A week after George Floyd’s killing by a Minneapolis police officer in May 2020, Michelle Miller’s cell phone buzzed.

The CBS Saturday Morning cohost had covered other stories about violence and racial animus: the shootings of Michael Brown and Trayvon Martin, the mass murder in a Charleston, South Carolina, church, the Sandy Hook Elementary School massacre. Now, with the nation aflame over Floyd’s fate, a senior producer at CBS News’ weekday morning show—where Miller sometimes served as cohost— wanted her perspective.

The resulting television segment was more personal than anyone expected.

“I exposed why stories like that really resonated with me,” says Miller, who lives with her husband and children in South Orange. The contours of her childhood—indeed, of her entire life—had been etched by racism.

She had been abandoned by her mother, whose Mexican immigrant parents disapproved of her relationship with a Black man, a prominent surgeon and civil rights activist.

Michelle Miller says her husband, Marc H. Morial, has been asking her to write a book for 25 years.

In the television piece, Miller described herself as “the product of an interracial union that my father celebrated and my mother to this day does not acknowledge.”

After it aired, a tearful Miller added: “No one on that side of my family knows who I am, knows that I exist.”

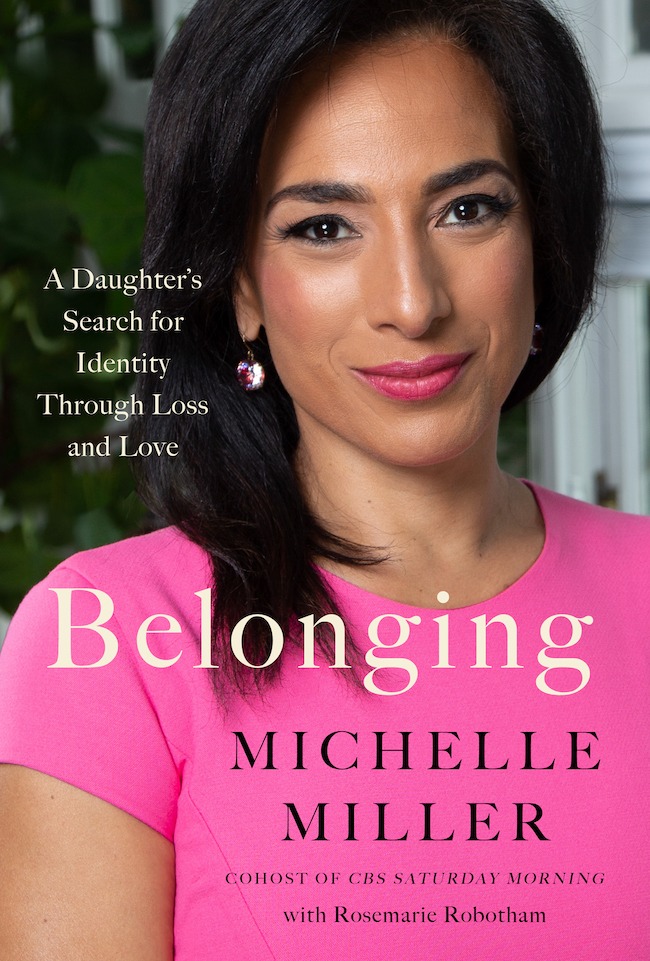

“The story lasted just minutes, but its impact on me was indelible,” says Lisa Sharkey, a former journalist who is senior vice president of creative development at HarperCollins Publishers. Sharkey encouraged the writing of Miller’s emotional new memoir, Belonging: A Daughter’s Search for Identity Through Loss and Love, published by Harper in March.

Working with cowriter Rosemarie Robotham, Miller artfully details her struggles with her motherless childhood and racial identity. The memoir also chronicles happier events: Miller’s rise through the broadcast-journalism ranks (she has won Emmy, Gracie, DuPont and Edward R. Murrow awards) and her marriage to Marc H. Morial, president and CEO of the National Urban League and former mayor of New Orleans.

But the book’s most powerful theme is Miller’s continuing efforts to find maternal surrogates and, finally, connect with her biological mother, the pseudonymous Laura Hernandez.

“My husband’s been asking me to write a book for 25 years,” Miller says.

She had promised her mother never to expose her. She also may have been afraid of the emotions the project would stir. “I sprint through life, and, for whatever reason, I am racing to take care of everything that I need to take care of,” Miller says. “It almost allows me this superhero ability not to feel in the moment.”

The book rips away that defense. It tells a complicated story of racial rejection and acceptance, and of Miller’s longing for a more conventional upbringing.

“I wanted the nuclear family—a mother and a father, this idyllic life,” she says.

Instead, Miller lived with her paternal grandmother, “Bigmama,” with her father making frequent visits. “Look, my story is not a story of tragedy. It’s not a story of a hard-knock life,” she says. “I grew up in South Central Los Angeles, but I did not want for anything because my dad was a physician, and my grandmother was an astute investor and businesswoman, outside of being a retired teacher. We had means. I was an entitled kid”—even a debutante—“growing up in the hood.”

Bused to predominantly white schools, she excelled academically but had trouble fitting in, sometimes feeling like a “racial imposter.” Multiracial by heritage, with a mix of European, Native American and African ancestry, she identifies as Black.

Belonging is filled with complex, vivid characters, including her late father, Dr. Ross Miller Jr. A brilliant Howard University graduate, he was the first doctor to minister to Robert F. Kennedy’s fatal wounds on the night of his 1968 assassination.

Miller would later tell that story on the air, too.

Michelle Miller with her happy brood, husband Marc H. Morial, center, their children and son-in-law. Photo: Courtesy of Randi Baird

The scion of a distinguished family that included a federal judge and a college president who was also an ambassador to Sweden, Miller’s father was staunchly supportive of his daughter, though worried, reasonably enough, about her choice of broadcast journalism as a career. He was also, the memoir says, “a charming rogue” who pursued overlapping, sometimes dishonest relationships with the many women who loved him. In his professional life, however, he remained “a great proponent for women,” Miller says.

The doctor and his first wife, Iris, had just adopted two little girls when Hernandez, with whom he was having an extramarital affair, got pregnant. When Iris discovered the situation, she retaliated by taking one of the girls—the darker skinned child— back to the adoption agency. No one in the family ever saw her again.

Ross continued to date Hernandez intermittently for years and offered to marry her. But because of her family’s opposition, she declined and asked him to stop bringing their daughter, a toddler who would cry nonstop when they said goodbye, to their meetings.

The couple later parted ways, and Ross would eventually divorce Iris and remarry.

Miller has no recollection of those early visits with her mother. She does remember that, when she was about nine, her father took her, without warning, to see Hernandez, who was about to marry and leave the country with her new husband. “That was not a good move,” says Miller.

The visit set up a clash between her father, angry at her mother’s neglect, and her mother, afraid of having her past exposed. The reunion ended abruptly.

Years later, when he was dying of cancer, Ross urged his daughter, then 22, to seek out her mother. As the memoir recounts, they had an emotional lunch during which Hernandez told her daughter that Ross Miller was, for years, “the love of my life.”

“There was wonder about being physically in the presence of this woman,” Miller recalls of their lunch. “But I didn’t feel a burning attachment to her. I didn’t feel that she had a burning attachment to me. I felt politely pleased that she met with me and that she answered my questions. I genuinely felt lighter in the moment. I thought, once she had met me, she would slowly begin to change her mind about having a relationship with me.”

That never happened, despite Miller’s attempts to keep in touch by phone. Hernandez, civil but emotionally detached, emerges from the memoir as a tragic figure, caught in the web of both America’s racism and her own mistakes.

“She was stuck in her loop. She was stuck in her lie,” Miller says.

In the end, her insistence that Hernandez acknowledge her publicly created a rift that continues to this day.

Among the lessons Miller says she has learned is, “You can long for things your whole life and not appreciate what is in front of you.” One of her deepest regrets involves her grandmother’s late-life caregiver, Vondela, who helped raise her after her grandmother’s death.

“When I lived with her those five years, we were thick as thieves, but when I left” to attend Howard University, “I did not give her what she needed,” including an invitation to her college graduation.

Miller says she remains open to reconciliation with her mother, who, in 2016, stopped answering her calls. The book is “a nudge for her to come out,” Miller says. “If there’s something so fundamental to who you are that you’re hiding, you can never be yourself. You’re always looking over your shoulder. I don’t know how you live with something like this.”

But Miller stresses that she wrote the book for herself, as well as “to pay homage to my father and my grandmother, and to knock down the stereotype that Black men don’t care for their family.

“The through line for me is that, despite this sense of longing, I always did belong,” Miller says. “You have to find belonging within yourself. Appreciate what you do have. Everything I lived through got me here—every mistake, every misunderstanding, every vulnerability. I hope that my life and my mistakes and my triumphs are a lesson to others.”

Julia M. Klein, a cultural reporter and critic in Philadelphia, has written for the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Washington Post, Mother Jones, Slate and other publications.

No one knows New Jersey like we do. Sign up for one of our free newsletters here. Want a print magazine mailed to you? Purchase an issue from our online store.