would meet their corporate mentors the following month.

“I told them, ‘Don’t take this lightly,’” said Johnson. “Every time you speak, you’re interviewing, even from ninth grade.” The corporate mentors are always looking for promising students, he said, “so always talk up, be engaged, and be part of the process.”

Student Kevin Rodriguez, right, explains his bulletin board projects to his mentor, Katherine Villalona, a secretary in the New Brunswick school system. Photo by Frank Veronsky

DECEMBER

Fanelli arrived early on Mentorship Day and huddled with the teachers about putting extra emphasis on the school uniform that day, including a “no-hoodie rule.” He also suggested separating two kids who tended to be troublemakers. Once the program started, the students and their mentors visited activity tables, including 3-D tic-tac-toe, played with green and red plastic cups in three sizes, with larger cups able to commandeer the spots of smaller ones.

Johnce explained his bulletin board to his mentor, Connor Paladino, community outreach coordinator at Jingoli. He showed computer-generated plans for a classic Thunderbird car, including an exploded view of its separate parts. Johnce’s classmate, Norberto, described a drawing he’d made of various adventures in his life, including swallowing a battery as a toddler. He also showed the person-of-the-year magazine cover the students had been assigned to create. His was a picture of himself with the headline: “Man Finds a Solution for Global Warming.”

JANUARY

After the holiday break, the students visited the Wall Street offices of CGI. Only three had ever been to New York City, about an hour away by train. One student, Anita, crossed herself several times in preparation for her first elevator ride. As Johnce warily peered down from the 15th-floor windows, one of his friends jokingly pushed him from behind. Johnce said he thought he’d have a heart attack. After hearing from new CGI employees about their first year on the job and practicing brainstorming in small groups, the students began to relax in the corporate surroundings.

MARCH

Throughout the year, the staff had often used the Silicon Valley boast that they were “building the plane while flying it.” Then came the Covid-19 pandemic and the statewide shutdown. “In the middle of the flight, they told us we had to jump,” said Fanelli. “We’ve been building our parachute while we’re falling.”

The district had arranged for Internet connections for all its students pre-Covid. During the shutdown, teachers provided live and prerecorded online lessons. P-TECH students were already somewhat comfortable with the video technology. For Johnce, it only took a few weeks to adapt to online learning. He was even able to help his 18-year-old sister, a high school senior, get online.

[RELATED: Local Educators Reflect on Virtual Teaching]

Unfortunately, other opportunities for learning were limited. All the field trips planned for the spring were canceled, including visits to Middlesex County College. Extracurricular activities also suffered. The week before the Covid-19 crisis closed the school, Johnce had made the baseball team. Then the season evaporated. P-TECH would be holding online gym classes over the summer to help students rack up credits, but spring was coming, and Johnce didn’t like being so sedentary.

MAY

As the school year ground to a close, the volume of online work sometimes felt overwhelming. “Work kind of overlapped on top of more work,” said Johnce. To help students keep track of assignments, the teachers posted schedules online on Google Classroom.

Among the month’s new challenges: mastering the software for three-dimensional game design. The engineering teacher, Victor Alegria, had students design their own face shields. Johnce created his from a take-out food container.

Despite the upheaval of the pandemic, P-TECH New Brunswick staff could cite meaningful milestones. All but one P-TECH student passed the math course, compared to only 8 percent of students at the mainstream New Brunswick High School who were performing at grade level. Very few F’s were given as final grades all year—and the failing students would be able to make up those courses. On average, P-TECH students missed 2.83 days during the school year, the fewest average days missed in any of the district’s K-12 schools. As well, the P-TECH students earned a total of 117 college credits in their engineering design class.

Johnson, the district superintendent, was pleased with the students’ opportunities to interact with professionals in the engineering field, including female engineers and mentors who provided encouragement to the freshman girls.

He also noted that frequent meetings helped administrators look at student outcomes without blaming the students when they fell short. “We asked, ‘What can we do differently for them to succeed,’ and put the onus on ourselves,” he said.

JUNE

With the school year ending, Johnce was already looking forward to his summer classes and meeting new teachers. He remembered only one moment of panic from the past year, just as online learning started. He was concerned his grades would suffer.

“I think I was overreacting,” said Johnce. Indeed, he earned straight A’s. “I’m trying to keep that throughout all the years.”

During the Covid-19 shutdown, Fanelli missed the company of students. But he was pleased that his young staff proved fearless and adaptable. “I couldn’t be prouder of all those people,” he said.

Looking ahead, Fanelli described plans for this fall’s virtual learning, including the distribution of drones for students to program.

“The thing I’m proudest of is”—he paused, to compose himself—“those kids want to be there. That, to me, is the most important thing.”

Tina Kelley is a frequent contributor. She lives in Maplewood.