When Keaira Still was heading into her freshman year at Haddon Heights High School a decade ago, she was a bit apprehensive. After all, she was going to be one of the few new kids—a “lone ranger,” as she characterized it.

Keaira had spent the previous eight years at Holy Rosary, a Catholic school two towns over in Cherry Hill. “I had been wearing a uniform every day for those years. Here, it was everyone wearing jeans. It was all a little bit scary,” says Keaira, who had grown up in Lawnside, a feeder district for Haddon Heights High. Within just a few weeks, though, Keaira felt she had been at the high school her whole life.

“I found out 20 or 30 kids were related to me in some way,” she says. “That is what being a Still is all about. The family has been here so long and is so conscious of being a family that you never feel left out of anything.”

The first Still, known in the family’s oral history as the Guinean Prince, arrived in New Jersey in 1630 as an indentured servant. The history is fuzzy for a while after that but is generally tied to Maryland and New Jersey.

By the early 1800s, the Still family was firmly established in southern New Jersey, particularly in the area that became Lawnside, a hamlet neighboring Haddonfield. By 1840, Lawnside was established by abolitionists, mainly Quakers from Haddonfield and Philadelphia, who purchased the land to house free black families, among them the Stills.

Lawnside was incorporated in 1926; it is believed to be the first self-governing, overwhelmingly African-American town in the North. It remains 94 percent African-American and full of Stills—perhaps as many as 100 members of the extended family, including Keaira’s grandparents, Kenneth, a retired military lifer, and Gloria, a former English teacher. Another prominent Still is Kenneth’s brother, 80-year-old Clarence Still Sr., the founding president of the Lawnside Historical Society.

Every August, Clarence hosts the Still family reunion at his place, a former family farm next door to the borough’s biggest employer, the United Parcel Service center. This summer marked the 140th Still reunion—a daylong barbecue, church service, and general gossip-fest for several hundred Stills from as far away as Arizona.

“It’s just a general good time, nothing fancy. Lots of good food and lots of storytelling,” says Clarence, who spent 40 years working at the Budd Company manufacturing plant in Philadelphia. Every year there seems to be some surprise—a Still is rediscovered in Europe, or someone who was thought lost forever just shows up. “Stills are proud of being Stills, even if their name has been ‘Johnson’ for a couple generations. They show up sometimes just to say they are Stills.”

Some years there are as many as three Still family reunions in New Jersey. The Vineland branch of the Stills has a more church-based day in the fall and, off and on, there have been reunions of the Burlington County branch of the Stills in Medford or Mount Laurel. The Rev. Terrell Person gets invited to preach at all of them and, he says, it is never a burden. After all, he is at least the fourth generation of preaching Stills, going back to Dr. James Still, known as the “black doctor of the Pines,” the son of runaway slaves who came to Indian Mills in Burlington County. James Still’s brother, William, moved to Philadelphia as an adult and was instrumental in helping set up the Underground Railroad, which had stations in Lawnside. In 1871, James’s son, James Jr., became the third black male to graduate from the Harvard University School of Medicine.

The Stills have long valued education, says Keaira, who graduated from Dartmouth College last year and is currently teaching math in Philadelphia under the Teach for America program.

“There was no question I was going to college,” says Keaira, who was raised by her grandparents. “When you hear of our family’s history of firsts, you know that is what you are going to do. My aunt went to Vassar and a cousin went to Johns Hopkins, so I am certainly not the first to go to an Ivy-type school.”

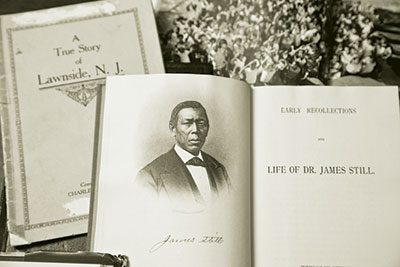

Stills also are conscious and respectful of their history. The Still Family Society, which meets monthly, has three Still family history books, The Early Recollections and Life of James Still; Kidnapped and Ransomed, the memoirs of the runaway slave Peter Still; and The Underground Rail Road, the memoirs of the nineteenth-century William Still.

Though there are Vineland Stills and Mount Laurel Stills and now a Stills diaspora around the country, most of the memories reside in Lawnside. In its heyday, from the 1920s through the 1960s, Lawnside was a center of entertainment, fun, and recreation for the local black community—and prominent visitors as well.

“There were barbecue pits on both sides of Evesham Road, which were especially busy on summer Saturdays,” says Clarence Still. Someone—maybe the county, maybe just enterprising residents—dammed up a portion of the Cooper River in the 1930s, making a lake that had paddleboats, rowboats, and swimming throughout the summer. Clubs along Evesham were the rage from the Depression through the 1960s.

“There was Pearl’s Celebrity Room and the Acorn and the Hi-Hat on the White Horse Pike. There was the Cotton Club and Dreamland and the Whippoorwill,” says Clarence. “It was partying and dancing and eating, and if a big celebrity was in Philadelphia—Sammy Davis Jr., Count Basie, Sarah Vaughan, Joe Louis—you could be sure he or she would come over during the day or after they were done performing.”

The Stills would be there, too. “We weren’t a family to miss a party,” he says. “And even if they lived elsewhere, they would come back to Lawnside.”

Lawnside is a quieter place now. “Mostly, it is just a bedroom community,” he says. But there are visits from young Stills like Keaira, who lives in Philadelphia but always remembers home and family.

“When I drive around Lawnside, I always see someone who is related to me, and I can almost guarantee the person I don’t know is something like my mother’s brother’s cousin’s daughter,” she says with a hearty laugh—also emblematic of all the Stills. “It’s one of those amazing feelings you should have in life, a place to go where you always have someone who is like you.”

Robert Strauss is a frequent contributor. He lives in Haddonfield.