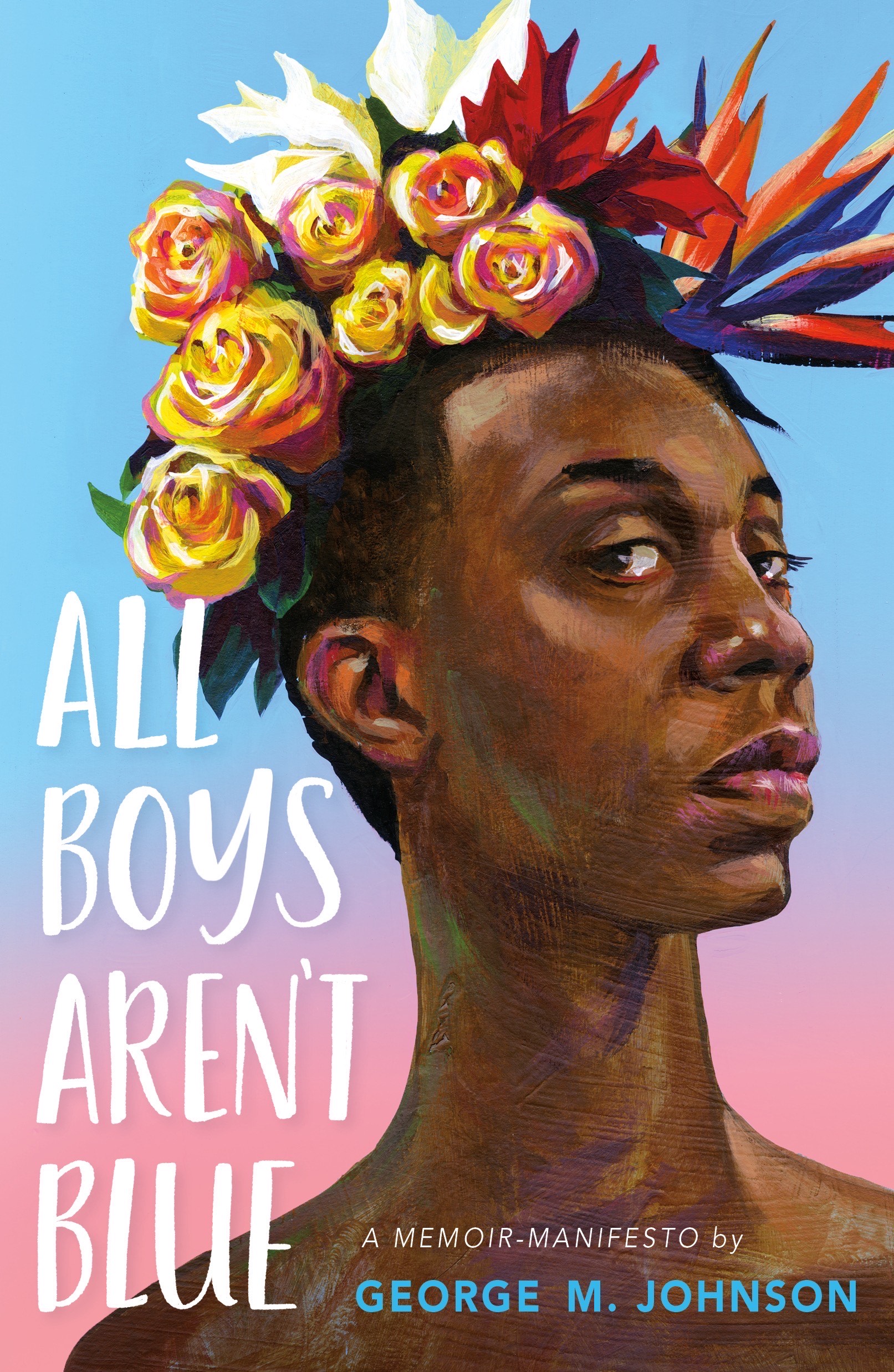

Plainfield native George M. Johnson is one of the most banned authors in the country. Photo: Courtesy of Macmillan Publishers

The critically acclaimed author of one of the most banned books in the country, All Boys Aren’t Blue, George M. Johnson grew up in Plainfield and lived in New Jersey for many years.

Recently, there has been a dramatic increase in the number of books being banned or challenged in school districts across the country, including here in New Jersey. All Boys Aren’t Blue is a story about growing up Black and queer in New Jersey and Virginia.

Johnson, 37, is also the author of We Are Not Broken and has two more books coming out soon. The author (who uses they/them pronouns) recently moved to Los Angeles.

Johnson’s All Boys Aren’t Blue was published in 2020.

How did your upbringing in New Jersey help shape you as a writer?

I grew up in Plainfield, and my entire family for the most part is still there. We had this very tight family dynamic that my grandmother instilled in all of us. I grew up knowing I was a little different, just because I was effeminate, and I didn’t feel like every other boy. But no one in my family ever shunned me for that. I was always included; I was always protected. I think because I got to grow up in that type of upbringing, it allowed me the space to be myself and to kind of grow into the person that I wanted to become, and not the one that society was trying to force me to be. And I think that because of all of that, it gave me the freedom to be a writer and to tell my story and other people’s stories. Writing is a form of liberation in many ways. And so as a person who was often fighting against these systems that tried to oppress who I naturally was, writing was how I was able to fight against it.

[RELATED: Jersey Towns Battle It Out Over Book Bans]

Why do you think that queer Black voices have been so threatening to some people in this country?

It’s interesting because it’s not like our voices are something new. If you look back to the Harlem Renaissance, there were multiple Black voices then, and if we look at James Baldwin or Nikki Giovanni or Angela Davis, there have been people who were Black and part of a non-heterosexual community who have always been at the forefront of writing and thought and being critical of the systems at play in this country. What I think is happening now is there’s this fear that because we are more visible now, it is making the youth choose to be like us. But what’s actually happening is that because we’re more visible now, other people feel safer to be visible, too—people who have always been like us. And now we don’t feel like we have to hide in the ways we did during Stonewall or during the Harlem Renaissance or during other periods in this country. And I think that’s really what the greatest fear is—that the more space we allow for people who don’t fit into society’s mold of hetero norms, [… the more space it allows] for other people who [didn’t always publicly identify in ways that they actually wanted to].

Why do you think there’s been such a dramatic increase in the number of books being banned in the United States?

It’s interesting because sometimes I’m caught between: Is it an intentional thing? Or is it just, like, We ran out of ideas, so let’s ban books? One question I’ve been asking a lot of these people who want to ban books is: What’s the difference between a 17-year-old in high school and a 17-year-old or an 18-year-old in college reading these books? When they go to college, they can read whatever they want. So, what is the difference? What is that one year difference making besides the fact that it’s blocking important information that they need so that they can be better in college? There’s a direct correlation between the rise in sexual assault and rape on college campuses, and the fact that the materials that discuss rape and assault in high school to try to teach kids about consent are being blocked.

I think that there is a fear that they have of Generation Z, that is now starting to become very clear after the last couple of votes have happened. Generation Z has very quickly become the largest voting bloc, and they are young adults who love reading YA books like mine, that open them up to worlds of other people—because books are bridges that build empathy for others. And so what happens is: Gen Z will become the next leaders at some point, but if they go into their leadership already knowing trans people, knowing Black people, then when they’re making decisions and building this country the way they want to build it, they will want to make sure that they are supporting people that don’t [necessarily] look like them. I think that’s really what the fear is—that our books help them to understand the lived experience of people who don’t look like them, and that it makes them want to change.

Do you think that banning books makes young people want to read them more?

Yes! It’s human nature. When I talk with teens, I find that my book is not their first introduction into things that are sexually explicit. I always think about my own experience. By the time I was 10, I knew what pornography was. When I was 13, the Monica Lewinsky and Bill Clinton case was the biggest story in the country. There was no way you could shield us from not knowing what happened between them. I always find it funny that [critics] say these books are sexual. I’m like, this country is [sexual]. The former president [was] literally indicted [over alleged hush-money payments to] a porn star. [People] just think [their] teens don’t see what actually is happening around them when it comes to sex. […] Sex is all around them.

Can you talk about the efforts in Glen Ridge to ban your book and others?

It was so close to home … and it was one of those moments where I had to sit with myself, because I would [have thought] that, at least in my own state, I wouldn’t have to deal with this. When it came time for the meeting, I knew I couldn’t make it, but I knew my mom and my aunts could go. We didn’t know it was going to be that big. [A thousand people showed up.] For me, it was about defending my book and defending the other books, and standing up for somebody who grew up in this state. When I was a teenager, I didn’t have access to this stuff. And so I created these books for the person that I was back then, who deserved to be able to read this stuff. I needed to stand up for 15-year-old me who didn’t have a voice back then. I went to Catholic high school, so I already know my book can’t be read there. This was me fighting for that person who deserved to have this type of book and this type of resource when I was growing up.

It was six people in Glen Ridge trying to remove seven books. I don’t even think they had kids in the [schools]. What’s also been interesting with this fight is that people from other places have been coming into other counties to ban books. There was an 11-year-old who spoke [at the Glen Ridge meeting], who identifies as bisexual, and he said, “I’ve been forced to read heterosexual books my whole life and they’re not turning me heterosexual. So, reading books are not going to turn your straight kids gay,” and everybody erupted into applause. Because that’s really at the heart of it. I was forced to read heterosexual books my whole life. We all have been, but you still see LGBT people exist, and the only type of books we were forced to read weren’t about us.

You were named Honorary Chair for Banned Books Week 2022. Can you talk about how censorship can harm young people? What can be done to inform people about it?

Censorship harms young people because it places them into a world without any knowledge, resources or capacity to navigate the actual world they’re going to live in. When you censor Black books, Latinx books, or books by indigenous people, the child then leaves school with only one frame of reference. When they get to college and they see people of different cultures and they’re like, I don’t understand this culture. Why do y’all do this? It’s because [of censorship], and that’s when the irrational fear starts to build up. That’s what censorship does: It creates irrational fears in young adults because it doesn’t expose them to the real world that they’re going to live in. It’s also interesting that they’re not censoring TV, or social media. The same things that I talk about in my books are on TikTok and other places. And so these young people are still getting the information, and I think we can see why they’re marching and they’re walking out of school [in response to book bans].

The best way to keep people informed is to make sure there are other access points where people can get this information, such as libraries.

Some of the books that have been banned in the past and present are surprising, such as Charlotte’s Web, The Color Purple and Fahrenheit 451. What are your thoughts about that? When does it end?

And where does it start? Some [banned] book lists have 800 books on them. There’s no way that [the people wanting to ban them] have read all 800 of these books. That’s why I keep saying it’s nefarious, because they don’t really know what it is they’re trying to ban. The Diary of Anne Frank gets caught up in there, and you have to wonder why people shouldn’t know about Nazism and World War II? It’s a part of world history. You remove Charlotte’s Web, and you remove Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, and you remove my book … then which books do they actually want kids to read? And, of course, it was the Nazis who also banned books, right? Which was [an early] sign of fascism.

We are in a moment where people are tired of always having to answer to the smallest group of people that are affecting all of our lives. That’s what I learned with the Glen Ridge situation, where 500 people had to show up because a few people had issues with our books. That’s why we have to fight book bans.

Do you ever have young readers come to you and say that reading your book did something important for them?

Yes, I’ve had several young people who have said that reading my book saved their life. I’ve had people who publicly have changed their name because of the chapter that I wrote about the fact that you have the right to change your name if you don’t like it. One teen said that after he read my book, he named his sexual abuser. I get messages about how people say they feel seen for the first time, and they feel heard, and how having the book makes them feel like they also have a space in this world. It’s been really beautiful to witness that.

I’ve also heard from people who say my books help them build empathy for their friends. There have been heterosexual Black boys who have read the book and had questions about navigating the world as a Black person. And so it has a universal tone to it that allows all young adults to be able to get invested in it.

No one knows New Jersey like we do. Sign up for one of our free newsletters here. Want a print magazine mailed to you? Purchase an issue from our online store.