Zina Williams tunes out the radio playing overhead as she carefully reads the prescription, whispering the ingredients to herself. She turns to the shelves with their bottles of powders and liquids arrayed alphabetically and locates the two ingredients she needs: hydrocodone, an opioid, and Avicel, a filler.

Williams, a pharmacy technician at Liberty Drug and Surgical in Chatham, is doing what few pharmacies do these days: She is compounding a prescription medicine from scratch.

“This is for pain,” she says as she gathers the materials needed to make 90 capsules, as indicated on the script. “It’s for intractable pain… pain that doesn’t go away.”

Williams uses a thin spatula to scoop the hydrocodone out of its bottle, carefully placing the white powder on a digital scale, tapping the tool ever so slightly with her index finger so that the medicine falls like snow into a neat pile. Once the measurement on the digital scale matches the weight called for on the prescription, she repeats the same process on a second scale with the Avicel filler.

After weighing both, Williams calls out “weight check” and another pharmacy technician and a pharmacist double- and triple-check her measurements. Once the weights are confirmed, Williams pours the hydrocodone into a stone mortar and gradually adds the Avicel, stirring the two with a pestle until they form a single powder. Next, she spreads the powder into the slots of a special machine that creates the 90 capsules required for the patient.

Pharmacist Alan Brown, owner of Liberty Drug since 1986, says the compound that Williams has just made could have been prescribed for a number of reasons.

“[The pain] could be from an auto accident, it could be post-surgery pain, it could be after amputation where they have what’s called phantom pain,” he explains. “And the reason we make it is because a lot of the manufactured products contain Tylenol along with the pain medicine, and Tylenol is toxic to the liver…. If you take enough of it for an extended period of time, you’ll get liver toxicity and you’ll die.”

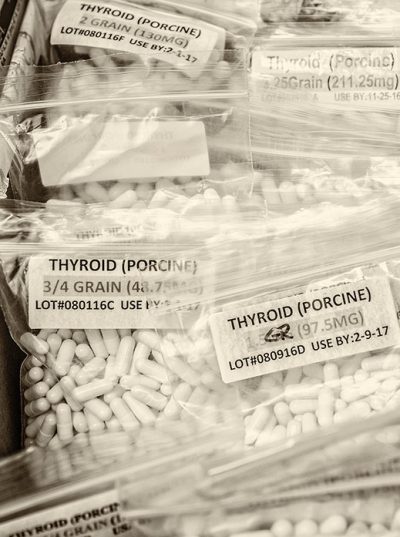

Licensed pharmacists and technicians who specialize in compounding create custom medicines to meet the special needs of human and animal patients. A patient might need a compounded medicine—as opposed to a commercial drug available at most retail pharmacies—for a number of reasons. They might be allergic to or intolerant of a specific ingredient in the common drugs; they might need a specific dosage that is otherwise unavailable; or they might need the drug in a specific form, such as a suppository or ointment.

The pain medication that Williams created took only about 10 minutes to compound. Others can be far more complex, with multiple ingredients or hand-made capsules—even special flavors.

“We make medicine for pets, for physical-therapy patients, for children who have digestive problems, for older people who have hormone-replacement needs,” says Brown. “In virtually every aspect of medicine, there are compounds that can be used, and many times, more successfully than the commercially made products.”

There are approximately 2,185 pharmacies registered with the New Jersey Board of Pharmacy. According to Brown, about 30 offer compounding in a retail setting. (The state could not provide a precise figure.) Eighteen pharmacies are accredited by the Pharmacy Compounding Accreditation Board (PCAB), a nonprofit that develops industry principles, policies and standards for compounding. Such accreditation, however, is not required.

While compounding pharmacies are few, the reasons people seek their services seem quite common.

Parents, says Brown, may request a prescribed medication, like an antibiotic, be compounded in a liquid form with a flavor that their child will tolerate, like tooty fruity, marshmallow or watermelon. Pet owners looking to coax their companions into taking a needed remedy might request specific flavors, like bacon (see story, below). In other cases, a patient may be severely allergic to wheat-based components that are used as binders in many commercial products. A compounder can use a synthetic binder instead.

“We make products with no wheat, no gluten, no flavors, no colors, because there are kids who are allergic to dyes [and] certain fillers; and not only children, but adults,” says Brown. “We customize what we do…. It’s removing the fillers and components and flavors and binders from a lot of the products that are out there.”

Some compounders also specialize in sterile medicines, like eye drops or injectables. This requires different training and equipment in a germ-free lab.

Compounded drugs are of particular importance for hospice and special-needs patients who cannot swallow a capsule or tablet. For these patients, compounders can turn their medicine into a liquid, gel, suppository or a cream that can be absorbed through the skin.

Men and women in need of hormone-replacement drugs are also good candidates for compounding. Because no two bodies are alike, one-size-fits-all commercial drugs may fall short when there is a need to balance unstable hormones. This often requires a unique dosage from a compounder. What’s more, compounders can create medicines with naturally occurring hormones rather than synthetic ones. A type of yam, for example, contains natural levels of estrogen and progesterone that are chemically identical to the hormones found in the human body. Compounders use the yam extract to create a custom medicine for menopausal women.

Compounders can even replicate discontinued medicines. Take Donnatal, a drug used by those with anxiety for upset stomach and others with symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome; manufacturers no longer make a generic version of the medication, but compounders can. Compounders can also produce drugs that temporarily are in short supply in the marketplace—such as Tamiflu, which became scarce in the winter of 2013.

David Miller, a pharmacist who became involved in compounding to accommodate hospice patients in the 1980s, says there has been “tremendous growth” in consumer interest in compounding over the past 15 years. He sees that as a product of the more holistic approach to medicine and a return, in some cases, to the way things were a century ago.

“The pharmacist would get a prescription that would have seven or eight ingredients in Latin, and they would have herbs that they would mix together to make something for patients,” says Miller, who has owned and operated Miller’s Homecare and Compounding Pharmacy in Wyckoff since 1982. “It became kind of a lost art when commercial drug companies, known as ‘big pharma’ collectively, basically took over the entire drug industry.”

Before the days of commercial drug manufacturing, all pharmacists were essentially compounders; they made medicines by hand with a specific patient in mind, mixing elixirs or scraping powders into individual capsules. Miller says he remembers observing his own grandfather, who opened the pharmacy in 1929, making capsules nearly all day long.

When Miller’s parents took over in the late ’50s, mass-produced drugs were just becoming commercially dominant, and the pharmacy eventually carried almost all commercial products. By the time Miller took over in 1982, the pendulum had begun to swing back. He realized compounded medications provided much-needed solutions for the hospice patients he worked with and could be beneficial for a wide range of customers.

While basic compounding is still taught as part of the curriculum in most university pharmacy programs, it takes a good mentor, and a lot of training and practice, to become an effective compounder.

Miller was trained by David Sparks, the former CEO of the Professional Compounding Centers of America (PCCA), a resource for compounders headquartered in Texas. Today, Miller’s Pharmacy is licensed in all 50 states; they ship compounded medications as far away as Hawaii and Alaska.

In New Jersey, all pharmacists and pharmacy technicians must be licensed by the Board of Pharmacy, which falls under the Division of Consumer Affairs. No additional licensing is required of compounders, but Miller says technicians and sterile-compounding pharmacists “require evidence of training and competency.” The state Board of Pharmacy and accreditation bodies will request this evidence of training upon inspection, Miller says, although it is not required for a license to be obtained.

Miller’s pharmacy and many other compounding pharmacies typically have their own in-house training program and tests for new hires. Additionally, technicians learn tricks of the trade on the job under supervision of a licensed pharmacist.

“The technician really never works on their own,” says Brown. “We, the pharmacists, check every ingredient and every weight and every volume that they weigh out before they actually prepare a product. And we have three sets of eyes—a technician who weighs it, a technician who checks that, and the pharmacist who checks that… because three pairs of eyes are better than two.”

In fact, learning on the job is essential in compounding, which requires constant innovation to meet the individual needs of patients.

Brown recently had a patient, a 13-year-old girl, who was diagnosed with Lyme disease. She couldn’t swallow a tablet. In consultation with the girl’s doctor and mother, it was decided that a suppository was the best option.

Other patients require unique solutions. Miller once made a nebulizer for a parrot with a lung infection. The ailing bird’s cage was temporarily covered with a plastic bag and the medication piped in.

“There’s a lot of science in it…. [We’re] constantly innovating,” Miller says. “And the innovation has to, of course, be in the realm of good science.”

Innovation can also help patients avoid side effects. Take a pregnant woman who needs progesterone in order to carry her baby to term. Taken by mouth in capsule form, Miller says, the drug might make her sleepy. Used as a cream absorbed transdermally (through the skin), that side effect can be eliminated.

“We had a patient who had his tonsils out, but he couldn’t swallow any medicine for the pain he was getting. We made the pain medicine into a cream that they rubbed onto the inner wrist,” Brown says. “It works.”

Brown adds that a compounder can combine several medications into one transdermal gel so that the patient does not have to ingest multiple pills on a daily basis.

Often, when new ingredients are used, or if the dosage is critical, the compounding lab will send the final product to be tested for potency and other factors before dispensing it to a patient.

Such testing is essential because, while all drugs used to make a compound are FDA-approved, the compounded drug itself is not.

“The final compound that we make,” explains Miller, “is not an FDA-approved drug because we’ve never gone out and done studies on 100,000 patients and [gotten] a national drug code and gone to the FDA for a particular indication. We’re not allowed to make any medical claims for anything that we do. We’re not marketing a drug out there…. We’re working with a physician to find a solution for a patient. It’s very different.”

While many patients require—or simply prefer—compounded medicine, they may wrestle with their insurance carrier for coverage. “The most common topic of conversation is what my insurance company isn’t covering today,” Miller says.

Even though the prescription is written by a licensed doctor, filled by a licensed pharmacist or pharmacy technician, and all drugs used are FDA-approved, insurance companies often will not cover the full cost. Sometimes, says Miller, the insurer does not see the compounded form as necessary—for example, if a child dislikes the flavor of a commercial product. Other times, the insurer might refuse to cover one of the ingredients in a compound.

That means coverage has to be handled case by case. Miller’s and Liberty Drug work with patients to get coverage or reimbursement from insurance companies. Other compounding pharmacies might require out-of-pocket payment up front.

“We’ve had many cases,” says Brown, “where we’ll say to the patient, ‘The medication is going to be $75,’ and the patient will look at us and say, ‘I can’t pay it.’ And we’ve given them the medicine for free. And you know why? We have a heart. Because I would rather give them the medication for free than deny them medicine.”

Miller and Brown like to talk about the “triangle of care”—physicians, pharmacists and patients—and how they work together to find solutions for patients’ specific needs. “That” says Miller, “is what good compounding is all about.”