Sabbuur “Saki” Ikhlas has held various titles over the past 30 years.

Teacher, coach, filmmaker.

But everything could’ve been different if he didn’t join the fencing team his sophomore year of high school.

For the rest of his life, he’d wonder—what if hadn’t? What if he’d gotten in that car instead?

He often thinks about that ride he never took. Not joining his friends the day they were stopped by police meant he would go on to win a state championship, earn a college scholarship and tell the story of why it all matters.

“It was fencing that saved me,” he says. “My life could’ve went a totally different direction.”

Ikhlas is the director of Untouchables: The Story of Coach Derrick Hoff and St. Benedict’s Fencing, a new documentary about the Newark high school’s remarkable coach and the team’s unprecedented rise to 10 undefeated seasons. The film, premiering this week as part of the Dances With Films Festival in New York, examines prejudice, racism, classism and how the school fencing program became a guiding light for vulnerable students.

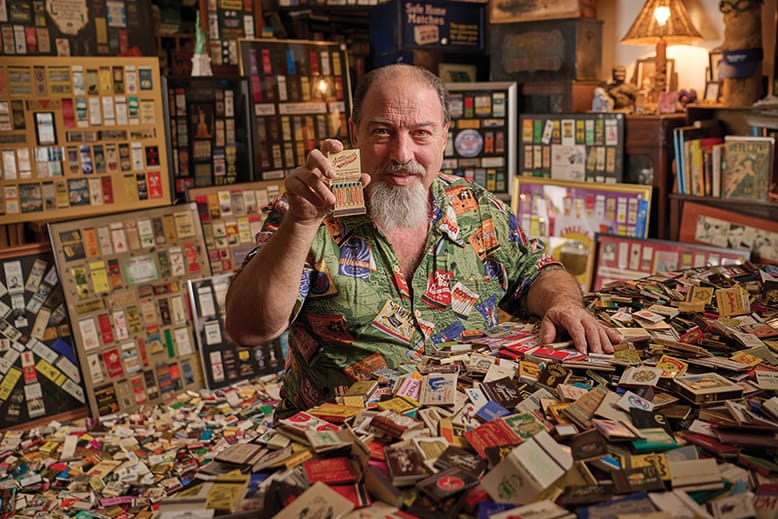

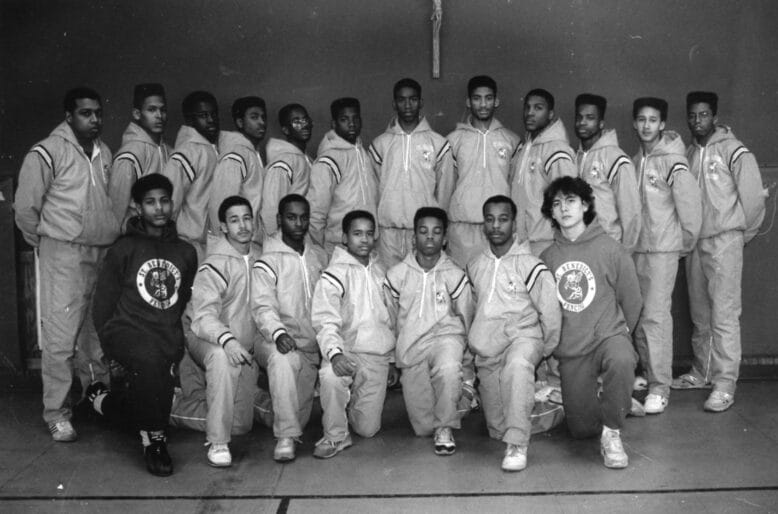

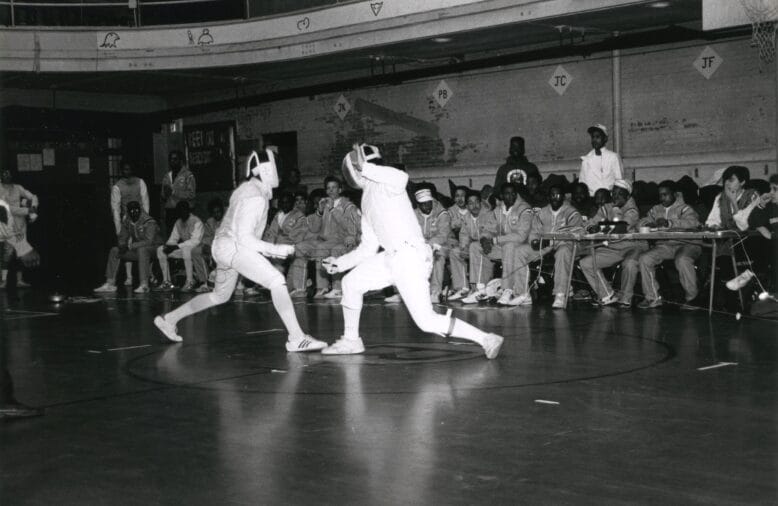

The 1990 Gray Bees fencing team, who won the first state championship in fencing for St. Benedict’s. Photo: Courtesy of Sabbuur “Saki” Ikhlas

About 36 years ago, Ikhlas had no idea that deciding not to get in the car with his friends would mean so much. He wouldn’t be there when police found a gun, and he wouldn’t be charged with a felony. Back then, fencing just demanded so much of his time, focus and energy.

“I locked in,” Ikhlas tells New Jersey Monthly.

You had to if you were on the St. Benedict’s Prep fencing team.

Coach Derrick Hoff held practices that could last four hours and end at 8 pm, with grueling conditioning and drills. Members of the team hustled so much they even practiced on Thanksgiving.

Hoff ran the St. Benedict’s Gray Bees fencing program from 1985 to 2000. Under his leadership, the team brought home its first state championship and dominated the prestigious Cetrulo Tournament. The team’s ’90s run was glorious, its achievement undeniable. But those wins arrived in an environment that tried to dim that shining triumph. Ikhlas says the feeling continues to this day.

“The state of New Jersey, the fencing association, they don’t celebrate that,” he says. “Nobody knows about this story except for us … It’s almost as if they want this to be a story to just die quietly with us.”

Coach Derrick Hoff in the Untouchables documentary. Photo: Courtesy of Sabbuur “Saki” Ikhlas

Looking back on those 10 undefeated seasons more than 25 years later, Hoff knows the truth: “It’s one of the best kept secrets ever in New Jersey athletics.”

Coach, Brother, Father, Protector

Derrick Hoff built the St. Benedict’s fencing team from decidedly modest beginnings.

As Hoff puts it, “10 wooden sticks.” That’s what he was given. Because of limited funds and resources, his wife ended up buying the team real equipment.

He came to St. Benedict’s after his cousin told the school about his fencing background. The Rev. Edwin Leahy, aka “Father Ed,” the Catholic school’s longtime headmaster, met Hoff and brought him on as coach.

Hoff knew, better than most, what fencing could do.

As a child, the sport served as a lifeline and escape from his father’s alcoholism and strain in his parents’ relationship.

“It wasn’t the most loving and nurturing environment,” he tells New Jersey Monthly.

The coach, originally from Detroit, had moved to East Orange with his family in 1964. He discovered fencing when he was 9 years old at Our Lady of All Souls School through his Belarusian gym teacher, who had fenced for the Soviet Army. The teacher convinced his parents that if he spent an hour practicing after school every day, he could become a formidable fencer.

St. Benedict’s fencing in action, circa 1989 or 1990. Photo: Courtesy of Sabbuur “Saki” Ikhlas

He continued fencing at Essex Catholic High School in Newark, home to fencing great Peter Westbrook, who became the first African American and Asian American fencer to win an Olympic medal in 1984. (Westbrook, who died in 2024, created the Peter Westbrook Foundation, which provides fencing training to children from underserved and underrepresented communities in New York.) Hoff went on to have a successful fencing career at Seton Hall University before coaching at St. Benedict’s, where he also worked as an admissions specialist.

Newark had once been a fencing powerhouse, in keeping with the tradition of Dr. Gerald Cetrulo, the highly influential fencing coach at Barrington High School who also built the fencing program at Seton Hall in the late 1930s. A Newark League included 10 teams from different city high schools. But by the early ’80s, no fencing programs remained, Hoff says.

As he built the St. Benedict’s fencing club into a team in the mid and late ’80s, he called his students “young warriors.” He asked them to commit fully to the sport, more than anything they’d committed to before. The goal: college scholarships. Recruiters would come to their tournaments, and Ikhlas received offers from St. John’s University, Drew University, The University of Chicago and Ohio State before choosing Rutgers.

St. Benedict’s made fencing, crew and water polo available to many students of color when students in the larger community did not have that access. At the school, sports were seen both as a path to college opportunity and a part of the educational approach. Father Ed cared about addressing what kids were facing at home and in the streets. The school motto is “whatever hurts my brother hurts me.” (St. Benedict’s was an all-boys school during Hoff’s time there and for most of its 158-year history.) As Leahy tells Ikhlas in the film, fencing helped build the kind of community that fostered strong relationships and accountability among teammates.

In order to draw intense focus from students, Hoff believed it was necessary to share his real, imperfect self with them—that was the key to building trust. And he wanted the fencers to trust him when he told them that regardless of what they had heard before, they could be winners.

“He was a Swiss knife role model, meaning whatever you needed him to be in your life, that’s what he was,” says Ikhlas, a former captain of the Gray Bees fencing team. “If you needed a mentor, he was a mentor. If you needed a father, father. Uncle, uncle. Brother, brother. Protector, protector. He was all those things to all of those kids for all of those years.”

In the film, Ikhlas interviews a series of fellow St. Benedict’s alumni. They recall childhoods in Newark and surrounding areas filled with cookouts, parades, block parties and friends. But the potential for trouble was also a dangerous reality of daily life.

“The mothers would call me,” says Hoff, now 64. He remembers one telling him that their son was “on the corner with the drug dealers.”

“I can’t tell you how many times I had to go and pull him off the corner and tell the drug dealer ‘leave this one alone. This one belongs to me.’”

Hoff says he tracked one student down before he could steal a car (he wanted to lift the vehicle to help his mother and brother, who had a disability). Single moms would call Hoff to say their sons didn’t come home, and when they showed up at school the next day, he would deal with them like he was their father: “Don’t you ever do that to your mother again.”

Former Gray Bees talk about how fencing allowed them to evade gang recruitment and channel rage into focus. Some were survivors of sexual abuse. Some lived with foster parents, or had a tough home life for other reasons, like parents who dealt with substance abuse. Hoff saw himself in those kids.

“I found that what I had experienced in my home, many of them were going through the same thing, and I just found that I felt I was obligated to try to bring some type of stability in the midst of all this confusion and madness that’s going on when they go home,” he says.

Hoff knew the loneliness of that experience. Fencing, he told students, could help them start to break the cycle and recreate themselves.

“You can be different,” he would say. “You have a choice, but you’re gonna have to work at it.”

Racism, Money and Defying Expectations

Fencing isn’t cheap.

Factor in equipment, travel to tournaments and entry fees, and a player could spend as much as $30,000 to $50,000.

“I knew I couldn’t afford to go to the Olympics, even if I was good enough. It just wasn’t happening, not where I was,” says Ikhlas, who grew up in Newark’s South Ward. “But we had guys that were that good. Their economic status would only take them but so far in the sport.”

Hoff and his wife often covered tournament fees for team members who couldn’t afford them. Hoff and Leahy got Continental Airlines to cover the team’s airfare to the Junior Olympics.

“It’s not about winning and losing,” Hoff says, reflecting on the team’s victorious run. “It was more like a social experiment—that, you know what, we’re all equal, even though this type of activity is reserved for the blue bloods. If you share it with the masses, we’re all the same.”

St. Benedict’s first won the New Jersey state championship in foil fencing in 1989. But fencing also includes two other weapons: the sabre and the epee. The team’s win in 1990 was its first overall championship victory spanning competition in all three weapons, making the fencing community take notice of what was going on at St. Benedict’s. It was the year they became the “Untouchables”—fencers who often literally couldn’t be touched during bouts—and a force to be recognized.

They were so successful at the Cetrulo Tournament in the ’90s, winning eight times when Hoff was coach, that he once got in trouble for not returning the trophy because he was convinced of another win.

“It was almost as if he knew we were creating history and he wouldn’t let us sway from that,” Ikhlas says of Hoff. “Everybody bought into the theology of what Coach was preaching, and I think that’s what made it work.”

“He was creating a fraternity,” Ikhlas says. While most of the team’s fencers were Black, the spirit of the team made every fencer — Black, white, Asian — see each other as brothers, he says.

“There was hazing. It wasn’t necessarily politically correct … But it was a brotherhood in the truest sense of the word.”

In the documentary, he explores the response of largely white, suburban fencing programs to the success of St. Benedict’s and its largely Black team. As the Gray Bees proved their skill on the fencing strip, they became the target of racist comments in a sport where people often expected contenders to be white. The St. Benedict’s athletes were accused of stealing equipment. The more they defied expectations, the more the powers that be seemingly wanted to punish them for doing so.

Coach Derrick Hoff with alumni of the St. Benedict’s fencing team who were interviewed for the Untouchables documentary. Director Sabbuur “Saki” Ikhlas, a former team captain, is at far left (in yellow/gold). Photo: Courtesy of Sabbuur “Saki” Ikhlas

After the fencing team won its first state championship, Hoff received a letter from the New Jersey State Interscholastic Athletic Association alleging that St. Benedict’s had cheated and violated rules, citing complaints from unnamed coaches. Some schools refused to fence the Gray Bees. Hoff remembers what the athletic director of Columbia High School in Maplewood told him about why their students wouldn’t be entering bouts with his:

“It’s not good for our kids to lose to your kids.”

“I will never forget that on the lives of my grandchildren,” Hoff says.

He recalls thinking “so this is what we do in Jersey? OK, no problem. I’m still going to coach.”

“It wears you down emotionally,” Hoff says of the bias he experienced, whether that meant dealing with other schools or having to make challenges to referee calls. And the Gray Bees?

“They saw it and they felt it,” Hoff says.

Untouchables uses animation to depict Ikhlas’ decisive bout for the 1990 state championship. He remembers the intensity of the moment.

“I just looked down at the end of the strip and I just saw all these people cheering against me,” he says. It threw off his concentration, but not enough to prevent him from winning. At the sign of victory, the team jumped into a pile to celebrate. Hoff was so overwhelmed he had to walk outside.

“We were the villains in everybody’s story, for whatever reason,” Ikhlas says. “We didn’t know why. But we were the heroes in our story.”

A Movie in the Making

Though some high school teams wouldn’t face St. Benedict’s, the team fenced exhibition matches against college teams and won.

“If we were a college team, we’d be easily top five in the country,” Ikhlas says.

After fencing at Rutgers, where he majored in English and Africana Studies, he returned to St. Benedict’s to teach English and coach the Gray Bees’ epee team.

“By the end of practice, I was exhausted every day,” he says. Working alongside Hoff, it was the first time he comprehended just how much labor his high school coach put into the job. It was during those years, still in the ’90s, that Ikhlas first told him that a movie could be made about St. Benedict’s golden age of fencing.

Later moving to Atlanta, then Los Angeles, he wouldn’t revisit that idea until he started working in film in the 2010s. It was always in the back of his head. In 2018, the director, also known as Saki Bomb, asked Hoff for his blessing and started crowdfunding. Ikhlas raised $5,000, which wasn’t nearly enough for the story he intended to tell. So he came up with the idea for a documentary to generate interest in a feature film treatment.

Making Untouchables took seven years. In 2020, St. Benedict’s alum Matthew Brewster joined as a producer. Ikhlas had been the Glen Ridge student’s English teacher in 1997 before he became his fencing coach. They got to talking again at a team reunion in 2018, and Brewster, a TV editor who worked with motion graphics, offered to help.

“Why isn’t this an Oscar-worthy story?” says Brewster, 42, who lives in New York. “We always had that as our standard … We really want Coach Hoff to be a household name.”

Ikhlas, who currently splits his time between Atlanta and Newark, is still committed to making a scripted narrative about St. Benedict’s fencing.

“I can see this as a series and I could see this as a movie,” he says. His vision: The Wire meets Friday Night Lights.

St. Benedict’s hasn’t won the Cetrulo Tournament since 2001, the year after Hoff left. “It still felt like his team,” Brewster says, remembering how the Gray Bees would maintain his standard during practices (team captains kept in close contact with their old coach).

The high-pressure years had taken a toll on Hoff, who decided to leave St. Benedict’s to support his family with a better-paying job. He started coaching fencing at Oak Knoll School of the Holy Child, an all-girls school in Summit. In 2002, he led the school’s team to a state championship.

Since 2001, he’s been a principal at Paterson public schools. The superintendent walked in when he interviewed for the position.

“I know who you are,” he said.

“That’s how I got the job,” Hoff says — his future boss was eager for the winning coach to share his story with students.

As for the Gray Bees fencing graduates, they represent many careers—professor, firefighter, college dean and more.

“I don’t care what happens when you leave St. Benedict’s,” Hoff would tell them. “The one thing that nobody can ever deny you is at some point in time in your high school career, you were a champion. You were the best. And you need to remember that as you go out here and pursue whatever endeavor, whatever career, whatever it is that you’re going to do. Remember that there’s championship creed in you.”

Brewster will never forget Hoff’s message about sweat equity — “If your shirt is dry at the end of practice, you didn’t work hard enough today.”

“That one has always carried me through,” he says.

When they were filming the documentary, Hoff watched as the boys he knew fell into a familiar rhythm with each other after years apart. “It was as if they never missed a day,” he says. “They were right back in high school, choppin’ it up, roasting each other … They reverted back to being kids in the locker room.”

That core relationship hasn’t changed, Ikhlas says — they’re a team, and Hoff’s their coach.

“Whenever we get around him, it’s like we’re 16 again.”

Untouchables: The Story of Coach Derrick Hoff and St. Benedict’s Fencing premieres as part of the Dances With Films Festival Saturday, January 17 at 12:15 pm at Regal Union Square (850 Broadway, New York). Click here to purchase tickets.