For several decades starting in the early 1960s, an economist and professor named Norton Dodge traveled frequently from his home in Maryland to the Soviet Union, ostensibly for academic work. In his travels, Dodge became fascinated with the anti-establishment art that was flourishing in the Soviet underground. Each time, before he flew home, he stuffed art in his suitcase or made arrangements to ship larger works. By the time the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, Dodge had smuggled out more than 10,000 pieces. He later acquired still more.

Last November, Dodge’s collection of Soviet nonconformist art landed at Rutgers’s Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Museum in New Brunswick. The windfall of 17,300 objects, valued at $34 million, is the largest single gift ever made to the university. Many of the pieces are now on display for the first time in America.

At a time when Russian secrecy and political maneuvering are consuming the U.S. imagination, the scores of paintings, drawings, photographs and sculpture on view at the Zimmerli serve as a reminder that, as museum director Tom Sokolowski says, “a government can be very different from the people it’s governing.”

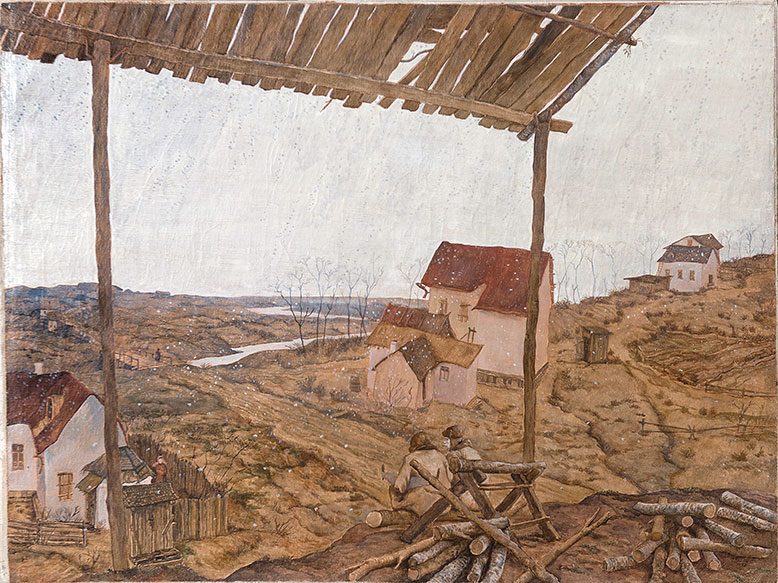

Soviet nonconformist art was made by citizens of what was then the USSR who refused to conform to the Cold War government’s restrictions. Abstract art, expressionism and conceptualism were outlawed. “Even kinetic art and geometric art” were off limits, says Julia Tulovsky, curator of Russian and Soviet nonconformist art at the museum. “Basically, everything that wasn’t socialist realism went underground.”

For context, the museum has hung several examples of socialist realism—the Soviets’ sanctioned art form—on the wall leading into the Zimmerli gallery permanently devoted to the Dodge collection. Essentially, they’re portraits of Soviet leaders accompanied by words of praise. “Standard bearer for the world,” reads one depiction of Stalin.

No wonder Dodge, the subject of John McPhee’s 1994 book The Ransom of Russian Art (Farrar, Straus and Giroux), wanted to elevate the dissident artists. An Oklahoman who ultimately amassed the largest collection of Soviet nonconformist art in the world, Dodge first traveled to Russia in 1955, as a Harvard doctoral candidate, to study the role of tractors in the Soviet economy. “He got acquainted by chance with someone who brought him to an exhibition of underground art, and he started to befriend the artists,” Tulovsky says. That led to his sideline as a smuggler. Some of the art he brought back was grim and oppression-obsessed, like Vasily Sitnikov’s untitled 1959 drawing of a ghostly woman with her mouth obscured. It’s on display in the gallery. Other pieces, like Boris Orlov’s The General, a colorful, painted-wood sculpture from 1982, manage to dilute strife with whimsy.

Dodge and wife, Nancy Ruyle Dodge, made an initial donation of 4,000 works to the Zimmerli in 1991. The Zimmerli already had a collection of Russian art, and Dodge saw it as an appropriate home for his illicit treasures, Sokolowski says. Dodge died in 2011 at age 84; his widow, now 81, donated the remaining 17,300 pieces to the Zimmerli. Like her husband, she wanted to raise the visibility of the artists and their sometimes subtle, sometimes angry messages.

“She saw that [the collection] can be used as preparation to conduct political dialog now,” Sokolowski says, “the same way it was when it was forbidden and censored back then.”