The infant sperm whale lay on its side in the cold sand, sleek and shining in the December sun. Adult sperm whales can grow up to 67 feet and weigh as much as 45 tons. This one was tiny by comparison—weighing about a ton and, at 12 feet long, measuring roughly the size of a kayak. Authorities from the Marine Mammal Stranding Center (MMSC) in Brigantine noted that it was still nursing before it died and speculated that it might have gotten separated from its mother and starved to death.

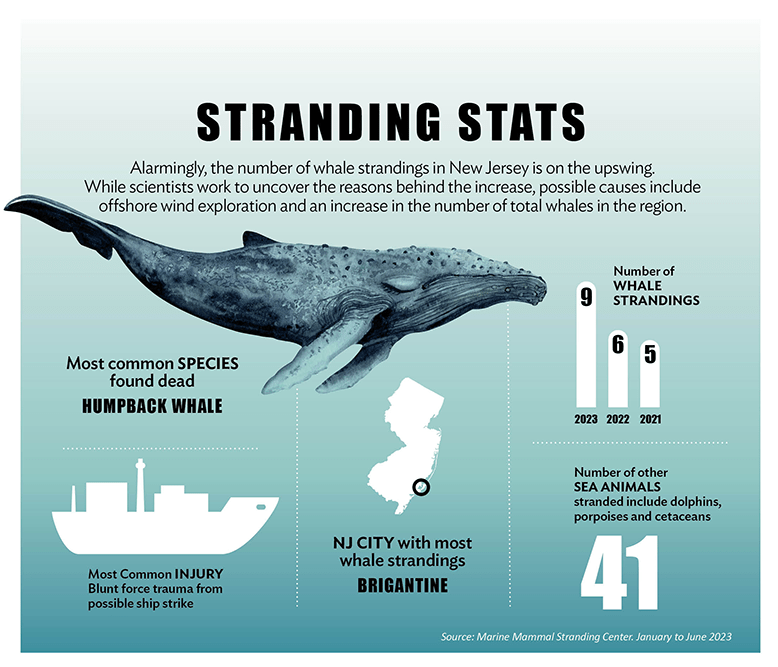

What made this whale particularly significant, though, wouldn’t become clear for several months. As it happens, it was the first of an alarming number of dead whales that washed up on, or were spotted near, East Coast beaches between December 2022 and March 2023—30 in all, 11 of them in New Jersey. (More than two dozen dolphins were also stranded in New Jersey during that time.) Of those 11 whales, 9 were humpbacks; the other two were a sperm whale and a pygmy sperm whale. In comparison, the average number of annual humpback strandings in the entire U.S. is between 6 and 22.

In fact, the number of whale strandings along the East Coast has increased markedly since 2016, a year before the federal National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) declared an unusual mortality event (UME)—defined as “a stranding that is unexpected; involves a significant die-off of any marine mammal population; and demands immediate response”—for humpback whales and North Atlantic right whales, an endangered species whose population has dropped to around 340. As of this writing, the East Coast has seen 200 humpback strandings and 98 strandings of right whales since the UMEs were announced.

Ever since environmental organizations raised the rallying cry “Save the Whales” in the late 1970s, the awe-inspiring marine mammals have become symbolic of the negative impact we humans have wrought on the natural world. So it should surprise no one that this latest surge in strandings has raised deep concern for the whales’ wellbeing and a clamor for a definitive explanation of their deaths. One potential cause has received more press recently than any other: the geotechnical and geophysical surveying of the seafloor in preparation for the construction of Ocean Wind I, 99 wind turbines to be built off the coast of Atlantic City by the Danish company Ørsted—the first wind farm authorized for New Jersey but likely not the last.

Illustration: Shutterstock

In our highly polarized era, it was almost inevitable that the issue would become politicized, with (mostly) Republicans pointing to the offshore wind exploration as a potential cause of the whale strandings and (mostly) Democrats rejecting that explanation as baseless. As calls for an explanation mount, the split down party and political lines isn’t likely to contribute positively to the search for clarity.

EXPLORATION

It was the fifth dead whale on New York and New Jersey beaches, a female humpback that washed up in Atlantic City, that sounded the alarm for Cindy Zipf, executive director of the Long Branch-based nonprofit Clean Ocean Action (COA). “It caused us concern enough to ask, ‘What is happening?’” she says. “We looked into what was different about this December and early January.” The only thing that she and Kari Martin, COA’s advocacy campaign manager, could point to, she says, was offshore wind exploration. “We looked at shipping, and shipping didn’t seem to be any different. The same fishermen were fishing. And the only thing we noticed were the number of IHAs that had been issued.”

IHAs—Incidental Harassment Authorizations—are allowances granted by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service under the Marine Mammal Protection Act, authorizing the incidental, but not intentional, harassment of a specified number of marine mammals for no longer than a year. What Martin found was that IHAs had been issued to 11 companies engaged in offshore wind exploration activities, allowing them to incidentally harm more than 63,800 marine mammals. (Since then, additional IHAs have been issued.) When a sixth dead whale washed up, again in Atlantic City, Zipf and Martin were moved to send a letter to President Biden demanding, among other things, an immediate investigation into the whale deaths in New York and New Jersey and a moratorium on offshore wind activity off the two states until an assessment of the cause of the deaths was determined.

No one is blaming the deaths on wind power itself or on the construction of wind farms, since that construction isn’t planned until 2024. Instead, critics have expressed fears that the sonar and other sounds used to map the ocean floor could be detrimental to whales, perhaps by frightening them or deafening them, both of which, they suggest, could lead to ship strikes or fishing gear entanglement—the two leading human-caused means of death in marine mammals. If so, that would be difficult to prove through a necropsy, since it would entail examining certain microscopic parts of the ear bones, which, according to Allison Ferreira, NOAA’s communications and internal affairs team supervisor, decompose within hours. “If a whale is already in moderate to advanced decomposition, as is often the case unless a whale is alive when first stranded,” she says, “then microscopic changes in the ears are no longer detectable.” Critics like COA also posit that an increased number of ships working in the area to survey the sea floor could be leading to an increase in ship strikes.

After the COA’s White House letter, additional demands for a moratorium and/or investigation followed. At the end of January, 12 mayors of Jersey Shore towns—Bay Head, Brigantine, Deal, Linwood, Long Beach Township, Mantoloking, Margate, North Wildwood, Point Pleasant Beach, Spring Lake, Stone Harbor, and Wildwood Crest—sent a letter to New Jersey members of Congress, urging them “to take action now to prevent future deaths from needlessly occurring on our shorelines.” A similar letter, this one calling for a moratorium on offshore wind exploration and signed by 30 New Jersey mayors, was sent to representatives Jeff Van Drew (R-NJ), Chris Smith (R-NJ), and Frank Pallone (D-NJ) in late February. On March 22, Van Drew introduced a congressional resolution demanding a moratorium on offshore wind development. And on March 30, Smith introduced an amendment calling for an independent investigation into the environmental review processes for East Coast offshore wind development, which lawmakers approved, 244 to 189.

Like Zipf and Martin, Van Drew believes that the timing is telling: “The dates [of the whale deaths] alone coincide with when they really started to do the research,” he says, referring to the surveying of the sea floor. That work began in January 2019, two years after the latest humpback and North Atlantic right whale UMEs were announced.

It should be noted that 26 of the 30 mayors and a town council member who’ve proposed a connection between whale strandings and offshore wind exploration, along with the two New Jersey congressmen who’ve done the same, are Republicans, and Republicans are far more likely than Democrats to oppose or criticize wind power. (A 2021 survey conducted by the Pew Research Center found that 91 percent of Democrats favored the creation of more wind farms, as opposed to 62 percent of Republicans, the latter figure down from 80 percent in 2016.) Certainly, Van Drew was a critic of offshore wind before he and others suggested a relationship between wind and whales. He admits that even if it were proved that there was no connection between the two, he’d still be loath to endorse wind power. “And that wasn’t always my opinion,” he says. “It has changed over time for sure.” Among reasons for that change he lists potential negative effects on fishing, tourism, and the environment.

At least one of the New Jersey-based environmental organizations calling for a moratorium on wind exploration, Protect Our Coast NJ, has been linked to the Caesar Rodney Institute, which has received funding from the fossil fuel industry. Ed Potosnak, executive director of the New Jersey chapter of the nonprofit League of Conservation Voters, says that the South Jersey politicians clamoring for a moratorium “are opposed to offshore wind possibly because it will obstruct their view. When you ask questions, in every instance—and we’ve been through this on many issues—the main connection is that they’re opposed to offshore wind at all costs.”

IF NOT WIND, WHAT?

Since the beginning of the year, when questions about offshore wind activity as a cause of whale strandings began to arise, government agencies—including NOAA and the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management—and many environmental groups have made the point, as Potosnak does, that “there is no evidence of a connection between the strandings and offshore wind, and there’s no evidence that wind exploration has caused the death of any marine mammal.” (In April, NOAA issued a report stating that offshore wind activity—not, specifically, offshore exploration—couldn’t kill or seriously harm marine mammals but might “adversely affect” them.)

What evidence of death we do have consists of necropsies conducted by the MMSC, who examine the whales on the beach and, when possible, send tissue samples off to be examined in a laboratory. One of the 11 whales that washed up recently on New Jersey beaches was too badly decomposed to be necropsied; two were only witnessed floating offshore; and one necropsy couldn’t be fully completed due to a coastal storm. Of the others, four showed evidence of ship strikes; further research may reveal whether the strikes occurred before or after death. More than half of all whales found dead on beaches, in fact, evidence no clear cause of death, either because decomposition is too advanced or because they may have died of an infection that isn’t easily detectable. As of this writing, no reports based on the tissue samples have been issued, and on its blog, MMSC notes that “final necropsy results can take several months to be returned.” (MMSC declined to be interviewed for this article, and while it didn’t offer an explanation, it’s possible that the organization has become media-shy after receiving threats from offshore wind opponents accusing the center—without evidence—of hiding the truth about the whale deaths and taking money from the offshore wind industry.)

One simple explanation for the increase in whale deaths may be the increase in whales. Research has shown that the number of humpback whales feeding off New Jersey and New York has burgeoned in recent years. A 2019 study published in the journal Marine Policy, for example, reported a substantial uptick in both humpback sightings and strandings in the area since 2011.

The humpbacks are likely following food—notably menhaden, an oily fish that makes up a substantial portion of their diet, along with herring and sand lance. Malin Pinsky, an associate professor in Rutgers’ department of Ecology, Evolution, and Natural Resources, notes that “warmer ocean waters, along with other factors, have been linked to more menhaden in our region.” Documentably cleaner waters may also be drawing the whales closer to shore.

Of course, it’s possible that at least some of the ship strikes evidenced in the recent strandings originated from vessels engaged in offshore wind exploration. But Potosnak believes that’s unlikely. He notes that every vessel involved in wind exploration is required by the federal government to have a Protected Species Observer (PSO) aboard. The PSOs, he explains, “listen with headphones to the water to hear if any whales are around, and visually, they’re looking constantly for evidence of whales. And if they find that evidence, they stop activity right away.”

Should a PSO miss whale activity, it’s not clear that sonar and other sounds generated during seafloor mapping would cause significant harm. Ferreira notes that “existing data indicate that the acoustic sources used during site assessment surveys do not have the potential to injure, seriously injure, or kill whales.” These low-frequency sounds differ from the seismic air guns often used during surveys for offshore oil and gas drilling, which have been shown to affect the feeding rates of sperm whales and breathing patterns in bowhead whales.

BACK AND FORTH

Despite the recent outcry, Governor Murphy has said several times that there will be no moratorium on offshore wind exploration. On February 22 his office responded to calls for such a moratorium by noting that “the results of investigations have been unanimous and unmistakable: at this time, there is no evidence of specific links between recent whale mortalities and ongoing surveys for offshore wind development.”

That hasn’t stopped calls for a moratorium or, in the case of a March 28 letter from four Democratic U.S. senators—including New Jersey’s Cory Booker and Robert Menendez—calling for more transparency from NOAA regarding its investigations into the whale deaths. Potosnak observes that we’ve already had a moratorium of sorts, during the period after NOAA noticed a spike in whale mortality in 2016 and before seafloor mapping began in 2019.

Amid the high-decibel back-and-forth about offshore wind, one important point is in danger of being drowned out, and that’s the predicted impact of ocean warming on marine life. “If folks are really interested in protecting our marine mammals,” Potosnak says, “then they need to understand that the greatest threat to them is climate change itself.”

Leslie Garisto Pfaff, a contributing writer to New Jersey Monthly, has had a longtime interest in the environment.

No one knows New Jersey like we do. Sign up for one of our free newsletters here. Want a print magazine mailed to you? Purchase an issue from our online store.