Since 2000, Gabriel Jason Dean’s half brother, a convicted murderer, has been locked up. While in prison, he became involved in alt-right thinking. Eventually, Dean pulled away.

“He was telling me all the virtues of Mein Kampf and really believing that,” says Dean. “I couldn’t stomach it.”

Dean last visited his sibling in 2005 before cutting off most communication for about a decade. Then, when Donald Trump was elected president in 2016, Dean decided to reach out again.

“White nationalism had a voice in the White House,” says Dean. “I started really feeling like I needed to reach out to [my brother] because I know that he’s surrounded by this on the inside, but now he’s seeing it on the outside, too.”

Dean knew reconnecting would come with challenges. “I vowed to listen,” says Dean, “which was not easy to do, but transformation has occurred, I think, as a result of that.”

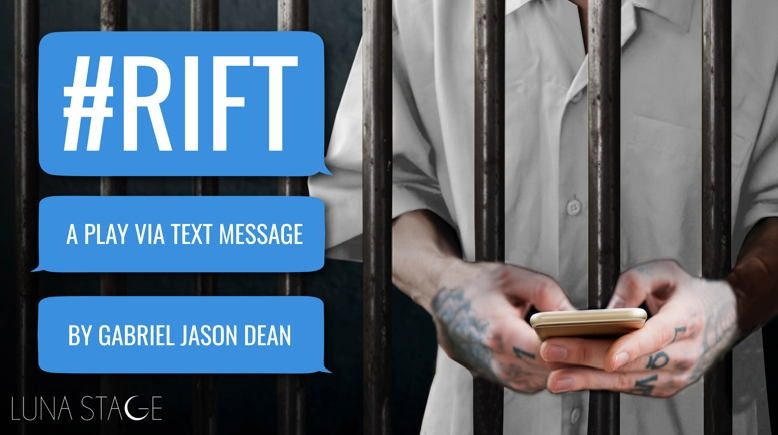

Dean’s reunion and relationship with his brother is the subject of his new play, #RIFT. Presented by Luna Stage in West Orange, the project will be a monthslong theatrical experience in three parts. The first part, beginning April 9, will be a durational play delivered via text message for free. (Audiences can sign up through April 23, while space is available. Patrons will be grouped into cohorts so that those who register past April 9 will still receive the same experience.)

Roughly twice a week, audience members will receive real correspondence between the brothers, including photos of handwritten letters as well as screenshots of text conversations and emails. Some messages will be recordings of Dean’s voice; he sometimes used his “dramatic toolkit” and reimagined phone conversations with his brother. A dramaturg will act as a concierge, guiding the audience’s experience.

[RELATED: In the Dark: What Lies Ahead for Jersey’s Arts Institutions?]

“We’re kind of inventing this form,” says Dean. “It does have the components of a play, but you’re going to have a different relationship to the material than you would if you were watching.”

“That’s the experiment,” he adds. “We’re blending different literary forms together and seeing what that whole experience yields.”

The texts will be sent between 10 am and 7 pm. Dean originally wanted Luna Stage audiences to receive messages at off times, mimicking the weird hours in which he has had to interact with his brother.

Playwright Gabriel Jason Dean

When developing the text message component, Dean, who lives in Brooklyn with his wife and two children, was inspired by the ways in which technology has allowed him to reconnect with his brother.

“Texting has been a way for us to really work some stuff out,” says Dean. “If you listen to our live conversations, we just don’t get deep because I think it’s too hard, honestly.”

Dean admits that, as a playwright, written communication comes more naturally for him. Although his brother is not a writer, texting, “forces him to think about it [and] to be honest with himself,” says Dean.

Throughout their renewed relationship, change has occurred on both ends, says Dean.

“I certainly have not become a white supremacist, but I have a deeper and more profound understanding of where he is coming from than I initially did,” says Dean.

At first, Dean had his reservations about exposing the details of his relationship with his brother during the current era of social and political reckoning. His thought process was along the lines of: “Who wants to hear the story about two white guys who are struggling with whiteness right now?”

But his perspective shifted while reading James Baldwin’s 1962 essay, Letter From a Region in My Mind. One sentence in particular struck him: “White people in this country will have quite enough to do in learning how to accept and love themselves and each other, and when they have achieved this—which will not be tomorrow and may very well be never—the Negro problem will no longer exist, for it will no longer be needed.”

“That blew my mind,” says Dean. “It was almost as though, not to [be] too grandiose about it, but [it’s] like [Baldwin] was giving me permission in that essay to do this…That that’s actually the root of this problem—a problem that needs to be worked out between white people and specifically, I think, white men.”

Dean notes that over the past few years, much of the work he’s read that focuses on racism, social justice and white supremacy has been almost exclusively written by writers of color and women. “And that says something,” says Dean. “Where are the white guys? Why aren’t we showing up to this meeting also?”

Luna Stage in West Orange

Later this spring, Luna Stage will launch the second virtual component of Dean’s project. With the help of consultants, Dean crafted an exercise to show audience members how to have a civil conversation with someone with whom they disagree. (The dramaturg who serves as the narrator in the first component will request participation, also via text message.)

“We’re going to provide the audience with the tools and resources to be able to [have that conversation], hopefully productively, and listen to each other and see what happens,” says Dean.

Some of the audience feedback will be incorporated into the scenic and sound design for the third part of this project, a live theatrical performance at Luna Stage in West Orange in the fall. Audience members do not need to participate in the first two parts of the project to attend the live play, although it will enhance the experience, Dean says.

“The idea is that this is not just a story about me and my brother,” says Dean. “The piece, more than anything, is about making space when it’s uncomfortable to hear each other. Sitting in the same room even though you don’t think you’ll be able to see eye to eye—forcing that, forcing yourself to do that.”

Throughout the pandemic, the brothers have been speaking at least weekly via legal video chat. This spring, Dean plans to visit his brother in person for the first time in nearly two decades.