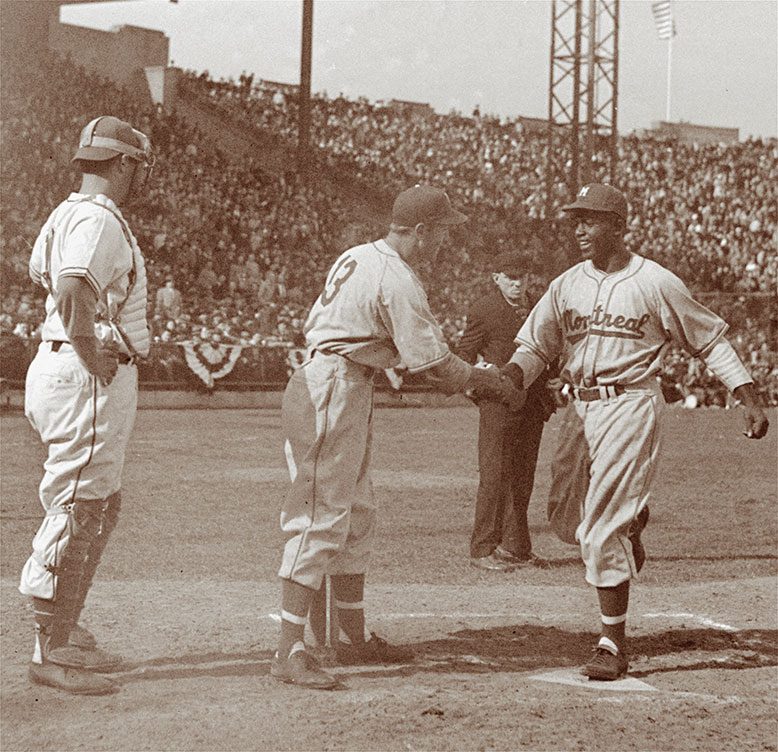

Jackie Robinson’s professional baseball debut, for the Montreal Royals against the Jersey City Giants, in Jersey City’s Roosevelt Stadium, is probably the most written-about minor-league game in history. It was certainly among the best attended: 51,873 fans saw Robinson usher in the integrated era of professional baseball on April 18, 1946.

Brooklyn Dodgers president Branch Rickey handpicked Robinson, UCLA’s first four-letter athlete and a veteran of the Negro Leagues and the U.S. Army, to smash professional baseball’s color line. He chose Montreal for Robinson’s minor-league apprenticeship to avoid this country’s racial baggage.

“The Southerners on the team didn’t like it very much,” recalls Robinson’s Royals teammate, pitcher Steve Nagy, a native of Franklin Borough in Sussex County and a Seton Hall graduate. “There was grumbling, but no real strife.” Nagy, now 96, amassed a 17-4 record in 1946. He remembers traveling north from spring training. “They wouldn’t let Jackie in hotels, and the team had to find him lodgings with local families. He didn’t like it, but he knew it had to be.”

Jersey City mayor Frank Hague, never shy about embracing the bread-and-circuses approach to governing, oversold the stadium (which seated about 24,500) and distributed tickets to the Democratic faithful. Lou Perrone, a Jersey City native, now 97, got on the distribution list because he was a high school football announcer (earning $3 a game). Scoffing at the suggestion that the crowd was merely standing room only, Perrone recollects, “we were sitting on top of each other in the aisles. The place was noisy, wild—and there was tremendous applause for Jackie every time he got up. There were a few scattered boos and even some racial slurs, but almost everybody there knew we were watching history.”

Batting second, Robinson grounded out to short in his first at bat. In the third inning, he whacked the ball some 340 feet over the left-field fence for a three-run homer.

The Giants’ third baseman was Larry Miggins, now 90. “I gave him two hits that day,” Miggins declares. “None of us had seen Jackie play, but Bruno Betzel, our manager, watched batting practice and decided Jackie was a strong pull hitter. He told me to play back for him, so when he bunted to me—twice!—he beat the throw, even though I could throw the ball through a brick wall in those days.”

After the first bunt single, in the fifth inning, Robinson stole second, brazenly advanced to third on a groundout to Miggins, then danced back and forth along the baseline, faked a steal of home, and forced Giants pitcher Phil Oates to balk, sending him home. In the eighth, after the second bunt, Robinson went to third on an infield out and again provoked a balk, by reliever Hub Andrews, for another run. “We never saw that kind of baseball,” says Miggins. And he was right. White baseball hadn’t seen that style of play since the pre-1920s dead-ball era. In between the two bunts, in the seventh, Robinson singled to right, stole second and scored on a triple. In the field, he started a double play to kill a Giants rally.

The Royals won the game 14-1, the International League pennant, and the Little World Series, against the American Association Louisville Colonels. Robinson hit .349 to win the batting title. The following year, 1947, he was promoted to Brooklyn and broke the major league color line. He eventually went to the Hall of Fame and immortality. But it all began in Jersey City.

Nick Acocella is the editor and publisher of Politifax New Jersey and the author of a dozen books on baseball. He lives in Hoboken.