In 2007, Mike Gulotta was a man with 110 acres of Hunterdon County cornfield and a vision: to build New Jersey’s premier standardbred breeding operation and lead harness racing’s renaissance in the state.

The sport had taken a nosedive in recent years. Gulotta, former chief actuary for AT&T, and his partners had just bought the Flemington property for $950,000 in a public auction; it was a steal. He would break ground in early 2008 amid some of the worst economic conditions imaginable.

Gulotta knew the harness-racing industry in New Jersey was in shambles. But where others saw disaster, Gulotta saw opportunity. Besides, he was feeling lucky. He had just retired his champion stallion, Lis Mara, whose winnings totaled more than $2 million. The handsome bay pacer’s breeding syndication shares brought in another $2 million. It was all the capital Gulotta and his partners needed to transform the new property into Deo Volente Farms, a sleek, state-of-the-art breeding operation.

“Lis Mara produced all this cash flow,” says Gulotta. “He built this farm.”

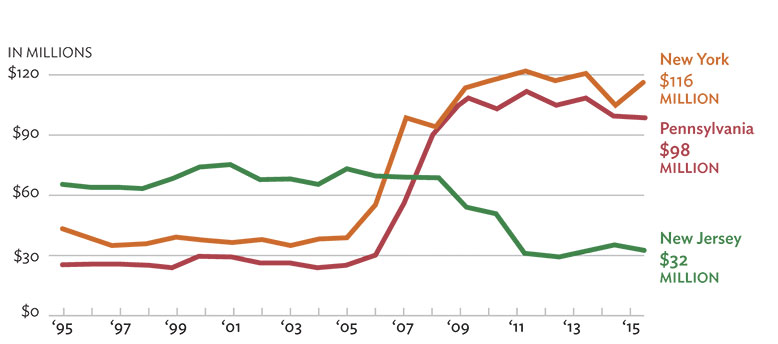

But Gulotta’s hot streak was up against some cold, hard facts. Purse money at the Meadowlands Racetrack and Freehold Raceway, New Jersey’s two standardbred racetracks, had decreased from a high of $75.4 million in 2001 to $68 million in 2008. Only 15 stallions were registered for breeding in the state that year, compared to 30 in 2000, according to the Standardbred Breeders and Owners Association of New Jersey (SBOANJ). The number of mares bred had slipped, too, from 2,274 in 2000 to 1,360 in 2008.

In retrospect, the numbers in 2008 seem rosy. By 2015, purse money had sunk to $32 million, just nine stallions stood for stud, and only 259 mares were bred. These key indicators of industry health look even more anemic when compared to neighboring states. Pennsylvania offered $98.6 million in purses among three tracks in 2015; New York had $116.6 million available among seven tracks. Pennsylvania had 45 stallions up for stud; New York stood 43.

This year, however, Gulotta and his fellow New Jersey breeders have reason for hope, thanks to the casino-gambling referendum that will appear on the state’s November ballot. Voters here will be asked whether they want to see casino gambling expanded outside of Atlantic City, which has had a monopoly on the industry since 1976. The outcome will have significant consequences for the state’s racing industry. (New Jersey has both standardbred, or harness, racing and thoroughbred racing. The thoroughbred industry is smaller, but is experiencing much the same contraction as the standardbred business.)

The proposed constitutional amendment would put two casino licenses up for bid in two different counties; each must be at least 72 miles away from Atlantic City. Bidding is restricted to principal owners in an existing Atlantic City casino for the first 60 days, and bidders must pledge at least $1 billion for the project. Though 50 percent of the tax revenue from the two casinos will go to “the recovery, stabilization, or improvement” of Atlantic City, a small piece of this new revenue—“no less than” 2 percent—will be dedicated to the horse-racing industry.

The amendment is stirring up substantial controversy, as reflected by several media campaigns, pro and con. Most of the opposition comes from interested parties in South Jersey who, despite the potential revenues earmarked for Atlantic City, believe two North Jersey casinos would be bad news for the state’s existing gaming operations.

But while attention to the amendment is mostly from casino interests, the November vote could also dictate the fate of the state’s racing industry.

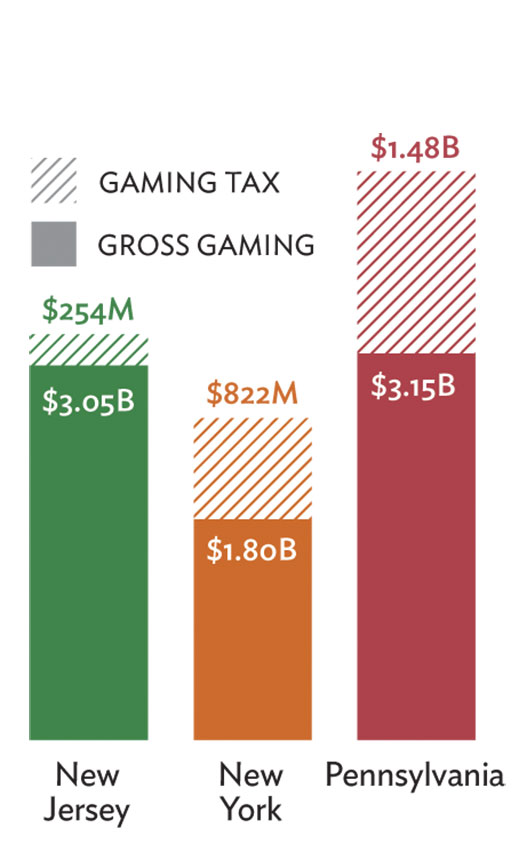

Area Gaming Revenue, 2013

“If we don’t get approval in November, it’ll be a disaster,” says industry veteran Anthony Perretti, director of the SBOANJ and owner/operator of Anthony Perretti Farm & Bloodstock in Cream Ridge. “It could be the finish of New Jersey standardbred racing.”

Perretti is the former general manager at Perretti Farms, also in Cream Ridge. The farm—once New Jersey’s largest horse-breeding operation—was founded in 1986 by Perretti’s father, William J. Perretti. At its peak in 2010, the farm had 6 stallions up for stud and 400 horses in all at the end of the birthing season. That ended in 2011, when Perretti sold his broodmares and put the Monmouth County farm up for sale. Shrinking purses and the inability to compete with Pennsylvania and New York breeders, who get tax revenue from their states’ casinos, drove his decision.

“A farmer growing a crop has a certain price point that [he can’t go below] to be economically viable,” says Perretti. “Likewise, raising equine has been extremely difficult, not being able to compete with Pennsylvania and New York.”

The industry’s suffocation by neighboring states has broader consequences for New Jersey’s economy. According to a 2007 Rutgers Equine Science Center study, New Jersey’s equine industry had a $1.1 billion annual economic impact and created 13,000 jobs. Roughly $780 million of that was from thoroughbred and standardbred racing-related operations and racetracks, which generated 7,000 jobs. In addition, the racing industry provided $110 million in federal, state and local taxes each year. The numbers have diminished since the study and would likely go into a steeper decline should the referendum fail.

Meanwhile, racing and gaming in Pennsylvania and New York have flourished. Pennsylvania has opened 12 casinos since 2007, and six of those are “racinos”—a combined casino and racetrack (standardbred or thoroughbred). New York operates 20 casinos, including nine racinos. A majority of the tax revenue allocated to the racing industry in those states supplements purse money. That has been a key factor in drawing top horses away from New Jersey tracks.

New York casinos have a graduated effective tax rate that starts at 60 percent; the racing industry gets 13 percent of the tax revenue. In Pennsylvania, the tax is 55 percent, with 12 percent going to the Pennsylvania Race Horse Development Fund.

In contrast, Atlantic City casinos pay a tax of 9.25 percent—and none of the revenue goes to the horse-racing industry. Racing received a short-lived purse supplement during the administration of former governor Jon Corzine—a total of $90 million between 2007 and 2010 to thoroughbreds and standardbreds. Governor Chris Christie, who took office in 2010, has focused on revitalizing Atlantic City. In a July 2010 article, the Star Ledger reported that Christie “declared the state government’s long romance with horse racing dead.”

The November referendum—if it passes—will amend the state constitution to allow the construction of two new casinos, but details such as the tax rate the casinos would pay will be hammered out in enabling legislation. Many suspect it will be at least 50 percent.

“It could very well be 50 percent,” said Assemblyman Ron Dancer (R-Cream Ridge), son of Harness Racing Hall of Fame driver Stanley Dancer. “There’s no doubt in my mind…that it will be significantly higher than the current 9 percent.”

Though the amendment guarantees that “no less than” 2 percent of the new tax revenue will go to the racing industry, many horsemen are not satisfied with that number. The money is desperately needed to enhance purses, which have decreased almost every year since 2000. However, 2 percent is paltry compared to New York and Pennsylvania—and it must be split between thoroughbreds and standardbreds.

Enabling legislation could set a higher percentage. Among those who will push for a higher rate are the SBOANJ, the industry’s advocacy group and stallion registrar, and TrotPAC, the industry’s political action committee.

“Two percent? Don’t worry about that,” says Gulotta, who last year lobbied 25 state senators for their commitment to support the racing industry.

“Generally they’re pretty receptive,” he says. “We’re trying to generate tax revenues, increase jobs, and we’re trying to preserve open space. What’s wrong with any one of those things?”

An undetermined percentage of the racing industry’s share of the revenue will go to the New Jersey Sire Stakes, a program established in 1971 that offers purses to winning standardbreds sired by SBOANJ-registered New Jersey stallions. Unsurprisingly, similar pools in New York and Pennsylvania dwarf New Jersey’s Sire Stakes pool. In 2015, New Jersey could offer only $2.4 million in state-restricted race purses. New York had $13.7 million up for grabs, and Pennsylvania offered a whopping $16 million to Pennsylvania-bred horses.

“If the Sire Stakes got enough money in the program,” says Perretti, “the people with stallions and mares will be coming back to the state. I mean, right now it’s disastrous what we’re dealing with.”

The dire financial state of the Sire Stakes is the reason the owners of Hanover Shoe Farms shut down their New Jersey satellite farm. Hanover Shoe Farms sits on nearly 2,500 acres in Hanover, Pennsylvania, and houses close to 1,000 horses. The operation maintained a satellite farm in Lambertville until December 2011. However, as the Sire Stakes purses shrank, the costs of operating in Lambertville outweighed the benefits of breeding New Jersey-eligible foals.

Purse Money at Racetracks, 1993-2015

“At one point it was lucrative to have New Jersey Sire Stakes horses,” says Patti Murphy, assistant manager at Hanover Shoe Farms. She says the economics can still change. “We would probably breed to the stallions if there were good stallions in New Jersey.”

In fact, more stallions are expected to come to New Jersey if the referendum is passed. Already, Rock N Roll Heaven, the 2010 Horse of the Year, was moved by his owner to Deo Volente Farms to stand at stud after spending the past four years at Blue Chip Farms in New York. “The owner said to me, ‘I want him to go to New Jersey because I think something good is going to happen in New Jersey,’” says Gulotta.

Gulotta is doing all he can to make sure the stallions keep coming. As chairman of the SBOANJ Breeder’s Committee, Gulotta was instrumental in the creation of the Breeder’s Incentive Program, designed to boost breeding to New Jersey stallions. For the 2016 breeding season, those who breed to a New Jersey stallion will receive a 25 percent rebate of the stud fee up to $1,500 after the foal is born. Gulotta says the program was founded on faith that November’s referendum will pass.

“The money’s not coming from the casinos or video gaming yet—it’s going to—but people tend not to act on what’s going to happen. So we have this program to incentivize,” explains Gulotta. “Once the referendum is passed, we’ll need it less. It’s like a bridge that we’ve created. It can be viewed as foundational. It can be built upon to put New Jersey in a more competitive position.”

For now, the racing industry can only speculate about how much annual revenue two casinos in northern New Jersey would generate. “I’ve had ranges anywhere from $10 million to $15 million that could potentially be available for distribution,” says Assemblyman Dancer. Such speculation is based on combined revenue for the two casinos of $1 billion per year and not less than 2 percent of the new tax revenue going to horse racing. That speculation is in line with the state Senate Minority Office’s revenue projection for the would-be casinos of $600 million to $1.5 billion per year.

Since the amendment requires bidders to pledge at least $1 billion, the two new casinos can be expected to look more like Atlantic City’s extravagant Borgata casino and spa rather than a small racino with a handful of slot machines. Borgata, Atlantic City’s most successful casino by far, raked in $696 million in 2015.

But would $10 million to $15 million be enough to turn around the horse-racing industry?

Perretti estimates the industry needs more like $60 million to $100 million. That would increase the size of New Jersey purses, which in turn would increase the number of race days and make the state more attractive to breeders.

Should the amendment be approved in November, it will likely be several years before the effects are felt by the harness-racing industry. By then, the industry will likely look different than in past decades.

“The mom-and-pops, where they have half a dozen mares and stuff, those operations aren’t around anymore,” says Perretti.

It’s unlikely those small farms will ever come back, predicts Gulotta. In that scenario, his Deo Volente Farms would be a big winner.

“If the referendum passes, forget it,” says Gulotta. “Everyone’s going to want to bring their stallion to New Jersey, and where are they going to go?”

Gulotta’s answer: Deo Volente Farms. But it all hinges on November 8.

New Jersey native Katie Greifeld is a reporter based in New York City.