In the late afternoon sunlight of a brilliant day in May, Joseph Mulvanerton knelt beside Timmy Wiltsey’s grave and apologized to a boy he had never met. He reached out and ran his fingers over the gravestone’s cool, marble face. “We really tried, Tim. We really, really tried,’’ said Mulvanerton. “I’m sorry for it all.”

In 1992, police found what was left of 5-year-old Timmy Wiltsey half buried on the banks of Red Root Creek, a stream that drains the swamps and salt marshes along the Raritan River in Edison.

Mulvanerton, an easygoing man in his early 60s who works as an account manager for a New York financial firm, was juror number 2 in the first-degree murder trial of Michelle Lodzinski—little Timmy’s mother.

For 43 days in 2016, Mulvanerton sat in a Middlesex County courtroom and fought back his emotions while prosecutors argued that Lodzinski had killed her son, dumped his body in the swamp, and then concocted an elaborate cover-up to escape detection.

After the jury found Lodzinski guilty of first-degree murder, Mulvanerton went home and sobbed for two hours. “The jurors were just ripped up,’’ he says. “We watched Michelle Lodzinski just sitting there day after day, cold as ice, not showing the slightest bit of emotion, even as they talked about how wild animals had torn up the body of her son.”

“We tried to get it right for Tim. We wanted to give this child some kind of peace, and we walked out of that courtroom feeling a guilty verdict was right.’’

But barely five years after Lodzinski had been sentenced to 30 years in prison, a deeply divided New Jersey Supreme Court overturned her conviction and set her free. Justice Barry Albin, who cast the tie-breaking vote on the seven-member court and wrote the majority opinion, said there wasn’t enough hard evidence showing Lodzinski had actually done it.

The court’s ruling on December 28, 2021, brought an official end to one of the most tortuous criminal-justice sagas in recent New Jersey memory, and ensured that Lodzinski would remain free, under the principle that criminal defendants in America can only be tried once for the same crime. Police say the court’s decision has effectively closed off further investigation into Lodzinski, the only serious suspect, and precluded the hunt for DNA evidence or other physical evidence.

But more than a year and a half after Lodzinski’s conviction was overturned, people who were involved in the case are still coming to terms with the reality that there may never be justice for Timothy Wiltsey, who would have turned 38 years old this month.

They still recall every jarring fact about the little boy’s disappearance, the discovery of his body, the bizarre behavior and fabrications of Lodzinski as police pursued her, the stalled investigation and two decades of cold-case limbo, the eventual prosecution and conviction, and the stunning reversal.

New Jersey Monthly is revisiting the case to tell those people’s stories. They say they have decided to speak in fresh detail now in order to help bring closure and to commemorate the lost boy.

“It was the case of our lifetime,’’ says James Ryan, the deputy police chief of South Brunswick.

On May 25, 1991, Ryan was just 22 years old and working as a member of the rescue squad in South Amboy, the Middlesex County town where he was born and raised. About 7:30 pm, a call came in about a young boy who had gone missing from the Elks Club carnival at Kennedy Park in Sayreville.

Timmy, a kindergarten student at St. Mary’s Elementary School, had been wearing red shorts, a red tank top and his favorite Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles sneakers. Lodzinski told police she’d brought her son to the park around 7 pm, put him on three rides, and then left him by himself—for just a moment—while she went to buy a soda. “I turned around and he was gone,’’ Lodzinksi told police.

The carnival shut down as officials scoured the grounds. By dawn, hundreds of volunteers had spread out around the carnival site, surrounding woods and fields. A scuba team got involved. Searchers trolled the town’s bayfront and playgrounds around the duplex apartment where Lodzinski, a single mother, lived with her son. Within 24 hours, the New Jersey State Police and FBI had joined the hunt.

“If we didn’t find Timmy right away, the chances of ever finding him would go down dramatically,’’ Ryan tells New Jersey Monthly. “I think everyone in the whole town knew these hours were critical.’’

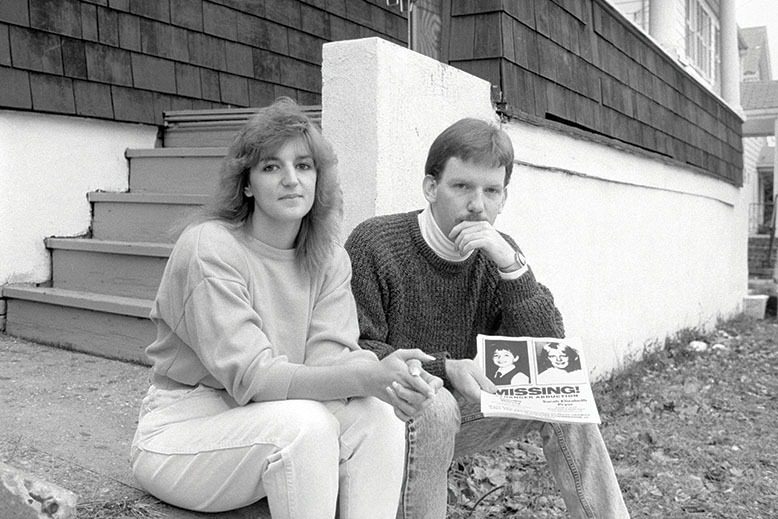

Before cell phones and social media, getting word out about a missing child was a challenge. Ryan didn’t even have access to a working copy machine that Sunday, the day before Memorial Day, so he asked local businesses to print fliers.

Within days, news of Timmy’s disappearance had aired on TV news across the region. His picture was printed on milk cartons. Ryan and teachers at Timmy’s school began raising money for a campaign designed to keep the boy’s name out there. But weeks passed with no news.

Five months later, a high school chemistry teacher with an interest in birdwatching was tramping through wetlands behind the Raritan Center industrial park in Edison when he stumbled on a Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles sneaker in the mud. Daniel O’Malley had heard about Timmy’s disappearance and turned the shoe in to the police.

The discovery turned out to be the key to finding Timmy’s remains.

“I’d like to think our efforts to keep the public looking for clues had some part in the discovery of that shoe,’’ Ryan says. “I only know we kept trying; we kept hoping that some kind of answer would show up.’’

***

About three weeks after Timmy disappeared, Lodzinski sat for an interview with New Jersey State Police lieutenant Jerry Lewis. Now retired, Lewis was, even at that early stage of his career, considered perhaps New Jersey’s most effective detector of lies.

Like many in law enforcement, Lewis was trained in the use of the polygraph. He was supervisor of the state’s polygraph unit for many years. But his signature skill lay in the obscure discipline known as statement analysis, which, as Lewis explains, is a kind of deep listening that can reveal clues hidden in the words of a suspect. Lewis has conducted more than 4,000 criminal examinations and extracted dozens of confessions, even in homicide cases. He has taught his techniques to more than 30,000 professionals.

By the time Lodzinski sat down with Lewis, she was already the prime suspect. She had changed her story several times. Initially, she said, Timmy had simply vanished. At another point, she claimed another person had been involved, a mysterious go-go girl named Ellen. Her latest story involved a claim that Timmy had been snatched by a man with a knife.

Police never found Ellen. But they built a thick file on 23-year-old Lodzinski, who was financially stressed and sometimes stayed out all night, leaving Timmy with babysitters. Timmy had missed school more than 20 days that year and been recorded late for class more than 60 times.

“When I entered the picture, they had their suspect, but they didn’t have a confession and they didn’t have a body,’’ Lewis told New Jersey Monthly in May.

At the outset of an interview that stretched more than five hours, Lodzinski uttered words Lewis found revealing. She repeated the words several times: “I would never hurt my son.’’ The suspect’s careful and repeated choice of the same words, Lewis says, signaled she knew the truth about Timmy’s disappearance.

“Nobody wants to see themselves as a criminal; they want to see themselves as a normal person who made a mistake,’’ Lewis says. “She saw herself as a good mother, and she wanted the world to see that too.’’

Lewis asked Lodzinski to remember all she could about the man who she claimed had held a knife to Timmy in woods near the carnival. Lodzinski, he says, drew a picture of the knife and described the woods as a place next to an abandoned building. He then asked her, “Where exactly are these woods?’’ Lewis says his question was followed by a long silence where Lodzinski slumped and looked at the floor. “She was in the classic confession pose,’’ Lewis says.

It was then that a police officer who was also in the interview room broke the silence in a fit of anger: “Jerry, she’s a liar and she killed her kid!’’ The outburst, Lewis says, broke off the interview.

Neither Lodzinski nor her lawyer responded to requests to be interviewed for this story.

***

Despite the publicity surrounding Timmy’s disappearance and the mass of circumstantial evidence, prosecutors decided in 1992 that there was simply not enough to charge Lodzinski.

Twenty years passed. In the interim, Lodzinski had moved to Florida, gotten married, and had two more boys. Then, in 2011, the Middlesex County prosecutor’s office revived the case in a general review of cold cases. In the evidence locker was a blue blanket that had been found near Timmy’s remains. Lodzinski said she didn’t recognize it, and forensic tests did not yield clues that could tie it to her.

The prosecutors then took a simple step they had not taken in 1992 when the blanket was found: They showed it to one of Timmy’s babysitters, who immediately recognized it as the boy’s favorite blanket. Another sitter described snuggling with the boy under it.

Wielding the blanket and new testimony, prosecutors arrested Lodzinski on August 6, 2014—the day Timmy would have turned 29. Two years later, Lodzinski was convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to 30 years without the possibility of parole.

Gerald Krovatin, Lodzinski’s lawyer, argued that it would be a miscarriage of justice to convict her without physical evidence proving where and why she had killed Timmy. Six years later, a majority of the state Supreme Court agreed.

For Joseph Mulvanerton, the overturning of Lodzinki’s conviction reawakened his feelings in the jury box. Once again, he could see the graphic images and see Timmy’s mother sitting there.

Standing over Timmy’s gravestone at St. Joseph’s Cemetery in Keyport this past May, he picked up toy cars someone had placed on the grave along with flowers. Someone had also left behind a smiling Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles toy.

“Well, Lodzinski got her appeal,” Mulvanerton said. “But where’s my appeal? Where’s Timmy’s appeal?’’

Jeff Pillets is an award-winning investigative reporter.

No one knows New Jersey like we do. Sign up for one of our free newsletters here. Want a print magazine mailed to you? Purchase an issue from our online store.