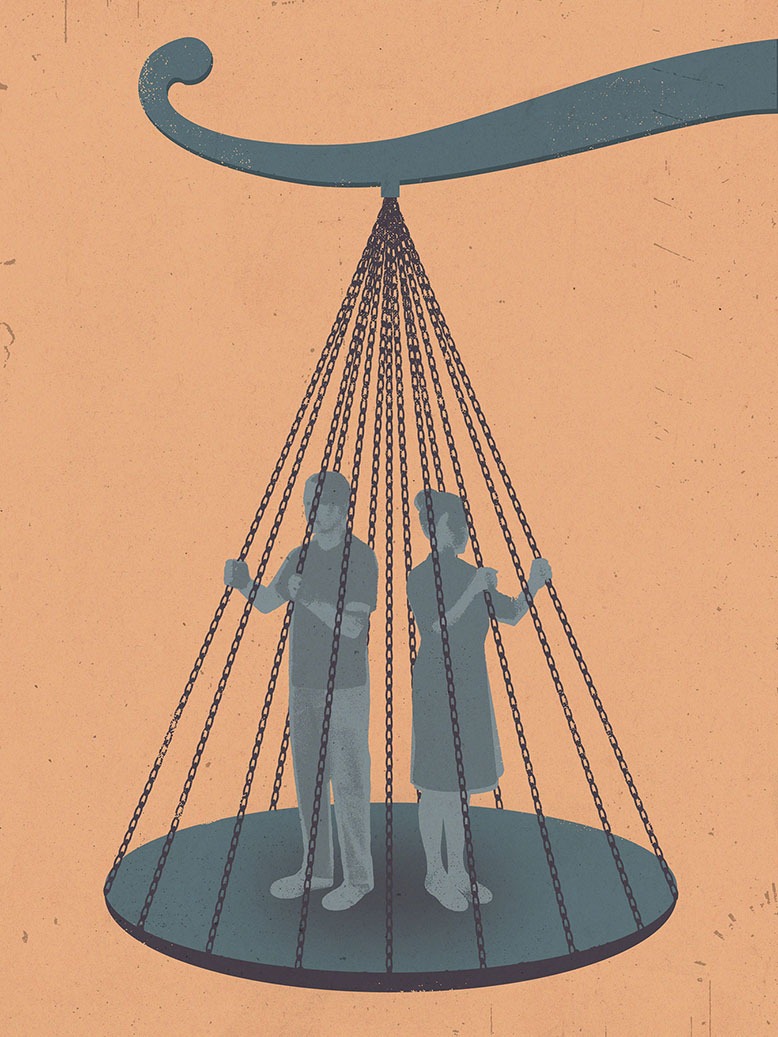

Illustration: Richard Mia

A 72-year-old woman caught in a nasty divorce case waits six years for a judge to end her marriage. A man seeking to wrest custody of his son from an abusive mother has to wait seven years for a court decision.

A kindergartener who splits her time between divorcing parents can’t enroll in a nearby school because no judge has decided her living arrangements.

All of these people are real victims of a New Jersey civil-case backlog that has kept some 9,000 divorce cases and thousands of other civil trials in limbo as the state’s courts—now four years into a critical shortage of judges—slog through a slow-motion crisis that has forestalled justice for thousands.

Frustrated attorneys in these cases say the crisis has visited needless hardship on families across New Jersey.

In some counties, unhappy couples seeking divorce in contested cases are forced to wait three to five years for a trial date. Children caught in custody battles find their lives upended as parents wait months for hearings or enforcement orders. Lawyers making routine motions in personal-injury cases can’t get timely rulings.

As the situation worsened in early 2023, New Jersey Supreme Court Chief Justice Stuart Rabner took the unusual step of suspending matrimonial and other civil cases in six counties so that the stressed-out bench could focus on criminal matters. Family lawyers representing clients in Hunterdon, Somerset, Warren and three South Jersey counties suddenly found themselves with no venue to press claims.

“It’s like living in a third-world country,’’ says Timothy McGoughran, president of the New Jersey State Bar Association. “As U.S. citizens, we’re supposed to be guaranteed our day in court, but that apparently isn’t true in New Jersey.”

According to recent tallies provided by the state, there are now more than 51,000 civil cases backlogged in New Jersey, a logjam fueled by the retirement of more than 300 Superior Court judges in the past decade. More than 50 judgeships, on a statewide bench that when fully stocked numbers about 400, now sit unoccupied.

The great judicial exodus was exacerbated by the pandemic, which stalled in-person hearings and decimated court administrative staff.

McGoughran and other leading members of the New Jersey State Bar Association, however, are quick to point out that state civil courts were constipated long before the pandemic and the recent wave of retirements. Many say the real culprit is a broken system that allows state senators to block judicial nominations indefinitely.

“What’s going on? I’ll tell you what’s going on—political gamesmanship in Trenton,” says Carolyn N. Daly, a family-law attorney in Newark who serves on the New Jersey State Bar Association’s Family Law Executive Committee. “The state Senate sits on nominations for months at a time. It’s beyond political. It’s inhumane.’’

Daly says that much of her time is now spent working with clients whose lives are hung up in the gears of a court system that just doesn’t work.

In every county, she says, unhappy couples who want to be divorced but can’t get a trial are living together under the same roof because they often can’t afford separate homes. She says that children, stuck living for years in toxic households, are caught in the middle of situations that could turn violent at any moment.

Reviewing her current caseload of frozen matrimonial clients, Daly ticks off the absurdities, including a six-year-old forced to travel two hours a day for kindergarten because parents can’t agree on a new school, and clients evicted and going bankrupt while their assets languish in divorce court.

Increasingly, Daly says, people are ignoring court-ordered custody and matrimonial settlements because they simply believe the court has no teeth. Basic enforcement motions that should be decided in days or weeks can take months, she says.

“People know they can violate custody orders and get away with it,” Daly says. “It’s just chaos.’’

Stephanie Frangos Hagan, who heads a family-law practice in Morristown, says clients in several counties routinely wait three to six years for a court resolution of a contested divorce case. She has one client who filed a custody case in 2016 and has waited seven years for a resolution.

“He watched his kid go through middle school and high school, and still this thing dragged on,’’ Hagan says. “People are losing the basic right to a trial that should be guaranteed to everyone.’’

Hagan worries the crisis has also taken a toll on existing judges, who find themselves sinking deeper despite constantly working overtime. In family court, she says, offices have been chronically understaffed. “The level of burnout is real,” Hagan says.

In another case, the family of a 75-year-old man who died in a nursing-home fire can’t get a court date in their wrongful death suit against the nursing home. They’ve been waiting since 2017.

As New Jersey’s judicial crisis festers, political leaders appear to be doing little.

In most other states, jurists are elected by voters, but in New Jersey judges are nominated by the governor and approved by the Legislature. The Senate Judiciary Committee holds hearings on all nominees.

Over the years, state senators have not been shy about exercising an unwritten privilege known as senatorial courtesy, which enables them to block nominees from their home district indefinitely, for any reason at all.

Senators frequently use the privilege to gain leverage in petty political squabbles. They can also use it as a tool to advance policy. Often, senators withhold approval without even announcing their reasons.

Critics like former state Senator Kevin O’Toole, who worked unsuccessfully to end the privilege, say the opaque practice is antidemocratic. “Ultimately, the political desires of 40 members of the Senate should not outweigh the needs of 8 million New Jerseyans,’’ O’Toole wrote in a 2014 op-ed.

The State Bar Association says several judicial nominees that it has interviewed and approved after full vetting are waiting for a vote in the Legislature.

Neither the governor’s office nor members of the Senate’s majority Democratic office granted requests for an interview about the judicial delays.

Richard McGrath, a spokesman for NJ Senate Democrats, said in November that the Senate had confirmed 71 Superior Court judges during the current legislative term and 155 during the entire six-year administration of Governor Phil Murphy. While both the governor and Legislature moved on 11 bench candidates in December, there was still a shortage of some five dozen judges at the close of 2023.

Chief Justice Rabner, a Harvard Law graduate and former U.S. attorney who is widely considered one of the most distinguished jurists in recent New Jersey history, was himself the target of a senatorial courtesy blockade when he was nominated for the state high court in 2007. He eventually cleared the hurdle and was approved by the entire state Senate in a 36-1 vote.

In May, he used an appearance at the annual State Bar Association convention in Atlantic City to exhort action on the judicial crisis. The bottom line, he reminded everyone in a speech that drew cheers from the audience, is that people are in need.

“Every case has its own story. And every case matters,’’ Rabner said.

“A parent in a contentious divorce is waiting to hear the schedule for when they will be able to spend time with their child. Someone else is battling to protect their constitutional rights…. People come to the court system to seek justice; we must do better as a state to give them the attention that they deserve.’’

Jeff Pillets is an award-winning investigative reporter.

No one knows New Jersey like we do. Sign up for one of our free newsletters here. Want a print magazine mailed to you? Purchase an issue from our online store.