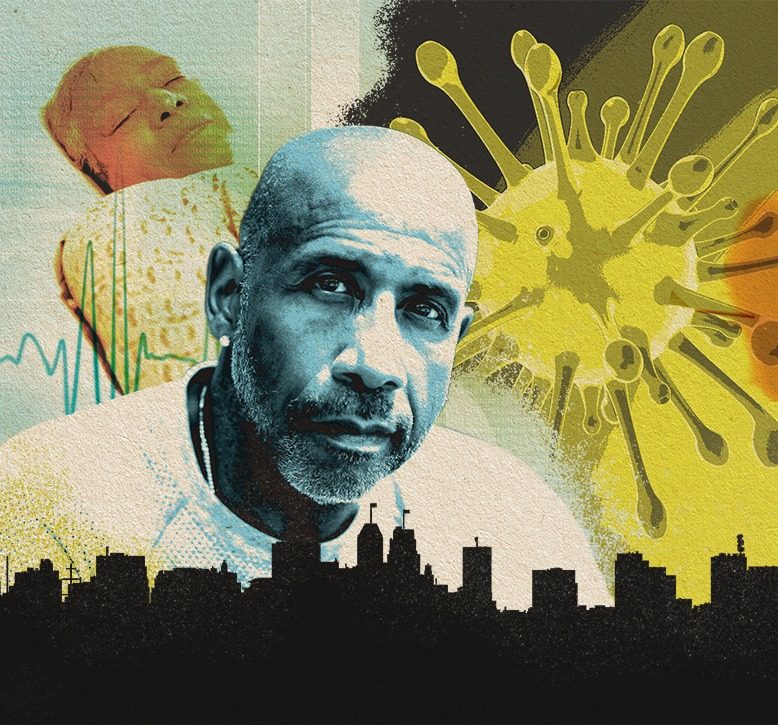

Nationwide, reports have surfaced regarding the disproportionate number of African-Americans dying from Covid-19. For example, as of late April, African-Americans accounted for 70 percent of Covid-19 deaths in Chicago, where they comprise just 30 percent of the population. African-Americans make up 13 percent of New Jersey’s population, but 18.5 percent of virus fatalities, according to state data for early June. Public health officials have seen similar impacts on people of color in Philadelphia, Detroit and other cities.

Experts say that part of the reason for these sad statistics is that people of color—including Latinos—are disproportionately affected by preexisting health conditions. That puts them at greater risk if infected with Covid-19.

But there’s more to the story. According to Michellene Davis, executive VP at RWJBarnabas Health, government laws and policies and local zoning regulations also contribute to health disparities. Davis, a nationally recognized health equity and policy expert, says a major concern is the historic displacement of people of color to inadequate housing in densely populated areas, where economic disinvestment contributes to poorer living conditions, and factory and environmental pollutants compromise air and water quality.

Specifically, says Davis, exposure to environmental hazards and limited access to affordable medical care and nutritious food yield “higher rates of hypertension, heart disease, asthma and diabetes among people of color today.”

And, while it might seem imperative that these high-risk people of color shelter at home during the Covid-19 pandemic, many are not privileged to do so. “Often without personal protective equipment, they are restocking our groceries, driving our buses, making and delivering our food, cleaning and disposing of our trash,” says Davis. If they don’t, she says, “they will not be paid.”

[RELATED: How Covid-19 Rocked Elder-Care Facilities]

Without the ability to shelter at home, these workers—considered essential under state guidelines—often take fever reducers to get through shifts, Davis says. As a result, if and when they finally see a doctor, their body temperature reads lower than the required level for Covid-19 testing.

“This pandemic,” says Davis, “has further highlighted the need for public health leaders to focus on and work to eliminate health disparities by setting equitable policies, practices and recommendations for screening, treatment and training, especially during crises.”

Denise Rodgers, a medical doctor and vice chancellor for interprofessional programs at Rutgers, echoes Davis’s remarks on historic race- and ethnicity-based lifestyle disparities. Rodgers says there’s much to be learned from the current pandemic. “The first lesson is somewhat related to disparities and outcomes in race and ethnicity,” says Rodgers. “We can never allow our public health infrastructure to be as weakened as it was when we were confronted with this pandemic. We have known about health disparities for over 30 years.”

Rodgers acknowledges that the nation has made progress in overcoming these disparities, but says more work is needed. “We need universal access to health care,” says Rodgers, “because a major obstacle to people being able to treat their chronic illnesses, which then would prepare them better to face something like this, is disparate levels of ability to get basic primary care.”

Adds Davis, “Inclusive health, education and economic policies not only will dismantle the effects of structural racism in vulnerable communities, but also will shore up the rest of society.”