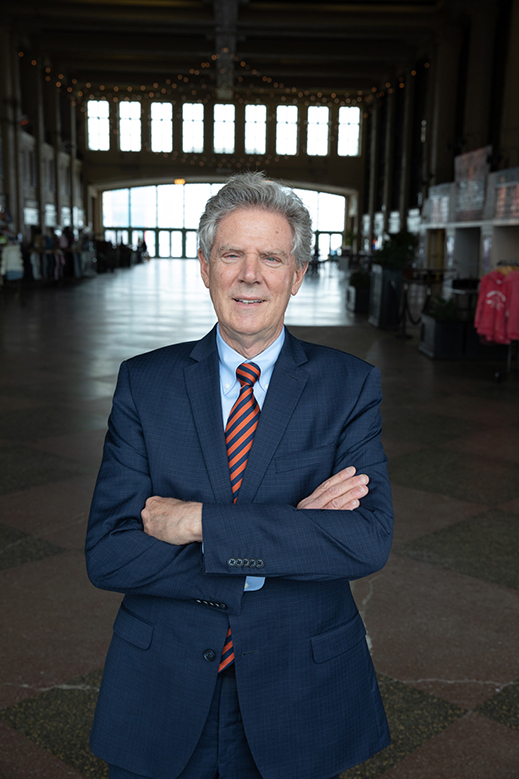

Lifelong Long Branch resident Frank Pallone Jr., seen here in Asbury Park Convention Hall, has been re-elected 16 times to represent the Shore area. Photo by Allison Michael Orenstein

Frank Pallone Jr. is, first and foremost, the congressman from the Jersey Shore. To drive home that point, his name shows up in the news every year as the guy who helps replenish the sand on our beaches—an estimated total of 163 million cubic yards of the stuff over the last three decades, at a cost of $1.2 billion to the federal government.

The lifelong Long Branch resident has served since 1988 in the House of Representatives, and has been chairman of the powerful Energy and Commerce Committee since the Democratic Party took back control of the House last year.

When the House is in session, he spends four to five days each week in Washington, D.C. When he’s not in the nation’s capital, Pallone, like most members of Congress, comes home to be with his family and to spend time with constituents.

On one recent spring day, Pallone met with the father-and-son management team at Foley Cat, a family-owned franchise operation in Piscataway that sells and services heavy equipment. He toured the facility, then headed to a meeting with the Middlesex–Somerset County AFL-CIO Central Labor Council at their union hall in Sayreville. The union guys mostly complained about a lack of respect from the Trump administration and the president’s lack of an infrastructure plan.

Next came an emotional meeting in Pallone’s New Brunswick office with two Salvadoran women, Asbury Park residents who have been in this country for more than two decades but who face deportation in January when the Temporary Protected Status program expires.

Pallone supports the program, but offered little hope that the Trump administration will extend the status of the two women, even though one of them is an entrepreneur and both regularly pay their taxes. If deported, one of the women will have to decide whether to bring her 13-year-old daughter, who was born here and is a citizen, back to El Salvador.

Pallone can’t solve every constituent problem that comes his way, but his new chairmanship does provide significant influence. His committee has jurisdiction over health care, including Medicare and Medicaid; consumer protection, including food and drug safety; energy policy, the environment and climate change; and telecommunications and the Internet. That means about 40 percent of all bills introduced in the House are referred to Pallone’s committee for hearings. The committee also oversees five cabinet departments and seven independent agencies. The committee’s scope is so vast that the late John Dingell, a Michigan Democrat and a former Energy and Commerce chairman, has been quoted defining the committee’s reach with the quip that, “If it moves, it’s energy, and if it doesn’t, it’s commerce.”

Pallone’s stature makes him a power back home, too. After Superstorm Sandy, he pressured insurance companies to meet their obligations and sponsored federal legislation to reform the flood insurance program. More recently, he introduced a bill in the House that would provide grants to pay part of the cost of removing toxic chemicals from New Jersey’s drinking water.

On another front, Pallone and his 11 New Jersey colleagues in the House co-signed a letter encouraging the Interior Department to abandon plans to allow companies to drill for oil and natural gas off the Jersey Shore. “There’s only about two weeks supply of oil out there,” he says. “There may be more, but it’s just not worth it. The risk is that you have a spill and you destroy the whole tourism industry.”

Pallone’s committee, it sometimes appears, is the only House panel not preoccupied with investigating President Trump. Instead, he has pursued an ambitious agenda that often has the committee’s staff scurrying. In just the first few months of his chairmanship, he steered measures through his committee and the full House on net neutrality, health care affordability and prescription-drug pricing, as well as a bill to keep America in the Paris Climate Agreement. Things don’t usually happen that quickly in Congress.

The bills passed in the House, but have little chance of becoming law as long as the Senate has a Republican majority and Donald Trump is president. Pallone remains undaunted. He’s establishing a traditional Democratic agenda for the day when, he hopes, Democrats once again control both houses of Congress and the White House. And even as the young progressives in his own party are making their voices heard, the pragmatic Pallone is more interested in preserving Obamacare and existing environmental regulations than in pursuing goals that he sees as not only divisive, but potentially politically dangerous for Democrats.

The preservation of Obamacare is something of a legacy issue for Pallone. He was chairman of the Health Subcommittee when the Affordable Care Act became law in 2010. But he also sees little benefit in handing the Republicans a cudgel they can use to beat Democrats in moderate House districts in 2020. He predicts that, if his party adopts the pet projects of the new progressive members, “Republicans will say, ‘Let’s just talk about Medicare for All and the Green New Deal,’ so they can beat us up with them.”

Pallone’s current agenda didn’t end with passage of his initial package of bills. In response to an Environmental Protection Agency ruling to allow the use of asbestos in some manufacturing, he introduced a bill that made it clear that “anything less than a full ban is unacceptable.” Proposing new laws isn’t the only tool at his disposal. He also reached out to Facebook executives for an explanation about why it was exposing health information, including substance abuse, about some Facebook customers. Committee members later followed up with a meeting with Facebook.

Pallone has a secret weapon for getting things done. Unlike many other New Jersey political figures, he is neither confrontational nor obsequious. People like him instantly, and he rarely does anything to alter that initial impression.

The son of a policeman in Long Branch, where the congressman’s brother John was elected mayor in 2018, Pallone earned degrees from Middlebury College, the Fletcher School at Tufts University and Rutgers-Camden Law School. He practiced maritime law and was elected to the Long Branch City Council in 1982, at the age of 30, and to the New Jersey State Senate in 1983. When Congressman James Howard died suddenly in 1988, Pallone won his seat in a special election. He has been reelected to 16 full terms since then. “I actually enjoy campaigning,” he admits. A bachelor when he was first elected, Pallone married Sarah Hospodor, a Jersey native, in 1992; they have three grown children.

The district Pallone inherited included Shore communities in Monmouth and Ocean counties. Three redistrictings have pushed his constituency northward and inland. As a result, his district shed Republican-leaning Ocean County and gained more Democratic Middlesex County.

The geographical shift made Pallone’s elections easier. Since 1994, he has earned at least 60 percent of the vote in all but five elections.

Still, he is not immune to constituent complaints. When he met with Kim and Jamie Foley, chairman and CEO, respectively, of Foley Cat, and the AFL-CIO leaders in Sayreville, they all wanted to know why Democrats and Republicans in Washington can’t stop fighting and pass an infrastructure bill that would benefit both business and labor.

Pallone doesn’t blame congressional Republicans for the inaction. “We get along better than people imagine,” he says. “We socialize more than people think.”

The blame for capital gridlock, he says, rests squarely with President Trump. “You can’t make a deal with him,” says Pallone. “He’ll agree with you one day, then change his mind the next day. You can’t work with that.”

Pallone’s efforts meet with almost universal praise. Business leaders laud him. Rich Weeks, the CEO of Cranford-based Weeks Marine, Inc., one of the nation’s largest dredging companies, first met Pallone at state Senate hearings in the 1980s, when both worked to clean the beaches of medical waste. Weeks says that, while he and Pallone “don’t always agree, he’s a good listener, and we talk all the time.”

Advocacy-group leaders have a similar response. Cindy Zipf, executive director of Long Branch-based Clean Ocean Action, also goes back with Pallone to the 1980s. She calls him “a champion of the marine environment, not only for New Jersey, but for the entire nation.”

Fellow Democrat Vin Gopal, a state Senator and former Monmouth County Democratic chairman, praises Pallone’s political commitment. “I can’t tell you how many calls I get from him about local issues,” he says. “He is so good at politics because he understands people and is in every end of the district.”

Union County lawyer Frank Capece is even more fulsome with his assessment. “Pallone feels no need to tell everybody he’s the smartest guy in the room,” says Capece, “even though he usually is.”

After 30 years on the job, Pallone is unlikely to develop an overinflated ego, and he’s even less likely to forget the importance of the sand. As long as New Jersey has beaches, Pallone will see to it that the Army Corps of Engineers keeps the sand coming. And the press will be there to make sure everybody knows who made it happen.