There are a lot of iconic towns here in the Garden State, each with its own allure. Asbury Park has the Boss and New Brunswick’s got the Big Ten. Trenton honors history, while Atlantic City’s all about sand and sin. The Devils are in Newark, the Great Falls in Paterson, and Bedminster lays claim to you-know-who.

But when it comes to having it all, to being a place where young professionals want to be, few places beat Hoboken—which is a real trip for me, because when I grew up there in the 1960s and early ’70s, everyone was intent on leaving.

Sinatra aside, these are boom times for the quirky place where I was born, where both my parents lived their entire lives, and where my grandparents planted the DePalma flag in the New World way back in 1909. But when I visit Hoboken now, I barely recognize the place I once knew as well as my Baltimore Catechism.

Hoboken’s Pier C Park. Photo: Laura Moss

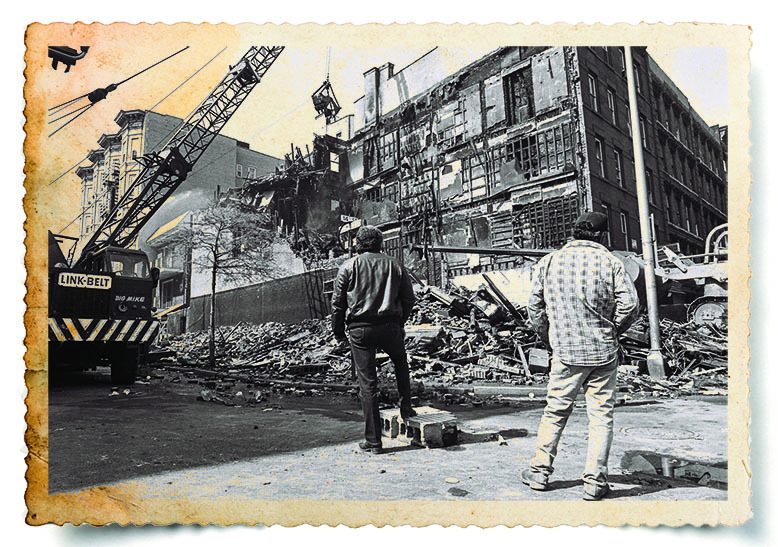

The pencil factory where my grandfather got his start is gone. So are the piers where my father worked, and the Italian-ice factory where I earned my first dime (literally, a dime) helping a guy named Tex push his wagon to a park a few blocks away. In place of the city I once knew is a dazzling array of chic condos, high-end restaurants and popular bars. The Hoboken waterfront that was imprisoned behind iron gates when I was a kid is now a stunning urban oasis with a view of the Manhattan skyline that even Manhattanites envy.

With its ferries, buses, light-rail and PATH trains to Manhattan, Hoboken so closely aligns with today’s walkable-suburbs ideal that it may soon be within striking distance of its all-time population high of 70,000—last reached back in 1910, when my grandparents lived in a cold-water flat on Willow Avenue jammed with relatives. Incredibly, a one-bedroom condo on that same crowded block recently sold for $542,000.

The Hoboken waterfront is a vibrant urban oasis for residents and visitors. Photo: Laura Moss

The old city is now young, with an average age of 32, which means that none of those people had even been born when the city went through the darkest periods of its long history. It can seem that the whole city has tried to simply forget the sorrowful cycle of destruction, displacement and rebirth that led to the new Hoboken.

But a few residents have recently challenged the city to own up to its past as thoroughly as it embraces its future, in the process opening old wounds and tearing new ones into the fabric of the community as it confronts how Hoboken got to be what it is today.

The Hudson Tea Buildings offer high-end, one-to-three-bedroom condos for $515,000-$3.9 million. Photo: Laura Moss

Here’s what we know: From 1978 to 1983, just as Hoboken’s transformation was taking off, ten suspicious fires left 56 people dead—many of them women and children, many of Puerto Rican and Guyanese descent. In 1992, a sensational film called Delivered Vacant offered a sinister narrative too sensational to pass up, claiming the fires had been set by greedy landlords to push out old tenants and bring in new ones who were younger, richer and whiter. Local newspapers weighed in with sensational headlines like “Hell on 14th St.” after a deadly 1982 fire at the Pinter Hotel in the city’s north end killed 12 people.

That newspaper clipping is one of many included in a multimedia exhibition that runs until the end of the year at the Hoboken Historical Museum, which, since 1986, has lovingly uncovered and preserved a record of what the city and its people were like before gentrification. But it has never addressed gentrification itself until now. With powerful photographs, artifacts and recorded interviews with fire survivors, the exhibition outlines in grim detail a campaign of terror that altered the city forever.

But is it an accurate accounting of what took place?

The guest curator of the exhibit is North Jersey resident Christopher López, a 38-year-old photographer who works in documentary histories. In 2021, quarantined by Covid-19, López was doing internet research for a project. “I had the topic of gentrification on my mind, so I Googled the definition,” he says. Having lived for a time in the Bronx, he was familiar with gentrification in New York. He didn’t know Hoboken well, but he knew the city had changed.

He returned to Google and this time found a provocative academic article in the Journal of American History titled “Hoboken Is Burning: Yuppies, Arson and Displacement in the Postindustrial City.” That led him to newspaper accounts of the fires, but something didn’t seem right. “I became kind of angry about some of the things that I was reading. People casting the blame on tenants, you know, things like kids playing with matches and lovers’ quarrels, things like that,” he says.

The articles quoted the mayor, fire chief, county prosecutor and other officials, laying out theories about how the fires had started, but López didn’t believe any of it, saying, “It’s not a cosmic coincidence that the city is burning and changing at the same time.”

In June 2022, López and the museum received a grant from the NJ Council for the Humanities. Earlier this year, “The Fires: Hoboken 1978-1982” opened. It is a damning presentation that accuses Hoboken landlords of committing arson for profit.

Robert Foster is the executive director of the Hoboken Historical Museum. Photo: Laura Moss

Robert Foster, the museum’s executive director, says that, for some people who lived through the fires, talking about such a bleak period has been a kind of catharsis, while for those new to Hoboken, it was a sobering discovery. “But a few people,” Foster says, “have asked, ‘Why are you doing this?’”

In the decades since the fires, there’s never been a comprehensive accounting of what happened. In the absence of an official record, the most aggrieved members of the community have devised their own. Survivors told López their emotional recollections of the tragic fires and claimed that officials were covering up the arsons to protect the city’s image.

Their feelings are legitimate, their tragedies real. But as a journalist for more than 50 years, I know how complicated history can be. I try always to remember that feelings aren’t facts, the truth is not negotiable, and questions like “what else could it be?” can have many answers, or none at all.

The record shows that the local fire and police departments, backed by federal and state agencies, did investigate the fatal fires. Two in particular caught their attention because both buildings were owned by the same person, whose tenants reported that she’d threatened them. The arson squad at the Hudson County prosecutor’s office, which was then run by Harold Ruvoldt Jr., prepared several cases to present to a grand jury, but without enough evidence for anyone to be indicted. (Ruvoldt died as this story went to press.)

“We aggressively did everything we could to find the person who struck the match” in several cases, Ruvoldt said in a telephone interview conducted in May. “We were never able to make that critical connection.”

Across the country, only about 20 percent of all arson cases are ever resolved, with the arsonist identified and convicted. There is no statute of limitations for murder, so fatal arsons are never closed. In Hoboken, 28 remain open.

In the Pinter Hotel fire, Ruvoldt said, investigators checked conflicting evidence: there had been a violent argument that night, some kind of accelerant had been present, there were signs of an electrical short. Nothing was conclusive. “Prosecutors and police are bound by some fairly strict standards of evidence,” Ruvoldt said. “It’s not enough to prove you profited from a fire that caused the death of people.”

Without offering additional evidence or acknowledging the lack of proof, the museum’s exhibit repeats as fact the same arson-for-profit account that has hung over the city for decades.

“I don’t have any,” López said when I asked him about proof. “But what I do have is testimony.” Survivors told him their landlords had threatened to torch their buildings to get them out. But sometimes, inconvenient facts get left out of the narrative. On the day of the Pinter Hotel fire, tenants reported that they had smelled kerosene, and investigators found a suspicious 5-gallon metal can. But later that same day, a state police lab test showed no sign of kerosene, and fire officials said the can was likely used for garbage.

The exhibit preceded another conflict over the same local history. In March, a documentary play by Hoboken playwright Joseph Gallo, Yuppies Invade My House at Dinnertime, premiered. Gallo, the playwright-in-residence at Hoboken’s Mile Square Theater, says his piece was inspired by a 1987 book of the same name that spotlighted the clash between old-timers and young professionals in Hoboken.

In his play, Gallo links gentrification to the fires and says the city has tried to forget they ever happened. “Hoboken clearly is a community that does not know its story,” Gallo, as narrator of his own play, says early on in the staged readings. He then explains that he took on the task of telling that story by interviewing people who had lived through the fires.

Among them was Joe Barry, a critical figure in Hoboken’s revival. His company, Applied Housing, rehabbed about 1,500 worn-out apartments in the city, then rented many to the same people who had lived there before at subsidized rates. Applied later built high-end housing. Barry also started a string of newspapers, including the Hoboken Reporter, which published many of the letters that became the book Gallo used in his play.

“I thought it was going to be some kind of a comedy,” Barry said a few weeks after he attended a performance. In the first act, the horrors of the fires are recounted by four actors as they denounce the money-hungry landlords burning people out of their homes.

Barry, sitting in the audience, could not contain himself. “That’s bullshit,” he muttered, loud enough to be heard on stage. “It’s all lies.”

During an interview, Barry—who was not accused of any arson—argued that it is unfair, even slanderous, to say without proof that landlords, many of them small owners in Hoboken, willingly committed arson, and by extension murder, in order to turn a profit.

Barry says he told Gallo just that, and some of what he said ended up being used in the play, but not the way he intended. He says he watched as Gallo repeated those comments and then, in apparent disgust, threw down his copy of the Yuppies book, which lists Barry as one of the authors.

“He said, ‘Joe Barry says,’ like I was defending the arsonists,” Barry recounts. “So that really infuriated me. And what I really wanted to do was go up and slap him in the face really hard. I wasn’t going to beat him up. I just wanted to slap him in the face and then say something to the people. I never got there.”

He rushed onto the stage but was restrained before he reached Gallo, and then escorted from the theater.

Barry is a major benefactor of the Hoboken Historical Museum, which has a 100-year lease on its space in the old Bethlehem Steel Shipyard that Barry’s company redeveloped. Now 83, Barry says that he originally supported the idea of taking a hard look at the fires when the museum proposed it, but was wary of how the narrative would be presented.

Some other developers and former city officials who had served at the time of the fires also privately objected to the exhibit and the play, but it has become so controversial to even question the standard version of Hoboken’s history that they are reluctant to do so. But for Barry, the demonization of landlords is an attack on his legacy.

A lawyer by training, he started Applied Housing with his father, Walter, to take advantage of federal housing and redevelopment programs begun in the 1970s. He continues to work in Hoboken, although Applied devolved into new companies with different names after he was convicted of making payments to a Hudson County executive who had supported grants for the shipyard project. He was sentenced to 25 months in a federal penitentiary in Maryland.

Barry believes that many fires resulted from poor maintenance and aging electrical and heating systems, not arson. He insists there was no conspiracy to drive the poor out of Hoboken; the market did that as Hoboken drew in people willing to pay more. In his view, every one of those newcomers shares some degree of responsibility for the darker consequences of the city’s metamorphosis.

In March, a small group of residents, tired of waiting for the city to officially acknowledge this dark chapter, did it themselves, dedicating a plaque to the fire victims that was paid for with private donations. The plaque, at a playground on Willow Avenue, reads, “In memory of our Hoboken neighbors who died in the intentional fires of 1978-1983, and the thousands who were displaced and all who bear emotional and physical scars.”

The Rev. Dr. Elaine Ellis Thomas is an organizer of the Hoboken Fire Victims Memorial Project. Photo: Laura Moss

The Rev. Dr. Elaine Ellis Thomas, one of the organizers, says the plaque isn’t at any of the fire sites because they are privately owned. The playground was considered a suitable substitute because it is named for the late tenants’ rights advocate Teofilo Olivieri.

The droopy branches of locust trees growing in Olivieri Park now shade the plaque. One warm May afternoon, I surveyed passersby and found that most hadn’t seen the plaque or known what it was about. But when I read the words to 19-year-old Damian Santiago, his eyes grew wide.

“Whoa,” he said. “Intentional, that’s means on purpose, right?”

Santiago grew up on that same block, in an apartment that his parents rented from Applied Housing, but he had never heard about the fires. “Most definitely it’s a good thing,” to have a plaque there, he said.

A few minutes later, Brennan Hagale entered the park with her two-year-old son, Sullivan, all curls and post-nap energy. While he climbed the playground equipment, she said she was only vaguely familiar with the history the plaque referred to.

She and her husband moved to Hoboken about nine years ago, long after the rash of fires. She worked in production at ABC News, and her husband is a financial consultant. Together, they are a model of the young professionals who have propelled Hoboken’s gentrification. When I told her what Barry had said about newcomers driving the darker side of gentrification, she agreed. “I guess we’re all guilty, in a way, if we live in the new condo buildings,” she said.

She planned to take in the museum exhibit to better understand what the plaque means to Hoboken. “It’s incredibly important to know the history of the town you call home,” she said.

Whoever’s version of its history that may be.

Anthony DePalma, a former New York Times journalist and author of several books, has been contributing to New Jersey Monthly since 1978.

No one knows New Jersey like we do. Sign up for one of our free newsletters here. Want a print magazine mailed to you? Purchase an issue from our online store.