For a few hours on February 2, Frank Supovitz will be the most powerful man in America. He isn’t worth billions, and he doesn’t carry nuclear launch codes in his briefcase. It’s just that virtually everyone in the country, including the President of the United States and an expected 1 billion people worldwide, will be watching as Supovitz does his job that afternoon.

Frank Supovitz runs the Super Bowl.

As the NFL’s senior vice president of special events, Supovitz wields immense power, but in a remarkably low-key way. A soft-spoken man of medium height and build, he smiles easily and makes a point of sending handwritten thank you notes. Last summer, in the run up to Super Bowl XLVIII, the 56-year-old looked even less formidable after a serious leg injury (playing, of all things, flag football) put him on crutches. The injury kept him off airplanes for several months, a huge hindrance for a guy simultaneously juggling preparations for three Super Bowls—next month’s at the Meadowlands, 2015 and 2016.

On game day, Supovitz will ensconce himself in an undisclosed command post in the bowels of MetLife Stadium in East Rutherford. His job: Make sure the world’s most-watched single sporting event comes off without a hitch. But as he well knows, hitches happen. Supovitz has coped with a torrential downpour knocking out power moments before Prince’s halftime show (2007), fans pouring onto the field before the game was officially over (2008) and a major power outage at the Super Dome in New Orleans last year that shut down the game for a seemingly interminable 34 minutes.

“The Super Bowl is a living, breathing organism,” Supovitz says. “It’s subject to surprises at any corner and any level.”

In Supovitz’s office at NFL headquarters on Park Avenue in Manhattan, binders bulge with hundreds of pages of Super Bowl bid specs, safety requirements and enough standard operating procedures to put the Pentagon to shame. Yet every Super Bowl is unique. Which makes Super Bowl XLVIII, well, more unique. It’s the first to be held in an outdoor stadium in a winter climate, and the first to parachute its two-week movable feast of parties and promotions into a destination as densely populated and sprawlingly developed as the New York/New Jersey metropolitan area.

There are compelling reasons to award a Super Bowl to a cold-weather metropolis—chief among them to expand the pool of host cities, which heightens competition and leads them to sweeten their bid packages, often by building what the NFL most covets: big, new, state-of-the-art stadiums.

That the Jets and Giants built MetLife Stadium, which opened in 2010, has a lot to do with why the 2014 Super Bowl will be played on Garden State soil. It helped that the greater metropolitan area is one of the wealthiest in the country. As a result, the league gave the nod. Now it’s fixing to take on Mother Nature like a fullback picking up a safety blitz.

“Every preparation has to be able to occur in the worst possible weather,” Supovitz explains. “We are very cognizant that we have to have a snow-removal plan that goes beyond plowing the highway approaches, the outdoor event sites and the pedestrian plazas. We have to have a plan to get the snow out of the seating bowl and off the field. If it’s not possible to admit people to the stadium because the snow arrived in great amounts at the last moment, we’ll have contingencies for that.”

As a hedge against nasty weather, the NFL has revamped Super Bowl Week in an unprecedented way. Media Day, which has become fan-centric in recent years, was moved from MetLife Stadium to indoors at Newark’s Prudential Center. MetLife’s formerly bare-bones security checkpoints will morph into heated Welcome Pavilions offering entertainment and merchandise—an idea, Supovitz confides, likely to find its way into future Super Bowls. The NFL will distribute 80,000 Warm Welcome care packages—featuring a commemorative seat cushion, hand warmer, muffler (like quarterbacks use), earmuffs, lip balm and a pack of tissues—one to each ticket holder.

You might think Supovitz and his crew have been poring over long-range forecasts, from computer models to the Farmer’s Almanac and comedian Bill Cosby’s big toe (the latter two predicting snow). You’d be wrong. “None of that really matters,” he says. “You know it could snow. You know it could be icy. You have to prepare for it as though it’s 100 percent certain.”

As much as Supovitz frets about a blizzard, he can take comfort that football games—including great ones like the 1967 NFL Championship Game now known as the Ice Bowl—have been played thrillingly in the worst weather imaginable. But the Bruno Mars extravaganza that will light up halftime at Super Bowl XLVIII?

That’s another matter. Under the best of circumstances, a Super Bowl halftime show is a high-wire act.

The stage, loaded with lights and special effects, needs to be assembled and trundled onto the field in less than eight minutes by volunteers on foot—tires could damage the precious turf. After the headliner blasts the known universe with 12 minutes of megahits, the stage has to be broken down and pushed off the field in under seven minutes as the second-half kickoff looms. Add the potential for snow, ice and swirling wind, and you can see why Supovitz and his team decided to ditch the status quo.

“We started working with the designers and producers of the halftime show more than a year ago to reinvent how it might be staged, so less will have to move onto the field during that eight minutes,” he explains. “A significant amount of the staging will actually be built into the wall of the stadium right behind the team benches, with a lot of the bells and whistles already installed. It won’t look like a halftime stage because it will be disguised by décor. It will look like it’s naturally there every Sunday.”

Then there’s the minor matter of moving a small city’s worth of visitors around an already congested metro area. “The number one challenge is the geographic footprint of the region,” says Al Kelly, 54, the American Express exec-turned-CEO of the Super Bowl Host Committee. “Everything is complicated by the fact that we’ve got a dozen or more counties, separated by the river. We’re moving a lot of people to and fro.”

So what’s the solution? “I learned a boatload about mass transit,” Kelly says with a laugh. He isn’t kidding. With the Super Bowl in mind, New Jersey Transit lengthened the lower platforms at Lautenberg Station in Secaucus by 120 feet to accommodate double-decker trains 10 cars long instead of the usual eight. It also expanded the number of bus slots from four to 14.

Road-widening and construction of a new Route 3 bridge over the Passaic River, just west of the stadium, was planned before the Super Bowl bid, and is scheduled to be completed this summer. Kelly says the ongoing roadwork will be coordinated to keep all lanes open for the game. Also hanging fire is the makeover of the multicolored Xanadu mall next to the stadium—promised in 2010 by Governor Chris Christie, who called it the “ugliest damn building in New Jersey, and maybe America.”

On a normal game day, MetLife Stadium and the rest of the sports complex can accommodate almost 29,000 cars. On Super Bowl Sunday, the number of parking spaces will be reduced to 11,000. Tailgating will be restricted. The acres of lost parking will be transformed into a security perimeter plus parking for satellite trucks and other support vehicles and the Welcome Pavilions with their security checkpoints.

The loss of fan parking is less a problem than it would be for a typical game, because most ticket holders are expected to fly in, then arrive at the stadium by public transportation. The area’s three large airports routinely handle Thanksgiving and Christmas crushes of up to 1.2 million travelers, so the anticipated Super Bowl influx of 400,000 should be a relative breeze.

Kelly is more concerned with VIPs. Recently expanded facilities at Newark Liberty Airport can handle up to 75 large private jets. Other private planes will touch down at small airports like Teterboro and Essex County in Fairfield. VIPs love arriving in limos, but drivers of those status symbols (and of so-called black cars and taxis) will have to buy access permits and remain in a secure lot until their passengers are ready to be picked up. “There’s a lot of messaging that has to go on,” Kelly concedes.

As mayor of East Rutherford, James Cassella makes $7,000 a year to run a town with a population of 8,913. But he’s poised for a promotion: In February, he’ll be the mayor of the Super Bowl. A Republican now in his fifth term, Cassella, 67, knows this game will be different for the town that lends MetLife Stadium a mailing address. And not entirely in a good way.

According to Cassella, East Rutherford will bear a disproportionate burden. Starting the Wednesday before the game, the town’s police resources will go on Super Bowl duty, with officers from the records and detective bureaus pitching in to patrol the streets.

“We deal with this continually, 20 weekends a year,” says police chief Larry Minda, “so nothing that will happen at the Super Bowl will catch us by surprise.”

The town’s Emergency Medical Services and fire department (both volunteer) will also be all-hands-on-deck. If that Cosby-predicted snowstorm happens on the weekend of the game, Cassella will be looking at paying crews double-time to plow the streets near the stadium posthaste. Neighboring towns like Secaucus and Carlstadt will be in the same pickle. And they all will be doing it without help from the folks running the game.

“The NFL does have somewhat of an attitude,” he says. “‘You’re getting a Super Bowl. You should be honored.’ And they’re not giving you any money to do this.”

Nor is Paul Aronsohn, mayor of Ridgewood, feeling the love. The NFL designated his town, along with Montclair, an “official town of interest.” This odd appellation, like something slapped on a terror suspect, was meant to be a plum. But from Aronsohn’s perspective, Ridgewood has gotten all pit and no fruit. “We’ve done everything we can to be a part of this, and we really want to work with the NFL,” he says. “But it just doesn’t seem like it’s a two-way street.”

For his part, Cassella remains sanguine. He’s hoping for a quiet, snow-free day that won’t wreak havoc with the town’s $25.2 million budget. “We’re okay with this,” he says. “For 20 dates every season, we deal with football games. But I’ve said this from day one, that the NFL and Fox, which is covering it, will make this Super Bowl a New York event. MetLife Stadium is in East Rutherford, in Bergen County, in the state of New Jersey. And that shouldn’t be forgotten.”

If Supovitz has the most high-profile job on Super Bowl Sunday, the man who’ll sit next to him in the command center has the most nerve-racking one. That is Jeffrey Miller, the NFL’s chief of security. He spends the pre-game months in the land of the worst-case scenario.

“You’re only limited by your imagination,” he says grimly, when asked what keeps him up at night. He knows he must prepare for everything from a terrorist attack to a crazy with a grudge and a gun, from dirty bombs to chemical weapons—enough trauma for a whole season of Homeland. In fact, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security designates the Super Bowl a SEAR-1 (Special Event Assessment Rating 1), which is one notch below the two quadrennial political conventions. That puts a remarkable array of resources at Miller’s disposal.

“There are easily more than 50 different agencies and entities who are part of the process in one way or another,” he says. They range from the 40-officer East Rutherford Police Department to the Secret Service. In between floats a sea of acronyms—FBI, ATF, NSA, CIA—along with the New Jersey State Police, the lead law-enforcement agency. Military resources could include F-17 fighter jets and Blackhawk attack helicopters ready to scramble from locations such as McGuire Air Force Base, 70 miles south.

Miller is reluctant to talk about the largely invisible military presence, but his now-retired predecessor, Milt Ahlerich, will. “The protection from the air?” Ahlerich says. “I don’t know that I’d want to come to the game if that wasn’t in place.”

The high-level measures begin with erecting a hardened barrier of fencing, concrete roadway dividers (developed at Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken in the 1950s and known as Jersey barriers) and the stout, waist-high posts called bollards that block vehicles but let pedestrians pass. “People who have been to the stadium but are new to Super Bowls will say, ‘Wow, what’s all this?’” Miller says.

On game day, everyone will be screened with walk-through and hand-held metal detectors, pat-down searches, explosive-sniffing dogs and x-ray equipment. As at regular NFL games, backpacks will be banned and carry-in items will have to be placed in small, transparent pouches.

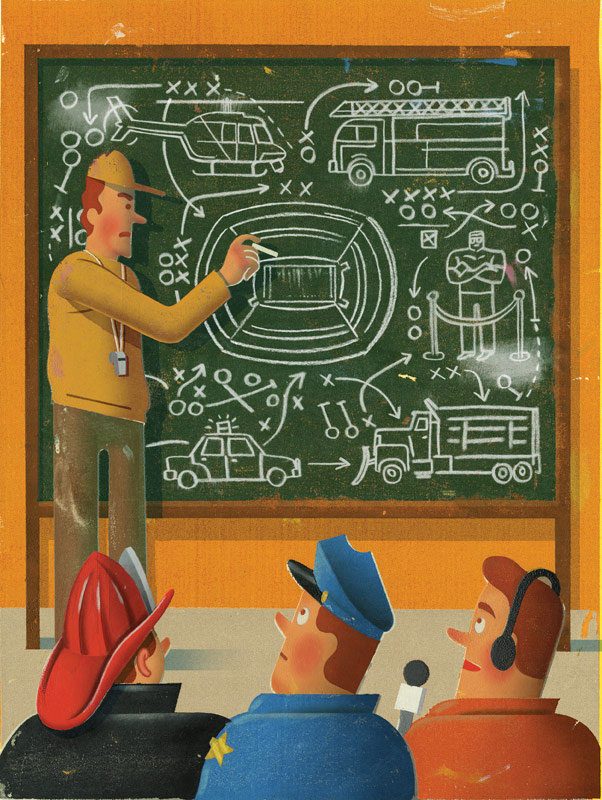

Ten days before kickoff, Miller, Supovitz and their teams will hunker down in the command post to run a series of worst-case simulations. “Game-day simulations will help you deal with a crisis, but not necessarily avoid a crisis,” says Supovitz. “They are designed to create a sense of teamwork, certainty and confidence in working through problems together. They will not prevent a toxic waste spill. They will not prevent a blackout. What they will do is help you understand how to solve these problems when they’re presented to you.”

The location of MetLife Stadium is a mixed blessing. On one hand, its relative isolation makes it simpler to secure than urban sites like the Superdome in New Orleans and Lucas Oil Stadium in Indianapolis. “It’s a little bit easier to do a secure perimeter when you don’t have parking garages and a post office and a courthouse intruding on that space,” Miller explains.

On the other hand, the reliance on mass transit is worrisome. A fully loaded NJ Transit train or a bus crawling through traffic in the Lincoln Tunnel make shudderingly tempting targets. “Certainly there’s a lot of transportation fears,” Miller says. “You’re always concerned about something happening in that regard.”

The proverbial lone gunman is also on his mind. He mentions the November incident at Garden State Plaza in Paramus in which a disturbed 20-year-old sprayed bullets in the air, creating chaos among shoppers, before killing himself. “That’s a very frightening prospect,” Miller says solemnly. “In a free society, it’s just not possible to have 100 percent safety.”

Violence is not the only public safety concern. Super Bowl cities usually see prostitution spike the week before the game. Sister Pat Daly and her fellow Dominican Sisters of Caldwell have joined a grassroots effort by the New Jersey Coalition Against Human Trafficking to contact managers at area hotels and heighten their awareness of the problem.

“It started with Catholic nuns in Dallas and Indianapolis, and now it’s a huge, huge network of volunteers,” Daly says. “There’ll be over 300 volunteers reaching out to over 1,000 hotels from Fairfield County to the Philadelphia area. We wanted to not only make them aware, but let them know what to look for. It could be happening right in front of their eyes.”

Eighteen megawatts. That amount of electricity will power 12,000 homes—or one Super Bowl. Keeping the juice flowing is yet another Supovitz obsession. “I learned an awful lot about how electricity is delivered to a stadium over the last year,” he says. “An education I probably would never have received had the lights not gone out at the Super Dome.”

PSE&G has been on a mission to make sure there is no repeat. “The halftime show, the tents, a lot of the broadcast—they’re going to be on generators,” says Bill Labos, PSE&G director of asset reliability. “A building has a certain power load, and the generators will [provide] anything above and beyond what’s normal.”

PSE&G installed two new transmission lines to back up the primary line, which runs from its East Rutherford substation to the substation at the sports complex. Each back-up line (in power biz argot, a death row feed) can carry the entire Super Bowl load if the primary were to fail.

The system was given a stress test in September. Under a full 18-megawatt load—lights, escalators, scoreboards, HVAC, everything in the sports complex running full blast for several hours—nothing failed but a minor circuit breaker in the Izod Center and a controller that drives a scoreboard in the stadium.

“Neither would have affected the game,” says Labos, a 41-year veteran. “We’ve actually taken infrared cameras and gone inside all the switch gear, looking for temperature differences that would indicate that wires are loose or incorrectly connected. We just wanted to make sure there wasn’t a guy who had accidentally dropped a screwdriver inside a panel that could trip the entire system out.”

Like Supovitz, PSE&G has done its own blizzard prep. The critical objects are the little white ceramic insulators you see on the cross arms of utility poles. “What’ll happen in an ice storm,” explains PSE&G president Ralph LaRossa, “is that sometimes the insulator will be dirty and it will [short circuit].” PSEG has been inspecting every insulator on every pole carrying power to the stadium. “You’ve got a thousand you’ve got to check,” LaRossa says.

Every Super Bowl leaves a legacy, be it a stunning, game-saving play or a mishap like last year’s blackout or Janet Jackson’s halftime wardrobe malfunction in Houston in 2004. It’s Jack Groh’s job to make sure Super Bowl XLVIII leaves no physical footprint. As NFL environmental director, Groh makes epic amounts of stuff safely vanish.

After the Lombardi Trophy is hoisted in the winning locker room, Groh will find a new home for an estimated 5 to 7 miles of fabric and vinyl used as drapery and bunting; scores of rolls of indoor/outdoor carpet used to line corporate tents and media centers; construction materials and leftover merchandise.

“In New Orleans,” he says, “they remanufactured the fabric and vinyl into tote bags, beanbag chairs, shower curtains, evening gowns, even palazzo pants. Here, we’re still hunting for the right combination of folks who can reuse it. People say, ‘Isn’t it a shame all this stuff gets thrown out after the Super Bowl?’ Actually, very little of it sees a landfill.”

In addition to spearheading a massive tree-planting project in 10 New Jersey counties, Groh has been gathering biodiesel to run generators at the stadium and overseeing construction of the Super Bowl’s first on-site composting operation. “Stuff that often goes into the waste stream at other events,” he says, “doesn’t go into the waste stream at the Super Bowl.”

The moment the last person and vehicle exit MetLife Stadium on February 2, people like Supovitz and Miller will shift focus to next year. So will Groh, who also thinks in a longer time scale. Thousands of years from now, as he sees it, archeologists will study landfills and unearth our refuse. He hopes his efforts will make them think just a little better of us.

Allen St. John’s books include The Billion Dollar Game, about the 2008 Super Bowl, and the new Newton’s Football: The Science Behind America’s Game, with Ainissa G. Ramirez, Ph.D. He lives in Montclair.