East Orange architect Edward Bowser Jr. is not widely recognized, but his buildings are hard to forget. Their glass walls, flat roofs and minimalist design stand apart and invite comparisons to Frank Lloyd Wright.

That makes sense, given that he apprenticed with the preeminent architect of his time, Le Corbusier, a pioneer of modern architecture who designed the United Nations headquarters in New York and other famous buildings.

Bowser was the first African American architect to work with the renowned French modernist, and among the first Black architects to work in New Jersey. But the road to becoming an architect wasn’t easy for him. According to his brother, Robert, New Jersey would not test him for an architectural license, so instead he took a national exam through the National Institute of Architects and got the highest score in the country.

“He was as close to a genius as you could be,” Robert Bowser said of his brother, who also taught himself photography and learned to pilot a plane.

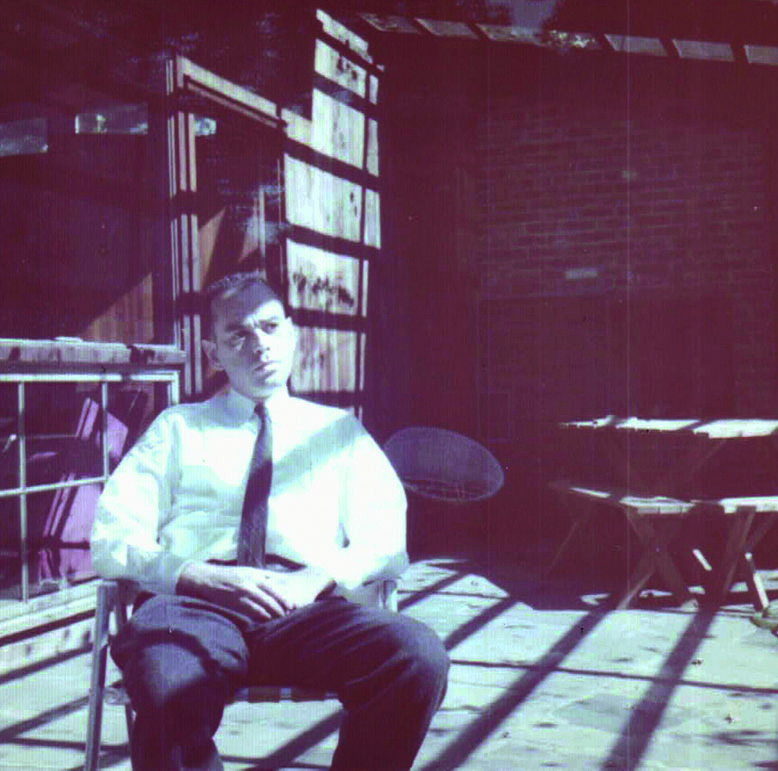

Bowser in his early years as an architect. Photo courtesy of the Bowser family

There are at least a dozen houses and buildings in New Jersey that were designed by Bowser, including the headquarters of the cigarette-lighter company, Ronson Corporation, in central New Jersey, the Medical Arts Building in East Orange, a ShopRite supermarket, and many residences throughout Essex County.

Frank Godlewski, also an architect, owns a home in Essex Fells that Bowser designed in 1957. He has been working to have Bowser’s name recognized in the field and recently delivered a lecture about Bowser to a class at Princeton University’s School of Architecture. He told the class that Bowser’s story is important architectural history, before making a correction: “It’s important American history that has not found its place yet.”

Bowser was born in 1925 and grew up in East Orange, one of four boys. Design, building and engineering ran in the family. His father, Edward Sr., was an architectural draftsman and earned his architect’s license after Edward Jr. did. His brother, Hamilton, was a structural engineer and owned EvanBow construction company. Lucius was the only outlier; he was a pharmacist. The youngest brother, Robert Bowser, was a municipal planner and the mayor of East Orange for four terms. (He died in February at the age of 86, shortly after having been interviewed for this article.)

***

Public service is also a part of the Bowser family legacy. Edward Bowser Sr. served on the East Orange city council, in the New Jersey Assembly and on the Board of Police Commissioners. In 2000, East Orange named an elementary school after him. Each of the Bowser sons served in the military; Edward Bowser Jr. served in the Navy.

The residences that Bowser designed in New Jersey are located in Montclair, Essex Fells, Nutley, West Orange and North Caldwell, and range from two- to four-bedroom houses.

Godlewski is an enthusiastic admirer of Bowser’s work, and that includes his own residence.

“Compositionally, it’s a very poetic gesture and purely Le Corbusier inspired,” says Godlewski of his home. “This was sort of a concept house.”

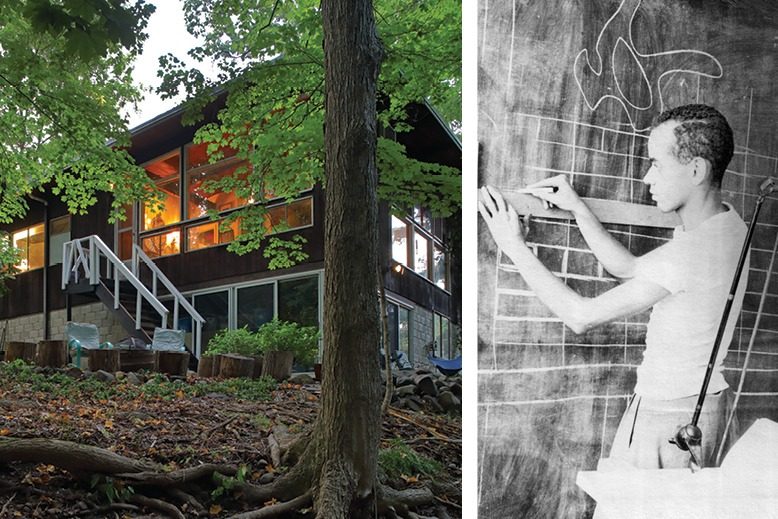

It’s based on the nine-square-grid layout that Le Corbusier, the Swiss-French architect, devised as a learning tool to teach architects the dynamics of design, says Godlewski. The house is perched on his property, a former mill pond, like a glass box nestled between a brook and a road.

“The structural elements disappear the closer you get to the brook,” Godlewski says. “It’s a house that turns its back to the civilization and just flows into the nature.”

Another house that Bowser designed, in Nutley, has a full view of the Manhattan skyline from a 25-foot-wide window that floods the upper floor with light. Glenn Mariconda, a clothing designer, moved into the house last year with his wife, Asaka Midorikawa Mariconda, and their two-year-old son.

The Nutley home that Bowser designed is now owned by Glenn Mariconda and his wife, Asaka Midorikawa Mariconda. Photo by Matt Wargo

“It’s a very modestly built house, but you want to be in it,” Mariconda says. “We felt like we wanted to live here the minute we saw it.”

His house and the one next door, also designed by Bowser, stand like unobtrusive sentinels overlooking the postwar neighborhood.

Mariconda’s kitchen has double-sided cabinets and a pass-through similar to those designed by Le Corbusier. The French modernist’s influence is clear, but the house is “truly unique,” Mariconda says. “What we loved about this house is it was inspiring, but completely practical.”

Fascinated with the house and the story behind it, Mariconda reached out to the Le Corbursier Foundation to find out what they knew about Bowser. “It’s hard to believe [Bowser] is not well known or better known,” he says.

The interior of the Nutley house. Photo courtesy of Glenn Mariconda

Godlewski was similarly intrigued with his own house, which he now calls Fellsbridge, and looked up the original drawings in search of the architect’s name.

***

After graduating from East Orange High School in 1943, Bowser Jr. attended Howard University in Washington, DC. There, he met his wife, Carmen Willette, a fashion design major from Belleville. He transferred to Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in New York, where he graduated from the school of architecture in 1948.

The following year, Bowser traveled to Paris, where he apprenticed at the famous Le Corbusier design studio at 35 Rue de Sèvres. He worked there from 1949 to 1950.

“He has worked with much precision and seriousness, quite particularly while working on L’Unite d’Habitation de Marseille,” Le Corbusier wrote in a letter of reference for Bowser in May 1950. L’Unite was the most famous of Le Corbusier’s modernist residential housing. It formed the basis of housing developments throughout Europe and was added to the UNESCO World Heritage list in 2016.

After leaving Le Corbusier’s studio, Bowser stayed on in Europe, designing postwar reconstruction projects and beginning a family with his wife. Their first child, Kathryn, was born in Paris in 1950. Bowser and his small family returned to New Jersey around 1952, and they later had two more children, Cecile and Edward III.

He built his new family a home that was located a stone’s throw from the home he grew up in on Oak Street in East Orange. His daughter, Cecile, called it “a modern house in a colonial city.” At the time, it was considered an anomaly in the town. “We had a heated flagstone floor and a chimney on the inside of the house. There were a lot of 1950s modern elements to that house,” says Kathryn, now a graphic designer in New York City. The house doubled as an office for Bowser’s architectural firm.

When outrage over racial injustice swept across the country and made its way to nearby Newark in 1967, the uprisings motivated Bowser to get involved.

“My father became pretty involved in housing and other economic issues,” Kathryn says.

***

This activism inspired Bowser to design the Kuzuri Kijiji Housing Development on Freeway Drive in East Orange for low- and middle-income families. Kuzuri Kijiji, which means “beautiful village” in Swahili, was noted in 1973 by Jet magazine as “the largest housing development in the United States developed by blacks.” Bowser designed each of the 200-plus town houses with individually landscaped yards.

In the late 1970s, Bowser and Carmen moved to Ghana; after the country gained independence in the 1950s, it attracted many African American intellectuals and Civil Rights activists. Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X and Maya Angelou all made pilgrimages there. In Ghana, the Bowsers developed Mampong Akuapem Polytechnic Institute, a vocational school about 20 miles outside of Accra. Carmen started the design branch of the school and “created a variety of ceremonial costumes, while also teaching the women in the community how to sew,” Robert says. Ghana’s leader and later president, Colonel Jerry Rawlings, was supportive of the program. He and Bowser bonded over their common love of flying; they even constructed an airplane together out of parts they found, and used the plane to visit developing villages, says Robert.

“He was very community minded and was named as a tribal chief there,” his daughter, Cecile, says. He died of malaria in 1995. His wife, Carmen, died in 2013.

They are both buried in Ghana.

Dionne Ford is a frequent contributor to New Jersey Monthly.