Cornelia Hancock, far right, at the time of the Civil War. Bottom right: Camp Letterman, the field hospital where she served at Gettysburg. Photo and illustration: Doug Stern

“There are no words in the English language to express the sufferings I witnessed today.” So wrote Cornelia Hancock, a 23-year-old Quaker nurse from Salem County, in a letter to a cousin. The letter is dated July 7, 1863, four days after the Battle of Gettysburg, the monumental engagement in south-central Pennsylvania that turned the Civil War in favor of the Union cause.

Cornelia, eager to assist her country, almost willed herself to the battlefield where so many had fallen. “I was the first woman who reached the Second Corps after the three days of fighting,” Cornelia wrote. She learned later that 2,000 men of the Second Corps had been wounded in the battle. “It is very beautiful, rolling country here,” she told her cousin, “but now, for five miles around, there is an awful smell of putrefaction.”

In letters to family members and friends over the following days and weeks, Cornelia described the suffering of the wounded, the care they received, and alas, the last minutes and hours of those they could not save.

Cornelia wasn’t supposed to be at Gettysburg. She wasn’t even supposed to be a nurse assigned to the Union Army. Those in charge dismissed her as too young and too pretty. But she would not be denied. “After my brother and every male relative and friend that we possessed had gone to the war, I deliberately came to the conclusion that I, too, would go and serve my country.”

Family members were not surprised at Cornelia’s determination to go join the war effort. Her father, Thomas Hancock, knew Cornelia could grow fidgety. At such times, he would tell her that she reminded him of her maternal grandmother, for whom “no kettle could pour fast enough to suit her without she tipped it over.”

On the morning of July 3, 1863, Cornelia was beyond fidgety. She wrote in her diary: “It seemed to me that the teakettle of life was pouring out very slowly indeed its scalding stream of anxiety, woe and endless waiting.” She would tip it over.

After deciding that she had to serve her country in some capacity, Cornelia traveled to Philadelphia to seek guidance from her sister’s husband, Dr. Henry T. Child, a prominent philanthropist who was active in the antislavery movement. “He promised to let me know of the first available opportunity to be of use,” Cornelia wrote in her memoir. She didn’t have to wait long. “The summons came on the morning of [July 5] when his horse and carriage was sent for me. When it was driven up in front of our house, my mother threw up both of her hands and exclaimed to father, ‘Oh, Tom. What has happened?’ I had not risen, but hearing mother’s exclamation and surmising, I said, ‘Oh nothing, mother. Doctor has sent for me to go to war!’” An hour later, she was on her way.

Stopping in Philadelphia, she began to hear details of the horrendous battle. “Every hour was bringing tidings of the awful loss of life on both sides,” Cornelia recalled in her memoir. The next stop was Baltimore, from which Gettysburg could be reached by train.

Dr. Child and the other physicians had recruited a few volunteer nurses to accompany them to the battlefield. “The ladies in the party were many years older than myself,” Cornelia wrote. The doctors and nurses arrived in Baltimore in the early morning. Shortly thereafter they encountered Dorothea Dix.

Two years earlier, Dix, then 59, had been appointed superintendent of female Army nurses. It was a giant step for both the Army and Dix. The military was accustomed to male nurses, and she had to reassure Army brass that female nurses would not unduly upset male patients. Consequently, she drafted strict guidelines for recruiting nurses. Applicants had to be over 30 years of age, “plain-looking” and dressed in “modest black or brown skirts.” She forbade skirt hoops and jewelry. Dix acquired the nickname Dragon Dix because, according to one description at the time, she was “stern and brusque.”

Cornelia described her first encounter with Dragon Dix: “She looked the nurses over and pronounced them all suitable except me. She immediately objected to my going farther on [account] of my youth and rosy cheeks.” Dix and another older nurse, Eliza Farnham, went into conference, evidently to discuss whether Cornelia could somehow be admitted to the nurse corps despite her youth and good looks.

Cornelia made her own decision. “The discussion [between the two women] waxed warm, and I have no idea what conclusion they came to, for I settled the question myself by getting on the [railroad] car and staying in my seat until the train pulled out of the city of Baltimore. They had not forcibly taken me from the train, so I got into Gettysburg the night of July sixth—where the need was so great that there was no further cavil about age.”

The battle of Gettysburg began July 1 and ended two days later with General Robert E. Lee’s Confederate Army beating a bedraggled retreat to the South. The casualty lists for both armies were long and horrific. Lee’s Army counted approximately 3,903 men killed, 18,735 wounded and 5,425 missing. The Union tallied 3,155 men killed, 14,529 wounded and 5,365 missing.

Cornelia’s first encounter with the overwhelming tide of suffering came at a makeshift hospital in a Gettysburg church. “Hundreds of desperately wounded men were stretched out on boards laid across the high-backed pews as closely as they could be packed together…. I seemed to stand breast high in a sea of anguish.”

She spent the next day at a field hospital containing “about 500 wounded.” She was the only nurse present; “not another woman within a half mile,” she told a cousin in a letter written July 7. Four surgeons “were busy all day amputating legs and arms.” Among the wounded were many Confederate soldiers, known as Johnny rebels. “I have one tent of Johnnies in my ward, but I am not obliged to give them anything but whiskey,” she wrote in her diary.

Eventually, the Union Army established a large general hospital—Camp Letterman—outside of town, where Cornelia labored until early September. In a letter written soon after her arrival at Camp Letterman, Cornelia advised her sister not to bother directing letters to “Miss Cornelia Hancock,” since she was known simply as Hancock.

Caring for the wounded at Camp Letterman usually occupied Cornelia 10 hours a day. In a letter to her mother dated August 17, she reported her displeasure with Army conventions: “I am alive and well, doing duty still in the general hospital. I do think military matters are enough to aggravate a saint. We no sooner get a good physician than an order comes to remove, promote, demote or something. Everything seems to be done to aggravate the wounded. There are many hardships that soldiers have to endure that cannot be explained unless experienced.”

While regularly reporting on the tribulations of her patients, Cornelia rarely mentioned the toll their suffering took on her. “I have nothing to do in the hospital after dark, which is well with me,” she wrote to her mother. “All the skin is off my toes…. I am not tired of being here; [I] feel so much interest in the men under my charge. The friends of men who have died seem so grateful to me for the little that it was in my power to do for them. I saw a man die in half a minute from the effects of chloroform [used as an anesthetic]; there is nothing that has affected me so much since I have been here. It seems like almost deliberate murder.”

In one of her last letters home from Gettysburg, addressed to her mother, Cornelia wrote, “One of my best men died yesterday…. He was the one who said if there was a heaven, I would go to it. I hope he will get there before I do.”

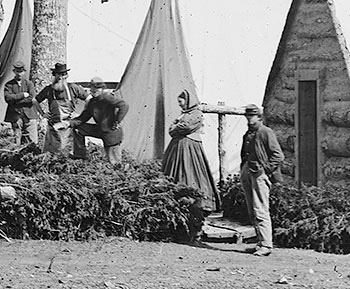

Arms folded, Cornelia Hancock stands outside a tent at the Virginia hospital encampment in the winter following Gettysburg. Photo: Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Cornelia left Camp Letterman in early September. She spent some time at home in Salem County, then took the train to Washington, where she cared for former slave families who had fled Southern plantations. She later served as a nurse in Union Army encampments in Virginia. In 1866, relying on donations from Philadelphia Quakers, she opened a school for freed Negroes in South Carolina. She taught there for nearly 10 years.

As time passed, more than a few of the soldiers Cornelia attended at Gettysburg corresponded with her after being discharged from the hospital to go home or back to camp. One, who signed his letter, “Your sincere friend, a Soldier,” thanked her for “kindness to our poor wounded comrades. You will never be forgotten by us, for we often think of your kind acts and remember them with pleasure.”

Cornelia never married and never admitted to having an affair, but many have speculated that she fell in love with a Union Army doctor from Connecticut named Frederick Dudley and that he returned her affection.

Cornelia Hancock died in 1926. She was 87. On the night table alongside her bed was a packet of letters wrapped in a paper on which she had written, “Burn without reading.”

Charles H. Harrison is a Salem County-based journalist and author of the Civil War novel No Longer Warriors (PublishAmerica, 2003).